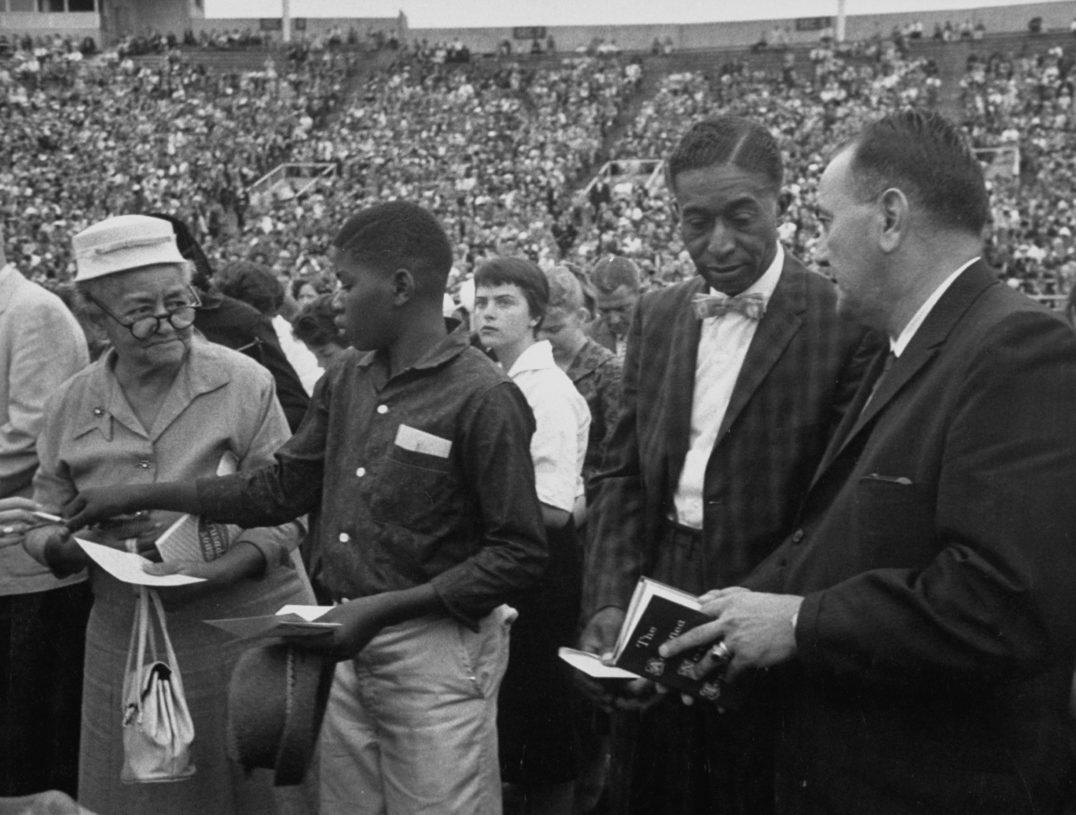

What does it mean to be human? This is the grand anthropological question of Peaceful Science. This excellent article was first published at Sapiens, and authored by Brian Howell, an anthropologist at Wheaton. As segregation ended, the great evangelist Billy Graham contemplated the gospel alongside the anthropology of race: “God hath made of one blood all the nations of the world.” Acts 17:26.

On March 2, millions watched the funeral of the Rev. Billy Graham, one of the most prominent religious figures of the 20th century. His life was influential to many, and anthropology was an influence on him. As an anthropology major at Wheaton College, young Graham encountered ideas that permanently shaped his approach to his ministry, particularly around issues of race and racial segregation.

Graham began his post-secondary education at the fundamentalist Christian school Bob Jones College, then an unaccredited institution in Cleveland, Tennessee, before moving to the then-unaccredited Florida Bible Institute (now Trinity College of Florida) near Tampa. After earning a two-year degree from there in 1940, he was encouraged to attend Wheaton College, a Christian liberal arts school near Chicago. Considering the possibility that he might go into foreign mission work, and in pursuit of a well-rounded liberal arts education, Graham moved to Illinois to attend Wheaton and major in anthropology.

The Wheaton College anthropology department was established in 1937 by Alexander Grigolia, a charismatic Russian émigré with a doctorate in anthropology from the University of Pennsylvania. The curriculum Grigolia developed reflected the views of Franz Boas, often considered the founder of U.S. anthropology, who was an ardent opponent of the scientific racism (the belief that scientific evidence proved the existence of different racial groups and their inferiority or superiority) prevalent in the early 20th century.

Grigolia’s curriculum seems to have had an impact. From the notes and markings Graham made in some of his anthropology textbooks, we can see that he was an engaged, if inconsistent, student. Several chapters in an introductory text contain prolific underlining. “Shilluk kill hippopotami with a harpoon” caught his attention, as did “Salmon catching Indians of British Columbia put up solid plank houses.” But notably, in a different colored pencil, the following sentence was underlined: “Absolutely pure races no longer exist; and this by itself makes it extremely hard to distinguish existing groups on a racial basis.”

After Graham graduated with a bachelor’s degree in anthropology in 1943, he spent a few years in church-based ministry, and even served as the president of a Christian college, before launching his career as an evangelist in 1949. Speaking at a Los Angeles evangelistic rally, Graham caught the eye of media magnate William Randolph Hearst, who sent a telegram to his many publications that simply read: “Puff Graham.” With that injunction, Hearst’s company began promoting the evangelist. With the media empire behind him, Graham’s natural gifts took him to superstar status within a year.

Although many criticized Graham for how he navigated the racial politics of his day, and he himself voiced regrets later in his life, his exposure to anthropology proved to be pivotal in his stand against segregation and racial hierarchy around the world. He countered prevailing views on race with anthropologically informed arguments to expose the fallacy of different, hierarchically arranged human races.

Early on, as Graham’s ministry grew and he began speaking throughout the country, he quickly had to address the realities of discrimination and racial injustice. For this son of the South, raised in segregated North Carolina, confronting white supremacy in Southern contexts was not easy. Between 1950 and 1954, Graham was not consistent in his response. In 1953, he famously took down the ropes dividing the black and white sections of a rally in Chattanooga, Tennessee, offending his hosts while speaking out against racial segregation. Yet, a few months later, local church organizers in his home state of North Carolina staged a segregated event, and he allowed it. After the North Carolina rally, the Asheville Citizen-Times printed a local supporter’s letter that asked, “Why have the so-called church workers and Christians in our city barred the colored people from the Billy Graham revival? … Why make an example of the Negro because of the color of his skin? Is not his soul as important as yours and mine?” The following week Graham addressed the question “Does the Bible teach the superiority of any one race?” in his nationally syndicated newspaper column “My Answer”:

Definitely not. The Bible teaches that God hath made of one blood all the nations of the world. … Anthropologists have come to two very important biological observations. First, there are no pure races. Second, there are no superior or inferior races. We know from history that all people upon contact have crossed their genetically based physical traits. We know from human anatomy that in fundamental structure all people are identical. As far as biological man is concerned, what he is related to is his cultural environment, rather than to any inherited ability or aptitude.

After 1954, when the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education ruling deemed segregation in public schools unconstitutional, Graham never again held a segregated rally, citing constitutional law and his convictions on racial equality. However, he still received criticism from those who felt his highly individualistic Christianity, which made having a “personal relationship with God” the universal cornerstone of Christian life, kept Graham from addressing discrimination as a social, institutional, and systemic reality. His contemporary Reinhold Niebuhr, a prominent American theologian and commentator, was sharply critical of Graham for promoting a form of Christianity that was “oversimplifying every issue of life.” Niebuhr suggested that, like many white, conservative Protestant Christians, Graham held personally laudable views about race but ignored the larger social, political, and cultural dimensions of social evils like racism and segregation.

While Graham never wavered from his commitment to the importance of individual conversion, it does seem that later in his life he began to see how he might have engaged racism more effectively had he developed a deeper anthropological perspective. In 1986, Graham was interviewed by Parade magazine and asked to reflect on his life. When queried if he had any regrets, Graham replied, “I wish I had gotten more education. If I could have, I would have gotten a Ph.D. in anthropology, to understand the race situation in this country better.”

We might imagine that a growing awareness of the cultural dimensions of racism, nurtured by Graham’s early education in anthropology, led him to wish for this greater anthropological understanding later in life. Although he reached out to Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. to pray at his New York crusade in 1957, Graham later expressed regret that he did not march with King and other civil rights leaders in Selma, Alabama, in 1965. But he did issue a strong statement against racism when he served as honorary co-chair (along with Coretta Scott King) of a 1999 international Baptist conference on racism held at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, Georgia. The 80-year-old Graham wrote,

Racism may be the most serious and devastating social problem facing our world today. It divides humans and nations from each other, and is the root cause of many of the wars and conflicts that rage across our globe. Racism is a deadly poison, which never brings good, resulting always in a bitter harvest of hatred, strife, and injustice.

It seems toward the end of his life, Graham could see that beyond the scientific evidence anthropology marshaled to support racial equality, anthropology could also expand his sense of the cultural and social contexts of race and racism. He learned to see more clearly the broader contexts in which all kinds of human evil—and human virtue—are able to flourish.

This work first appeared on SAPIENS under a CC BY-ND 4.0 license. Read the original here.

References

Mar 13, 2019

Mar 6, 2021

Feb 18, 2026