On December 11, the long awaited coronavirus vaccine finally received an emergency approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, offering hope to many who’ve been monitoring its development closely. Developing this vaccine depended greatly on understanding the biological structure of the virus. The mRNA vaccine, which was the first of its kind to make it this far in the clinical trials, is designed to teach our cells to produce a key viral recognition structure. This recognition structure, known as the spike protein, is a crucial part of the virus that promotes entry to human cells and eventually triggers our immune responses. The presence of these proteins are necessary for our bodies to produce the right antibodies to fight and protect us against the real virus.

In order to study such intricate structures scientists today rely on a technique called cryogenic electron microscopy (cryoEM). This technique is able to resolve structural features down to 2 angstrom resolution, equivalent to 0.1 nanometer or one ten-billionth of a meter. The development of this groundbreaking technique in and of itself was worthy of a Nobel Prize. Unlike a conventional light microscope that uses glass to focus light onto the sample, an electron microscope uses a magnetic coil to focus electrons onto the sample.

Our first glimpse of the Coronavius

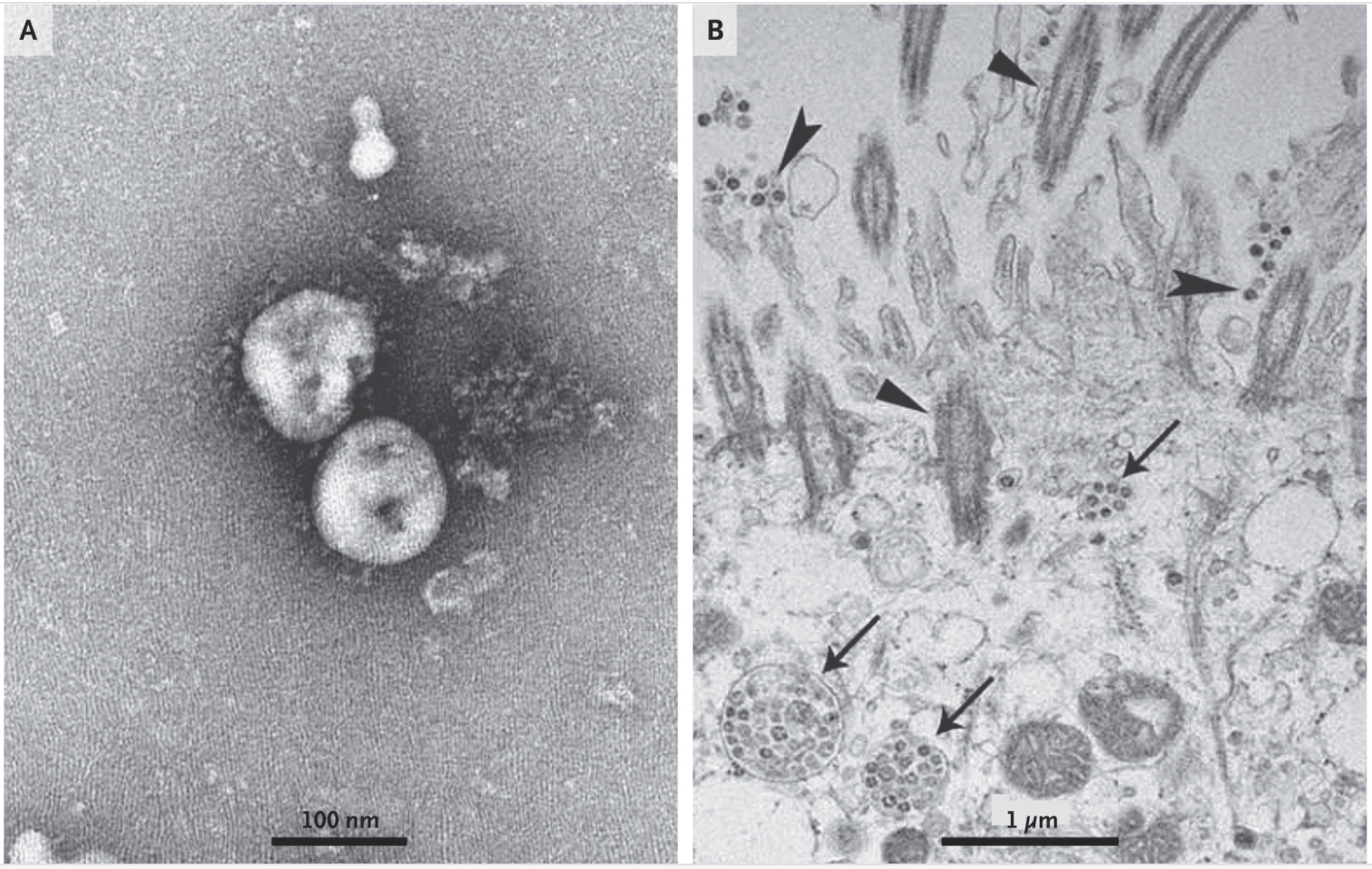

The world gained its first glimpse at the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) back in February 2020 when the China Novel Coronavirus Investigating and Research Team published images of the viral particle they’d taken using a cryoEM.

These electron micrographs were black-and-white, a result of electrons passing through empty areas of the sample (resulting in dark areas) or bouncing from the dense structure (resulting in light areas). Based on these images, scientists were able to deduce the dimensions of the virus. Its diameter varied from about 60 to 140 nm. Distinctive spikes, about 9 to 12 nm in length gave the virus an appearance like a solar corona.

Such “colorless” depictions of a virus structure is common to scientists who frequently visualize and identify similar viral features. Yet to many who are less familiar with such techniques, these images may appear abstract, mysterious, or even uninteresting.

Alternative ways of visualizing the Coronavirus

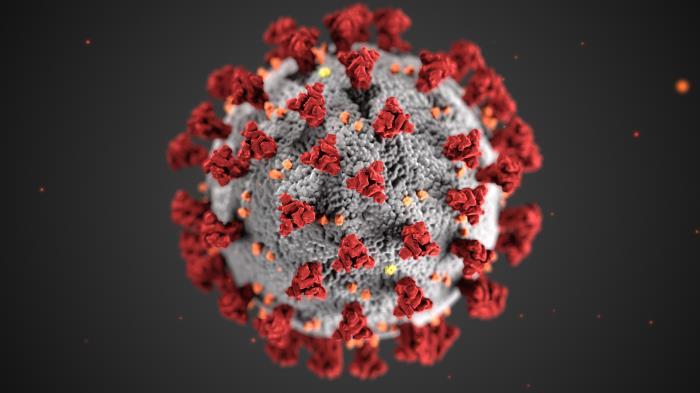

In order to present the information in a more accessible way, many illustrators have gravitated towards digital renderings like the one created by CDC medical illustrators, Alissa Eckert and Dan Higgins. “Creating it with lifelike textures that make you feel like you can touch it brings it closer to reality. It is a way to take something complex and abstract and make it tangible. We gave the virus a face,” said Eckert and Higgins. Images like these not only compliment the news stories that contain them but convey an equally important message about the virus to the public that the colorless and technical micrograph alone is unable to achieve.

Although more common, digitally-colored micrographs, 2D/ 3D schematics, and cartoons all include, strictly speaking, scientific inaccuracies. The CDC depiction of coronavirus, for example, did not show the dynamic interaction of the spike proteins (here shown in red) as they latch flexibly on the surface of the virus in multiple ways. The vacuum background also suggests that the virus can exist in isolation of the complex microenvironment that it would usually inhabit. This is where striking a balance between scientific accuracy and aesthetics can really help bridge this gap between the expert and layperson – and there is arguably no one who does this better than David Goodsell.

Goodsell’s approach to illustrating the Coronavirus and beyond

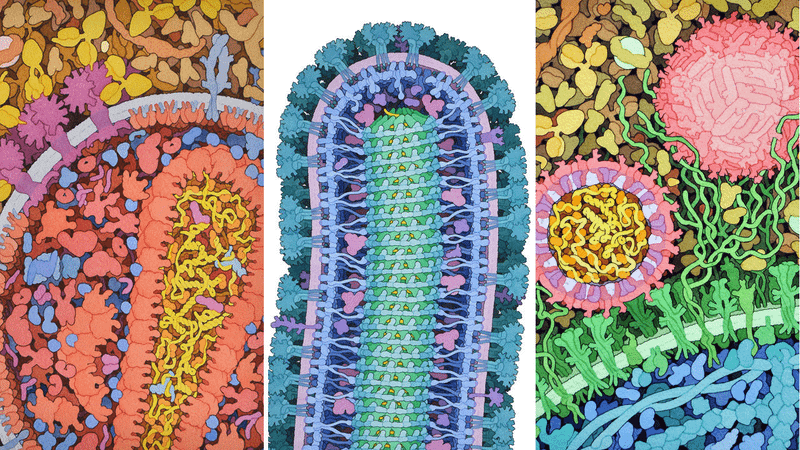

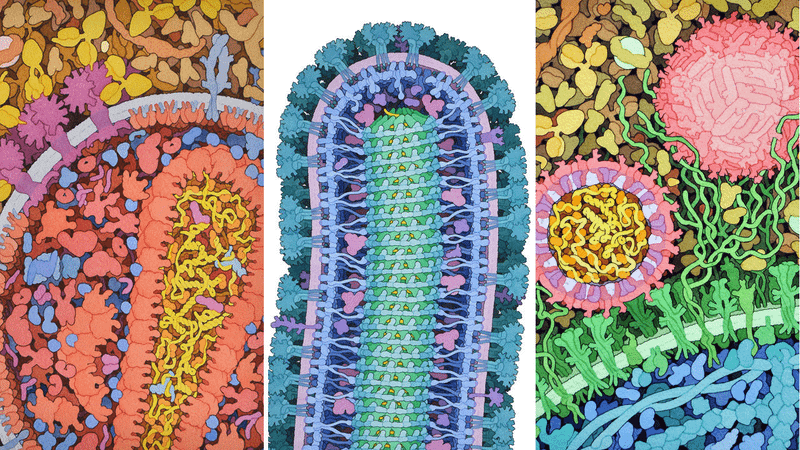

Over the last 25 years Dr. David Goodsell has created stunning watercolor paintings of cells and viruses. As an accomplished computational biologist ( h-index of 59), Goodsell works to accurately represent scientific data in his artwork. His paintings are, in some senses, scientific drawings. Dr. Goodsell explains, “When called upon to share our scientific results with the world, scientists are faced with a challenge: we must select appropriate representations to express our results clearly and unambiguously.” At the Center for Computational Structural Biology, Goodsell and coworkers use computationally sophisticated methods to study cellular function in relation to their intricate molecular structure.

During the pandemic, Dr. Goodsell painted a portrait of the coronavirus, which was later featured on the cover of Nature. He later produced numerous other illustrations of the novel coronavirus, expanding his existing repertoire of virus illustrations which included Ebola, HIV, and Zika virus.

Finding beauty in unlikely places

Dr. Goodsell’s illustrations integrate information from peer-reviewed publications on the viral atomic structures, molecular weights, and electron micrographs. Relying on the current state of knowledge, these illustrations are aesthetically pleasing without compromising scientific accuracy. While ‘beauty’ may sound like an unlikely description to give a deadly virus, it seems to be an apt description. “You have to admit, these viruses are so symmetrical that they’re beautiful,” he said in an interview with the NY Times. “I want people to think of viruses as being an entity that we can learn about and fight. They’re not nebulous nothings.”

The evolving nature of scientific discovery means that sometimes we simply don’t have the full picture, and Dr. Goodsell isn’t hesitant to openly admit this. In fact, the full-length structural analysis of the coronavirus spike protein, which was key information in the current vaccine development, was only recently revealed in Science magazine in October.

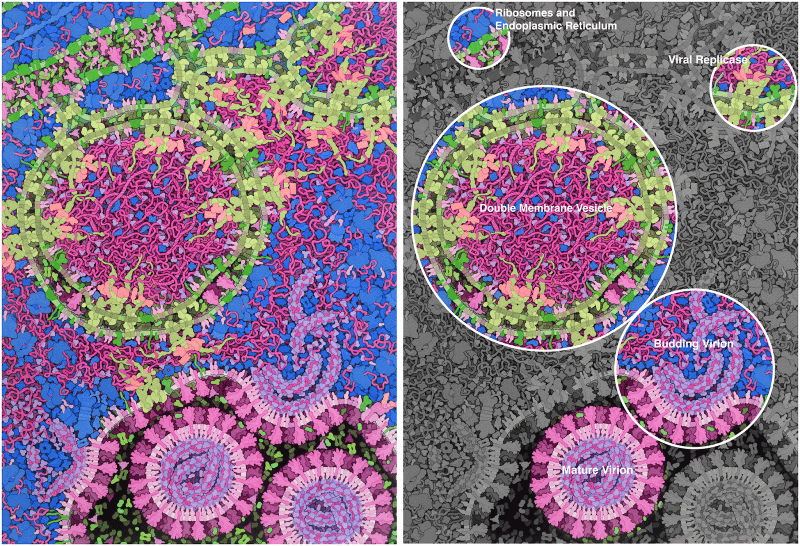

In the following depiction of coronavirus replication and budding, Dr. Goodsell deliberately highlighted where his illustrations were drawn out of speculations. Embedded in the caption for this image was a clarifying statement indicating that

“the illustration integrates the current state of knowledge, but many aspects of the virus and its life cycle are still actively being studied, so portions of the illustration are speculative. Note that some features, such as RNA, needed to be slightly exaggerated in size/width, given the minimal size of features that could be depicted using black outlines of discernable width at the consistent magnification of 1,000,000× that was used for the original watercolor painting.”

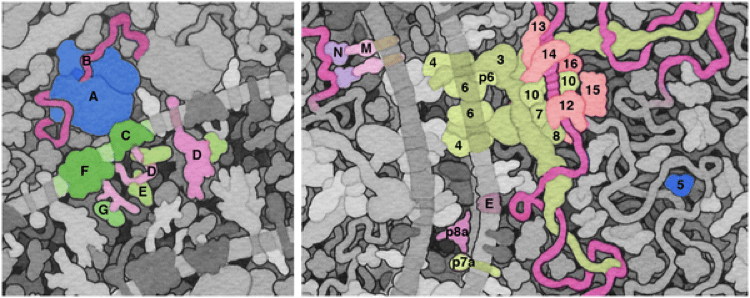

Likewise, on the following image, he explained that “the sizes and shapes of proteins are based on structural results and known interactions, but the arrangement of subunits in the replicase is speculative.” Such captions are not-so-common in scientific literature where schematics are often wireframes, used to convey functionality, composition or mechanism of action. As such, shapes and size scaling in diagrams are frequently overlooked, or at its worst – potentially misleading. It may even suggest that things have been figured out. What is helpful about Dr. Goodsell’s approach is that by sharing these speculations publically, ambiguity is diminished and further investigation is encouraged.

Bridging the gap between art and science

The amazing artwork by Dr. Goodsell may seem to be a surprising twist to his career. While holding a position as an Associate Professor of Molecular Biology at the Scripps Research Institute, he explained that “art and science provide different but complementary ways to explore the world, and I enjoy working in that space that bridges the two disciplines.” The fast growing digital media technology today has meant that many scientific illustrators today mainly work on computer-aided techniques. Dr. Goodsell himself who uses watercolor for most of his illustrations acknowledged this changing era: “I am happy to report that the need for this type of hand-painted rendering is rapidly becoming obsolete.” His recent initiative at CellSpace features computer-rendered illustrations that are produced through collaboration with aspiring artists. Many of his images, such as the paintings of the coronavirus, are available under creative commons licenses, made free for all to enjoy and distribute.

Effective data visualization captures our attention and imagination. Not only that, it communicates scientific information, it also promotes wonder, evokes emotions and can lead to action. The advancement in computer science and digital technology, the string that ties science, art, truth and aesthetics together may be drawn much closer than ever before. The coronavirus vaccine breakthrough is just one example of the growing potential that computational and structural biology and even art can bring.

References

- Bangaru et al., Science, 370, 1089–1094 (2020)

- Goodsell et al., PLoS Biol 5, e308 (2007)

- Goodsell et al., PLoS Biol 18, e3000815 (2020)

- Huang et al., Acta Pharmacol Sin 41, 1141–1149 (2020)

- Prasad et al., Indian J Med Res, 15, 241–243 (2020)

- Turoňová et al., Science 370, 203–208 (2020)

- Zhu et al., N Engl J Med 382, 727-733 (2020)

Links

- https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2019/04/meet-scientist-painter-who-turns-deadly-viruses-beautiful-works-art

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000815.g001

- https://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article/figure?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.3000815.g002

- https://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article/figure?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.3000815.g003

- https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/pfizer-and-biontech-celebrate-historic-first-authorization

- https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/different-vaccines/mrna.html

- https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/health/coronavirus-unveiled.html

- https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-00341-9

- https://www.nature.com/news/cryo-electron-microscopy-wins-chemistry-nobel-1.22738

- https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmoa2001017

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7224615

- https://www.cdc.gov

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zszPyKtBVJg

- https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/17/us/coronavirus-cdc-design-trnd/index.html

- https://phil.cdc.gov/Details.aspx?pid=23311

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/niaid/albums/72157712914621487

- https://innovativegenomics.org/free-covid-19-illustrations

- https://www.drugtargetreview.com/news/57287/3d-visualisation-of-covid-19-surface-released-for-researchers

- https://ghi.wisc.edu/covid-19/art-and-the-coronavirus

- https://science.sciencemag.org/content/370/6513/203

- https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=MACxbNAAAAAJ&hl=en&oi=ao

- https://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.0050308

- https://ccsb.scripps.edu

- https://www.nature.com/nature/volumes/584/issues/7821

- https://pdb101.rcsb.org/sci-art/goodsell-gallery/coronavirus-life-cycle

- https://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.3000815#pbio.3000815.ref002

- https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/30/us/coronavirus-cases-california-new-york.html

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41401-020-0485-4

- https://science.sciencemag.org/content/sci/early/2020/10/19/science.abe1502.full.pdf

- https://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.3000815

- https://ccsb.scripps.edu/goodsell

- https://twitter.com/PLOSBiology/status/1291645863400558597

- https://journals.uic.edu/ojs/index.php/jbc/article/view/6627/5251

- https://ccsb.scripps.edu/goodsell/cellspace

- https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2020-02/uota-bic021820.php

- https://science.sciencemag.org/content/370/6520/1089

- https://www.ijmr.org.in/article.asp?issn=0971-5916;year=2020;volume=151;issue=2;spage=241;epage=243;aulast=Prasad

Dec 30, 2020

Mar 13, 2021

Feb 25, 2026