This article is in a series examining the claims in these three articles by young earth creationist, Andrew Snelling:

Snelling, Andrew. “The Petrology of the Tapeats Sandstone, Tonto Group, Grand Canyon, Arizona.” Answers Research Journal 14 (2021): 159–254.

Snelling, Andrew. “The Petrology of the Bright Angel Formation, Tonto Group, Grand Canyon, Arizona.” Answers Research Journal 14 (2021): 303–415.

Snelling, Andrew. “The Petrology of the Muav Formation, Tonto Group, Grand Canyon, Arizona.” Answers Research Journal 15 (2022): 139–262.

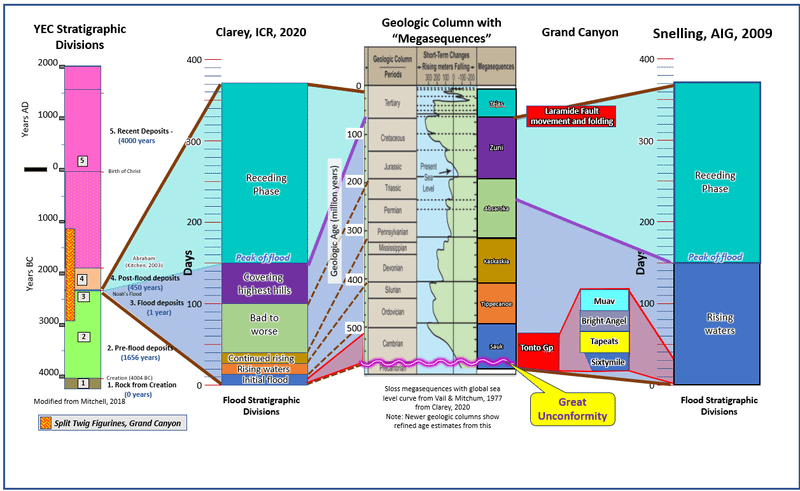

Young Earth Creation (YEC) models propose that geologic units like the formations of the Tonto Group were deposited in a few days or weeks. In Part Two, we will look at two of the four ways that we listed in Part One that the Snelling articles contrast with the consensus geologic understandings developed for these formations. These are:

- How long did it take for the unit to be deposited? Thousands to millions of years vs. a few days.

If the unit were demonstrated to have been deposited more quickly by orders of magnitude than typically proposed, this would be very interesting to geologists. It would no doubt lead to much discussion and many interesting articles. Even so, it would not necessarily have much impact on the understanding of most other sedimentary rock units, either in this area or in other areas around the world. However, if deposition of this unit even took longer than just a month to be deposited, this would mean the unit was not part of the flood deposits and it would challenge Flood Geology (FG) models. If it took thousands of years to be deposited, this would be irreconcilable with any YEC explanations.

- What depositional processes were dominantly involved? Fluvial and tidal processes vs. catastrophic flood processes.

If geologists were to recognize that any of the formations of the Tonto Group were deposited in a different setting with processes dominated by very rapidly flowing water, it would be an interesting find that would certainly make them eager to re-evaluate some other units. However, again, it would say nothing about how most other sedimentary units around the world were formed. Many processes would be incompatible with FG models. For instance, thick alluvial fan deposits conceivably might have formed quickly, but not during a global flood because they would not have formed with rising flood waters. In this particular case, if normal fluvial, tidal or shallow marine processes were evidenced, it would eliminate this interval from the flood model and again challenge FG models in general.

Sedimentary rocks don’t come with speedometers that tell us how fast they were deposited. Snelling has provided many accurate mineralogical descriptions and observations regarding the thin sections, but these do not directly address the depositional processes or rates. Similar sediments can be deposited by several different processes and at different rates. Most of the key evidence for the specific processes and rates comes from other features, some of which will be briefly discussed here.

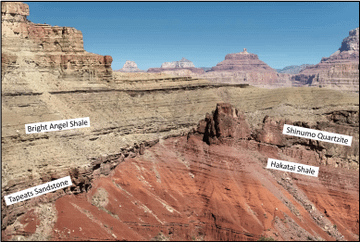

Part of the story involves the surface upon which Tapeats Sandstone rests. The Tonto Group is separated from the rocks below it by a major erosional surface, known geologically as an “unconformity”. In fact, this unconformity is known as the “Great Unconformity (GU)”. Both Snelling and Clarey have published books interpreting this surface as the base of deposits from Noah’s flood. It certainly is widespread and at least roughly equivalent surfaces are present in multiple continents. How did this form? Snelling describes the origin this way:

However, before the Tapeats Sandstone was deposited there had to be a prolonged period (days or more) in which there was a significant amount of continental-scale erosion to bevel the Precambrian (pre-Flood) land surface to produce the Great Unconformity.12

YEC authors propose that this was driven by “catastrophic plate tectonics”3 with “continuous intensive high-energy storms and tsunamis due to the hot waters erupting from the fountains of the great deep.”4

Two obvious issues are brought up by geological studies in the Grand Canyon area. First, the Great Unconformity has been demonstrated to be a composite surface that resulted from multiple widely separated phases of erosion.5 In fact, the sharp angularity found in the Grand Canyon region goes away when it is correlated northward into the Great Basin.6

The second issue regards the sediments underlying the unconformity. Here is an analogy that may make it clear what happened. If you have ever left a chunk of cheese out for a long time, you know that it changes, becoming harder and drier and a crust forms on the outside. Imagine that you have such a piece of cheese and you take a knife and cut a deep trough down into it. Next you cover it with a mixture of sand and gravel. That is sort of what happened at the GU. The surface was exposed for a long period of time and the rocks at the surface were chemically weathered, like the cheese crust. Later the Precambrian rocks were eroded and some of the weathered rock was carried away, leaving unweathered rock at that ancient surface. Eventually the eroded area was covered with sands and gravels that later hardened to sandstones and conglomerates. Just as in our illustration where sands were deposited directly on “fresh” cheese in the trough, the sands and conglomerates of the Tapeats Sandstone were deposited on unweathered older rock in areas where the weathered rock had been removed by erosion. If the unconformity resulted from catastrophic erosion over a few days, then it would not have been exposed long enough for any significant weathering of the underlying rocks to have developed. As we would expect, little weathering is preserved immediately beneath the GU in many locations, suggesting that these areas were not exposed for long before the Cambrian sediments were deposited. Locally however chemical weathering has been documented in the underlying rocks in the Grand Canyon7. For example, in other parts of North America, thick weathered regoliths are found beneath the GU.8 This indicates that deposition, at least locally, began after the surface was exposed for a period of thousands of years.

Another challenge to FG models comes from the sheer amount of sediment deposited above the GU. Globally, the proposed flood section is often miles thick. In the Grand Canyon area, it is estimated to have originally been 3-6 km (~9,840 - 18,400 ft) thick.9 Where did all of the sediment come from that FG says was deposited by the flood? In his descriptions of the Tonto Group, Snelling goes to great lengths to support the idea that the sediment was largely locally derived, an interpretation consistent with most other published reports. If this is true, how could the 275 to 500 m (900 to 1700 ft) of the Tonto Group sediments have been generated over a few days? The sediment had to include quartz sand (derived from granites and Precambrian rocks), muds, limes, and also siliceous material that became chert (Sixtymile Formation). The proposal of “continental-scale erosion” caused by tsunamis and hurricanes is not supported by the evidence. We know the characteristics of tsunami and hurricane erosion and deposition today. If a global catastrophic flood eroded rocks and then deposited sediment derived from this erosion, we should expect to see the tsunami and hurricane type processes, though perhaps scaled up. These would be recognizable.10 Snelling reports that modeling by Baumgardner11 provides support for cavitation and tsunami origins for the sediment. However, Baumgardner’s modeling has many weaknesses and provides no real support for Snelling’s proposal.12 How does Baumgardner account for limestone and other carbonate rocks or evaporites? He doesn’t despite the fact that these represent 20% of sedimentary rocks around the world.

If we use some of the measured thicknesses provided by Middleton and Elliott13 and estimate the duration for Tonto deposition reported by Snelling (Figure 1), we can determine the average sedimentation rates predicted by Snelling’s model. The Tapeats Sandstone would have averaged approximately 9-30 m/day (28-100 ft/day). When we include the Bright Angel and Muav formations, the average increases a bit to 11-34 m/day (36-111 ft/day). These are enormous rates of deposition. These rates can actually be expressed as averaging 0.5 to 1.4 m/hour (1.5-4.6 ft/hour)! This proposal is that a lot of sediment was deposited in a hurry. What if the sedimentation wasn’t continuous over the predicted time? That would mean the rates were even faster when the deposition was active!

In order to get the sediment moving, Snelling proposes that flow rates “ranged from 1.5 m/sec in the lower parts to 1 m/sec in cross-bedded units”.14 Such rates sustained over a broad area would have meant enormous discharge rates. Discharge rates and depositional rates like these are vastly beyond normal rates, but we do have exceptional examples where such flow and depositional rates occurred. These provide us examples of what to expect if processes were much bigger than what we see in the present. Let’s briefly look at examples.

First considering the flow rates, geologists recognize that high flow rates forming large deposits have occurred. Are they comparable? Just as after a car accident, it is possible to examine the wreckage and estimate how fast the cars were moving, we can estimate how fast the flow was moving that caused a sand deposit by examining it. A global catastrophic flood would certainly be larger than typical floods that have occurred around the world in our lifetimes. In this case, like many others, the present is not the entire key to the past. Dr. Paul Carling and Dr. Xuanmei Fan15 describe examples of this in the geologic record known as “megafloods” or “superfloods”. Such rare events have occurred and left distinctive deposits. Such floods move sediments at rates similar to what Snelling claims for Noah’s flood. Such large flows are high unidirectional events that extended over broad areas. Grains from such events are unusual. Carling and Fan16 report that they are “distinctive, being dominated by comminuted (smashed) grain-size distributions, which contrast to the sediment deposits of more moderate floods”.

This study of megafloods provides evidence for what we should expect in terms of lithologic characteristics from deposits from large, high velocity flows. If a global catastrophic flood resulted in the Tapeats Sandstone, it should share key characteristics with such megaflood deposits. While some shattered (comminuted) clasts may be present in the Tapeats Sandstone, they apparently are exceptional. The reviewed reports examine the petrology of the Tonto group, concluding that it is best explained by rapid erosion and deposition by water moving at high speeds. However, nothing was shown that does not fit well as sediment deposited by various normal depositional processes. The model that all materials proposed to have been deposited by the flood were generated by “catastrophic erosion of bedrock via cavitation to produce the sediments that were rapidly deposited on the continental plates as shallow waters moved rapidly around the surface of the rotating globe”17 is just not supported by the slides that are shown. For one thing, we don’t see evidence of the shattering of comminuted grains. The deposits just don’t show evidence of the predicted flow rates.

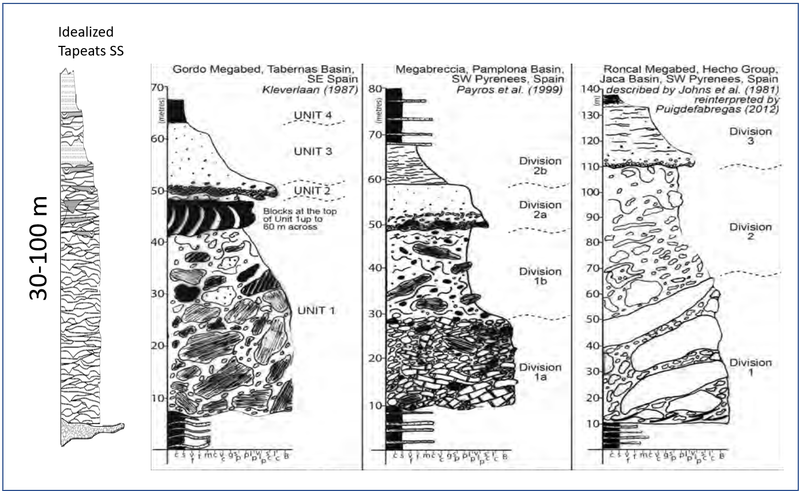

Megaflood deposits, however, are not the only option for rapid deposition. Deposits in Spain described as “megaturbidites” or “megabeds” can be up to 656 feet (200 m) thick.18 Such units are recognized in many basins and are recognized as “event deposits”, such as might result from major earthquakes.19 Geologists recognize that such catastrophic events have occurred in the past and resulted in thick depositional units that were formed quickly. YEC demands that all of the Tonto unit was formed by such events. Are they comparable? Figure 220 shows that the scale of Tapeats channels and beds is much finer. The Tapeats Sandstone resulted from hundreds and probably thousands of separate depositional events of many types. The megabeds show what happens when something, such as a major earthquake, hits an area with a large amount of unstable sediment, generally associated with a sea level drop. Such resulting deposits are normally deposited over limited areas (i.e., doesn’t cover a basin as the Tonto sediments do) and has several stages of development even though it results from a single event. The depositional rate for such a limited deposit may be comparable in terms of the depositional rate in Snelling’s model, but it likely did not involve the flow rates that Snelling postulated. So again, the Tonto Group sediments do not have characteristics such as would be formed by megaturbidites.

Geologists have studied the Tonto Group in a number of major studies over the area and described the environments in different ways.21 Most recognize that the depositional environments varied both around the area and through time (vertically).

Middleton and Elliott22 described the environments for the Tapeats Sandstone this way in what generally encapsulates the leading consensus of most geologists:

a variety of fluvial, nearshore, and shallow shelf environments. Braided stream and intertidal-to shallow-subtidal deposits of the Tapeats Sandstone grade seaward into a complex array of shelf sands and muds of the Bright Angel Shale (BAS). Shelf sedimentation was influenced by both tidal and storm currents. Sand ridges, sand waves and broad areas where fine-grained siliciclastics were deposited from suspension settling following storms and during fair-weather periods characterized the shelf. Farther offshore, carbonate islands dotted the shelf. Here, the carbonate buildups were characterized by intertidal and possible supratidal zones separated by deeper water areas where tidal currents were active and finer-grained carbonate sediments were deposited.

They are describing a set of depositional process much like normal sedimentation today and suggest rates were not radically different. If the formations in the Tonto Group do not have characteristics of megabeds or megafloods, do the characteristics fit the model of slower deposition shaped by streams, tides and normal marine processes? Here we will highlight several examples that we find fit the consensus models, but do not fit the proposal of deposition in a few days by a catastrophic flood.

We will look at examples of features in the sedimentary rocks, characterized as sedimentary structures, features that developed during deposition that help us to understand the processes involved. A short summary of such features is found on Wikipedia.23 Many bedding types and sedimentary structures are non-unique in terms of the environment in which they form, however, some form only under very limited conditions. All features identified are consistent with “a variety of fluvial, nearshore, and shallow shelf environments” but some are particularly diagnostic. Snelling recognizes these features and proposes alternative explanations which we can consider.

Herringbone Cross-stratification

When sediments are deposited by moving wind or water, the bedforms vary based on the media and the velocities. When the resulting small-scale features are at an angle to the main bedding, this is called cross-bedding or cross-stratification. In many places is very simple to recognize the direction of sediment transport from the orientation of the cross-bedding. In some particular cases, the cross-bedding shows that the current reversed direction over and over again, in what were relatively short time intervals. Where might we expect to find strata that developed by the reversal of flow directions over short time frames? We find such flow reversals all around the world in predictable tidal cycles. Bedding reflecting this is known as “herringbone cross-stratification”. It is not hard to figure out where the name came from. Tides in the present and past developed many types of stratification but when found, herringbone cross-beds are considered diagnostic of tidal environments.24 Many authors report “herringbone” cross-stratification to be common in all of the Tonto formations.25 Snelling also observed them in the Tonto group and states: “The herringbone cross-stratification appears to reflect the bimodal-bipolar flow of the tidal currents.” (p. 195). It is hard to understand why there would be flow reversal deposition in a catastrophic flood deposit moving at the predicted rates. Herringbone cross-beds are one of several indicators of tidal deposits where we can count the cycles and be confident that the time represented by the sediments is no less than the number of cycles divided by four. We recognize that sedimentation probably shifted out of the area at times, meaning that more days may actually have elapsed. A few days of deposition for just a few feet of sediment doesn’t really work in the FG timelines. Remember that Snelling proposed that the Tapeats was deposited “within 3–10 days”. If one small unit took several days to form, not much time is left for the rest of the rock. Alternating periods of low to moderate flow such as are demonstrated by herringbone sets do not reflect flow conditions from megabed formation or megaflood deposits and thus would not have been part of a catastrophic deposit with high flow rates such as are proposed by Snelling.

Snelling describes another type of cross-beds known as hummocky cross-stratification (HCS) that is found in the BAS and reports that they are inconsistent with tidal deposits. Snelling reports, “The hummocky cross-stratified sandstone beds pinch and swell along outcrop, grade laterally into herringbone cross-stratification beds, and both their lower and upper contacts are sharp or erosive.”26

It is true that sedimentologists normally consider HCS to be indicative of storm deposition farther offshore. However, beautiful examples of HCS are found in tidal deposits in South Korea.27 Once again, these fit well in the range of environments proposed by previous workers. The association with herringbone cross-stratification is consistent with storm deposits in settings with tidal deposits if the HCS formed similarly to those in South Korea.

Mudcracks

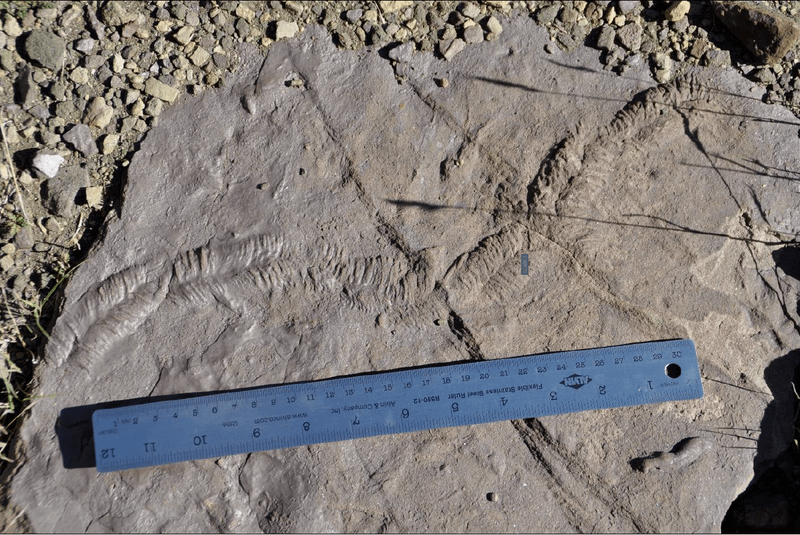

The next key sedimentary structure that studies of the Tonto Group have observed is polygonal fractures interpreted as desiccation features known as mudcracks. These are commonly observed all around the world in areas where exposed sediments become wet and then dry out. (Figure 3). Rose, Hagadorn et al., Hill and Mosier, Hardy, and Wanless28 (in the presence of polygonal features BAS) all report the interpreted as desiccation cracks or mud cracks in the Tonto Group.

These polygonal features are common indicators of at least some time of exposure and drying of sediment. The presence of such features is difficult to reconcile with either the rapid rate of sedimentation or the limited time available in FG models because their formation demonstrates periods when deposition stopped.

Hill and Moshier29 published a photograph of mud cracks from the Tapeats (Figure 4). Snelling argues that “these cannot possibly be “mud” cracks because these features are in a clay-poor sandstone, not mud. And as seen in their photograph of modern mud cracks, when the mud dries the polygonal shapes become concavely arched, whereas the claimed fossilized “mud” cracks are flat”.30

Snelling’s comments are not persuasive for several reasons. He argues that the pictured examples are from a clay-poor sandstone. It is true that some mud is essential; they can develop in sandy mud.31 The location and lithologies for the example published by Hill, et al.32 have not been given, but Snelling notes the presence of shaly beds both in his figure 18a,33 taken from McKee34 showing a shale bed. Dr. Snelling also noted “green muddy beds” in his Tapeats Sandstone Supplement descriptions of the Monument fold.35 Without knowing the location of the Hill example, it is not possible to know the detailed lithology there and some clay in that location is possible. Snelling’s observation of the lack of concave arch apparent in the feature does not seem to be valid, as the modern example in Figure 3 illustrates. Snelling36 claims that limestones such as in the Muav Limestone cannot have mudcracks despite the reports by geologists such as Wanless and Rose.37 Actually, mudcracks are commonly reported in modern lime tidal flats such as in the Bahamas.38

Examples from the Tonto do not contain tracks from dinosaurs or mammals because such animals were not living at the time. Cambrian mudcracks have been found with tracks from trilobites, extinct arthropods that were very common then.39 Rocks from the Mesozoic, the age of the dinosaurs, include dinosaur tracks on or associated with mudcracks in many places around the world. These make perfect sense in sediments in settings that developed over long periods of time but do not fit in the catastrophic deposits of a giant flood.

Pauses in sedimentation of at least days are also indicated in the Muav Limestone as all investigators report the presence of “flat-pebble conglomerates”, often using them as important marker beds. They consist of pebbles with a distinct flattened dimension. Snelling40 says,

The origin of the clasts obviously required early lithification by cementation and/or compaction because they are likely derived by erosion of the earlier-deposited sediments within the same depositional basin.41

Regardless of how the Muav conglomerates formed, the demand that sedimentation paused for long enough for cementation to have taken place is valid. The many flat-pebble beds dictate that sedimentation paused many times. We don’t know exactly how long the pauses were, but several days would seem to be a minimum. Overall, the presence of sedimentary structures like herringbone cross-bedding, mudcracks and flat-pebble beds demonstrate repeated pauses in sedimentation and are very problematic for FG models.

Biologic Evidence

Fossil Occurrence

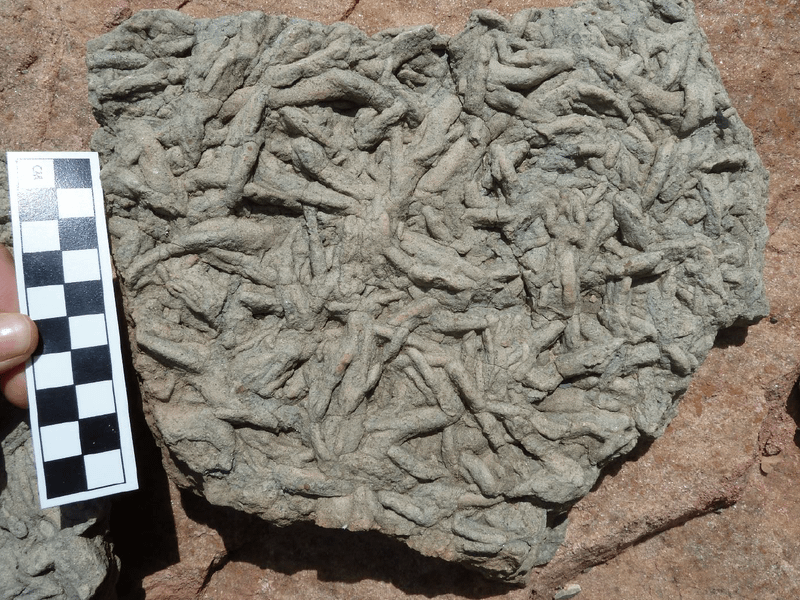

One important clue used to learn how rocks were laid down is to look at the fossils preserved in them. Fossils from the Tonto Group include brachiopods (eleven species), trilobites (fifteen species) (Figure 5), other arthropods species including ostracod-like species of the order Bradoriida (eight species) and two early echinoid species.42 These show that a variety of fauna were present. In addition, trace fossils demonstrate that soft-bodied animals were there as well.

Assessing flood geology on the whole, it is difficult to understand why we do not find any indications of more modern lifeforms, particularly in the units deposited in the early flood. We don’t find plant pollen or forams or fish fossils or many, many other forms that would be common today, even in rapidly deposited sediments. Where were the clams or nautiloids? Can you imagine what the finding of a fossil dolphin bone in Cambrian rock would mean? It seems clear that they were not present, neither in the area that sourced the sands nor in the marine waters where much of the unit was deposited in. It is interesting that the BAS does contain microfossils. Spore-like fossils, known as cryptospores, are found in many samples, demonstrating that microfossils would have been preserved if present.43

Trilobite from BAS (Dolichometoppus productus and Alokistocare althea)

Trace Fossils (Ichnofossils)

The most common evidence for biologic activity that is found is in the form of trace fossils (ichnofossils) and these fossils are important in this discussion. These include grazing trails and various markings that were formed before the sediment hardened, typically on or near the surface at the time. Examples of these are shown in Figures 6 and 7.44 These are most common in the BAS, but are also found in the Tapeats and both will be discussed here. One could argue that trilobites or brachiopod fragments were transported to their final position, perhaps rapidly. Trace fossils were not. These were formed after sediment deposition. These, like the mudcracks, reflect pauses in sedimentation of some duration. This is not to say that months or years were absolutely required, but how much time is available in FG models? Deposition that averaged 0.4 to 4 m/hour (1.2-4 ft/hour) would not have left time for grazing. The time available for pausing sedimentation would have been incredibly limited in such models.

Flood geologists, including Snelling, recognize that the trace fossils represent evidence that living animals were active during the period when the sediments were laid down. Animals in marine, tidal and nearshore environments form similar features today. The cast of animals has changed, but the ecological niches were the same. FG demands that the traces be part of very rapid deposition, with the reworking of the sediment (bioturbation) accomplished by the animals caught up in rapidly deposited flows. They would have been the dying acts of animals as they were buried.

The simpler interpretation is that the trace fossils of the Tonto Group reflect large populations that existed for an extended time. They formed at multiple levels. It is not as though there was a single episode of biological activity. The traces in the units, particularly the BAS show that a complete ecosystem was present with the same feeding styles we find today.45 Multiple levels of highly active biogenic activity such as these are not compatible with the rates of deposition demanded by FG models. These were not some sort of death assemblage, transported into place, where a few survivors dug around before finally succumbing to the pressure of burial. That seems obvious from examples such as were shown in Figures 6 and 7. These were thriving communities that lived for some period of time before sedimentation shifted into the area again and buried them. All are consistent with tidal environments, though certainly some could have formed over time in deeper water environments.

Algal mats (Stromatolites)

The Muav Limestone in at least some places, includes banded units known as stromatolites.46 These laminated units formed as sediment was trapped by microbial mats of cyanobacteria (blue-green algae). They demonstrate alternate periods of flooding and exposure, typically by tides. We find mounds of them growing today in tidal environments in Australia as well as throughout the geologic past. Snelling recognizes that actual stromatolites in the Muav Formation would invalidate his flood interpretation.47 He notes that no one seems to have done detailed work to demonstrate that these features were formed by algae, saying: “Yet, Resser, nor anyone else, has checked the Muav Formation’s Girvanella limestone to confirm whether Girvanella filaments are present with these spherical structures”.48

Should we doubt the reports of stromatolites in the Muav until this work is done? If these were the only Cambrian stromatolites in the region, this would be a real concern. In fact, stromatolite development is extensive above the Tapeats in the Cambrian Carrara Formation in Nevada.49 Cambrian and earlier stromatolitic reefs are present in many parts of the world. YEC geologist, Dr. Ken Coulson documented Late Cambrian stromatolitic reefs in the Notch Peak Formation in Utah in great detail.50 These thick intervals of stromatolitic reefs that clearly grew in place over long periods of time are stratigraphically younger than the Muav limestone and well above the GU. Coulson recounts Cambrian stromatolitic reef development in many parts of North America. (Figure 8).51 He recognizes that reef development, including stromatolites, where they are developed, are incompatible with a flood interpretation. Based on this, he rejects considering the GU as the base of global flood deposits. Reefs of many types are found throughout the Phanerozoic rock record making it difficult to include any significant section as a result of such a flood.

Summary

The depositional features that are observed in the Tonto Group do not prove that millions of years were involved. They do demonstrate that more than a few days or weeks were required. The units were deposited over chemically weathered rock that is preserved in places, suggesting exposure for a long period of time. The sheer volume of sediment present is inconsistent with YEC models. Each of the three formations resulted from many different depositional events, not one catastrophic flood. We compared the features found here to catastrophic deposits recognized by geologists. We don’t find features that are characteristic of dramatic rapid deposition such as comminuted (smashed) grain-size distributions of megaflood deposits or thick chaotic beds like megabeds. All of the sediments show evidence of slower fluid flow than Snelling proposed, except perhaps over limited storm periods and then over limited portions of the units.

We found many smaller scaled features that demonstrate pauses in sedimentation and deposition that, at least in portions, included normal processes and rates. Tidal deposition is strongly supported by herringbone cross-stratification, mudcracks, extensive bioturbation and trackways. Stromatolitic units including reefs are found in the Muav Formation and in other Cambrian units such as in Utah. No one claims that reefs grew during a one-year flood. The combination of fluvial, tidal and marine deposition over a long period of time explains all of the observations, while catastrophic flood processes are not evidenced.

References

Baldwin, Christopher T., P. K. Strother, J. H. Beck, and Eben Rose. 2004. “Palaeoecology of the Bright Angel Shale in the Eastern Grand Canyon, Arizona, USA, Incorporating Sedimentological, Ichnological and Palynological Data.” Geological Society, London, Special Publications 228 (1): 213–36. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2004.228.01.11.

Baumgardner, John. 2018a. “Numerical Modeling of the Large-Scale Erosion, Sediment Transport, and Deposition Processes of the Genesis Flood (Revised).” Answers Research Journal, 11, 149–170.

Baumgardner, John. 2018b. “Understanding How the Flood Sediment Record Was Formed: The Role of Large Tsunamis.” Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism 8 (1). doi:10.15385/jpicc.2018.8.1.29.

Blakely, RC. 2013. “Key Time Slices of North America.” Key Time Slices of North America. Colorado Plateau Geosystems Inc.

Bozetti, Guilherme, Bryan Cronin, B. Kneller, and Mark Jones. 2018. “Deep-Water Conglomeratic Megabeds: Analogues for Event Beds of the Brae Formation of the South Viking Graben, North Sea.” In Rift-Related Coarse-Grained Submarine Fan Reservoirs; the Brae Play, South Viking Graben, North Sea. doi:10.1306/13652180M1153809.

Carling, Paul A., and Xuanmei Fan. 2020. “Particle Comminution Defines Megaflood and Superflood Energetics.” Earth-Science Reviews 204: 103087. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103087.

Coulson, Ken P. 2021. “Using Stromatolites to Rethink the Precambrian-Cambrian Pre-Flood/Flood Boundary.” Answers Research Journal, 14, 81–123.

Cuven, Stéphanie, Raphaël Paris, Simon Falvard, Elisabeth Miot-Noirault, Mhammed Benbakkar, Jean-Luc Schneider, and Isabelle Billy. 2013. “High-Resolution Analysis of a Tsunami Deposit: Case-Study from the 1755 Lisbon Tsunami in Southwestern Spain.” Marine Geology 337 (March): 98–111. doi:10.1016/j.margeo.2013.02.002.

Dietz, Marianne E., Kam-biu Liu, Thomas A. Bianchette, and Denson Smith. 2021. “Differentiating Hurricane Deposits in Coastal Sedimentary Records: Two Storms, One Layer, but Different Processes.” Environmental Research Communications 3 (10): 101001. doi:10.1088/2515-7620/ac26dd.

Elston, Donald P., Billingsley, Georghe H., and Young, Richard A. 1989. “Correlations and Facies Changes in Lower and Middle Cambrian Tonto Group, Grand Canyon, Arizona.” In Geology of Grand Canyon, Northern Arizona (with Colorado River Guides): Lee Ferry to Pierce Ferry, Arizona, 131–36. American Geophysical Union (AGU). doi:10.1029/FT115p0131.

Fedo, C. M., and A. R. Prave. 1991. “Extensive Cambrian Braidplain Sedimentation: Insights from the Southwestern Cordillera, U. S. A.” AAPG Bulletin (American Association of Petroleum Geologists); (United States) 75:2 (February).

Foster, John. 2011. “Trilobites and Other Fauna from Two Quarries in the Bright Angel Shale (Middle Cambrian, Series 3; Delamaran), Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona.” Museum of Northern Arizona Bulletin, Cambrian Stratigraphy and Paleontology of Northern Arizona and Southern Nevada, The 16th Field Conference of the Cambrian Stage Subdivision Working Group, International Subcommission on Cambrian Stratigraphy, January.

Hagadorn, James W., Kirschvink, Joseph L., Raub, Timothy D., and Rose, Eben C. 2011. “After the Great Unconformity: A Fresh Look at the Tapeats Sandstone, Arizona-Nevada, USA.” Cambrian Stratigraphy and Paleontology of Northern Arizona and Southern Nevada 67: 283–84.

Hardy, Joseph Kirk. 1986. “Stratigraphy And Depositional Environments Of Lower And Middle Cambrian Strata In The Lake Mead Region, Southern Nevada And Northwestern Arizona.” University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Hereford, Richard. 1977. “Deposition of the Tapeats Sandstone (Cambrian) in Central Arizona.” GSA Bulletin 88 (2): 199–211. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1977)88<199:DOTTSC>2.0.CO;2.

Hill, Carol, and Stephen Moshier. 2016. “Sedimentary Structures: Clues from the Scene of the Crime.” In The Grand Canyon, Monument to an Ancient Earth; Can Noah’s Flood Explain the Grand Canyon?, edited by Carol Hill, Gregg Davidson, Tim Helble, and Wayne Ranney. Solid Rock Lectures and Kregel Publications.

Karlstrom, Karl E. 2019. “Parsing Grand Canyon’s Great Unconformity–Composite Erosion Surface From at Least Three Episodes Between 1,350 and 508 MA.” Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs 51 (5) doi:10.1130/abs/2019AM-332195.

Kennedy, Elaine G., Kablanow, Ray, and Chadwick, Arthur V. 1997. “Evidence for Deep Water Deposition of the Tapeats Sandstone, Grand Canyon, Arizona.” Proceedings of the Third Biennial Conference of Research on the Colorado Plateau U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Transactions and Proceedings Series NPS/NRNAU/NRTP-97/12.

Kindle, E. M. 1917. “Some Factors Affecting the Development of Mud-Cracks.” The Journal of Geology 25 (2): 135–44. doi:10.1086/622446.

Korolev, Viacheslav Sergeevich. 1997. “Sequence Stratigraphy, Sedimentology, and Correlation of the Undifferentiated Cambrian Dolomites of the Grand Canyon and Lake Mead Area.” MS Thesis, University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Mángano, M. Gabriela, Luis A. Buatois, Ricardo Astini, and Andrew K. Rindsberg. 2014. “Trilobites in Early Cambrian Tidal Flats and the Landward Expansion of the Cambrian Explosion.” Geology 42 (2): 143–46. doi:10.1130/G34980.1.

Martin, D.L. n.d. “Depositional Systems and Ichnology of the Bright Angel Shale (Cambrian), Eastern Grand Canyon, Arizona.” MS Thesis (unpublished), Northern Arizona University.

McKee, Edwin Dinwiddie. 1945. Stratigraphy and Ecology of the Grand Canyon Cambrian: Part 1. Cambrian History of the Grand Canyon Region. Vol. 1. 563. Carnegie Institution of Washington.

Middleton, L.T. and Elliott, D.K. 1990. “Tonto Group, Chap. 6.” In Grand Canyon Geology, 83-106. Oxford University Press.

Miller, Anne, Lorenzo Marchetti, Heitor Francischini, and Spencer Lucas. 2020. “Paleozoic Invertebrate Ichnology of Grand Canyon National Park.” In Grand Canyon National Park Centennial Paleontological Resource Inventory, Natural Resource Report NPS/GRCA/NRR—2020/2103, 131–70.

Pevehouse, Katie J., Dustin E. Sweet, Branimir Šegvić, Charles C. Monson, Giovanni Zanoni, Stephen Marshak, and Melanie A. Barnes. 2020. “Paleotopography Controls Weathering of Cambrian-Age Profiles beneath the Great Unconformity, St. Francois Mountains, SE Missouri, USA.” Journal of Sedimentary Research 90 (6): 629–50. doi:10.2110/jsr.2020.33.

Ressner, Charles E. 1945. Cambrian History of the Grand Canyon Region: Part I. Stratigraphy and Ecology of the Grand Canyon Cambrian; Part II. Cambrian Fossils of the Grand Canyon. Carnegie Institute of Washington Publication 563. Carnegie Institute of Washington.

Rose, Eben C. 2006. “Nonmarine Aspects of the Cambrian Tonto Group of the Grand Canyon, USA, and Broader Implications.” Palaeoworld, The Fourth International Symposium on the Cambrian System, 15 (3): 223–41. doi:10.1016/j.palwor.2006.10.008.

Sappenfield, Aaron Dale. 2015. “Precambrian-Cambrian Sedimentology, Stratigraphy, and Paleontology in the Great Basin (Western United States).” PhD Dissertation, UC Riverside.

Seguret, M, P Labaume, and R Madariaga. 1984. “Eocene Seismicity in the Pyrenees from Megaturbidites of the South Pyrenean Basin (Spain).” Marine Geology, Seismicity and sedimentation, 55 (1): 117–31. doi:10.1016/0025-3227(84)90136-1.

Sharp, Robert P. 1940. “Ep-Archean and Ep-Algonkian Erosion Surfaces, Grand Canyon, Arizona.” GSA Bulletin 51 (8): 1235–69. doi:10.1130/GSAB-51-1235

Shinn, Eugene A. 1983. “Tidal Flat Environment.” In Carbonate Depositional Environments, edited by Peter A. Scholle, Don G. Bebout, and Clyde H. Moore, 33:0. American Association of Petroleum Geologists. doi:10.1306/M33429C8.

Snelling, Andrew A. 2021. “Tapeats Sandstone Supplement.” Answers in Genesis.

Snelling, Andrew. 2021a. “The Petrology of the Bright Angel Formation, Tonto Group, Grand Canyon, Arizona.” Answers Research Journal 14, 303–415.

Snelling, Andrew. 2021b. “The Petrology of the Tapeats Sandstone, Tonto Group, Grand Canyon, Arizona.” Answers Research Journal 14, 159–254.

Snelling, Andrew. 2022. “The Petrology of the Muav Formation, Tonto Group, Grand Canyon, Arizona.” Answers Research Journal 15, 139–262.

Snelling, Andrew. 2023. “The Carbon Canyon Fold, Eastern Grand Canyon, Arizona.” Answers Research Journal 16, 1-124.

Strother, Paul, and J Beck. 2000. “Spore-like Microfossils from Middle Cambrian Strata: Expanding the Meaning of the Term Cryptospore.” In Pollen and Spores: Morphology and Biology, 413–24. Royal Botanic Gardens.

Wanless, Harold R. 1973. “Cambrian of the Grand Canyon–A Reevaluation.” AAPG Bulletin 57 (4): 810–11.

Wise, Kurt P, and Andrew A Snelling. 2005. “A Note on the Pre-Flood/Flood Boundary in the Grand Canyon.” Origins, no. 58.

Acronyms Used

| Acronym | Full Term |

|---|---|

| AIG | Answers in Genesis |

| BAS | Bright Angel Shale |

| EKM | East Kaibab Monocline |

| FG | Flood geology or flood geologist |

| GU | Great Unconformity |

| HCS | Hummocky Cross-stratification |

| ICR | Institute for Creation Research |

| YEC | Young Earth Creationism or Young Earth Creationist |

Links

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:11570_Grand_Canyon_Fossil_Trilobite_in_Bright_Angel_Shale_(4749628242).jpg

- https://answersresearchjournal.org/petrology-tapeats-sandstone-tonto-group

- https://answersresearchjournal.org/petrology-bright-angel-tonto-group

- https://answersresearchjournal.org/geology/petrology-muav-formation-tonto-group

- https://doi.org/10.1144/gsl.sp.2004.228.01.11

- https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.SP.2004.228.01.11

- https://answersresearchjournal.org/numerical-modeling-genesis-flood-2

- https://doi.org/10.15385/jpicc.2018.8.1.29

- https://encyclopediaofalabama.org/media/figure-3-cambrian-laurentia

- https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/books/book/2142/chapter-abstract/119483465/Deep-Water-Conglomeratic-Megabeds-Analogues-for

- https://doi.org/10.1306/13652180M1153809

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0012825219305641

- https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103087

- https://answersresearchjournal.org/stromatolites-precambrian-flood-boundary

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0025322713000224

- https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2013.02.002

- https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/2515-7620/ac26dd

- https://doi.org/10.1088/2515-7620/ac26dd

- https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/FT115p0131

- https://doi.org/10.1029/FT115p0131

- https://www.osti.gov/biblio/5142087

- https://www.academia.edu/10100674/Trilobites_and_other_fauna_from_two_quarries_in_the_Bright_Angel_Shale_middle_Cambrian_Series_3_Delamaran_Grand_Canyon_National_Park_Arizona

- https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds/6

- https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/gsa/gsabulletin/article-abstract/88/2/199/202052/Deposition-of-the-Tapeats-Sandstone-Cambrian-in

- https://doi.org/10.1130/0016-7606(1977)88<199:DOTTSC>2.0.CO;2

- https://peacefulscience.org/books/grand-canyon-monument-ancient-earth/

- https://gsa.confex.com/gsa/2019AM/webprogram/Paper332195.html

- https://doi.org/10.1130/abs/2019AM-332195

- https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/622446

- https://doi.org/10.1086/622446

- https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds/3332

- https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/gsa/geology/article-abstract/42/2/143/131437/Trilobites-in-early-Cambrian-tidal-flats-and-the

- https://doi.org/10.1130/G34980.1

- https://amazon.com/dp/B00JJ3OC0S/

- https://amazon.com/dp/0195050142/

- https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/sepm/jsedres/article-abstract/90/6/629/587565/Paleotopography-controls-weathering-of-Cambrian

- https://doi.org/10.2110/jsr.2020.33

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1871174X06000400

- https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palwor.2006.10.008

- https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4r02d6xr

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0025322784901361

- https://doi.org/10.1016/0025-3227(84)90136-1

- https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/gsa/gsabulletin/article-abstract/51/8/1235/3811/Ep-Archean-and-Ep-Algonkian-erosion-surfaces-Grand

- https://doi.org/10.1130/GSAB-51-1235

- https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/aapg/books/book/1422/chapter-abstract/107173399/Tidal-Flat-Environment

- https://doi.org/10.1306/M33429C8

- https://assets.answersingenesis.org/doc/articles/arj/v14/tapeats-sandstone-supplement.pdf

- https://answersresearchjournal.org/geology/carbon-canyon-fold-arizona

- https://amazon.com/dp/1900347954/

- https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/aapgbull/article-abstract/57/4/810/555771/Cambrian-of-the-Grand-Canyon-A-Reevaluation

- https://www.grisda.org/assets/public/publications/origins/58007.pdf

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sedimentary_structures

- https://jesusinhistoryandscience.com/?p=2917

Aug 15, 2024

Aug 15, 2024

Feb 9, 2026