Born in Guildford, England, Jon Garvey studied medicine at Cambridge University, and later studied theology through the Open Theological College, University of Gloucestershire. Since 2011, his blog The Hump of the Camel has explored the theology of creation, attracting an extensive readership across the world, and he has also contributed extensively at BioLogos and Peaceful Science. In January 2019 Cascade published his first book, God’s Good Earth, and a year later his second, The Generations of Heaven and Earth. He lives in south-west England, is married, with three adult children and five granddaughters, is a Baptist elder, and played guitar and saxophone semi-professionally until he was recently placed, like everyone else, under house-arrest because of Coronavirus.

Tell us the story behind the book?

You recently published the first book-length response to The Genealogical Adam and Eve, titled The Generations of Heaven and Earth: Adam, the Ancient World and Biblical Theology. This is fitting, because you have been thinking about the ideas here since back in 2010. Can you tell us the story?

I’d not long started researching some of the knotty problems regarding scientific origins and the Bible (the story of how that began is in a post on my blog, the Hump of the Camel) when David Opderbeck published the first article on what became the Genealogical Adam and Eve at BioLogos. The idea of an Adam called from amongst an existing human race was familiar to me from writers like Derek Kidner and C. S. Lewis, but this proposal seemed to give it scientific traction within a traditional theological framework. It looked like the direction to take on Adam and Eve.

I chased up the scientific articles on which his article was based, and began to toss some of the implications around in my mind. When Joshua Swamidass reintroduced the notion in a thread at BioLogos in 2017, it reawakened my enthusiasm. Partly in collaboration with him and the community he formed at Peaceful Science, I wrote a large number of blogs which became the backbone of Generations.

How does your book relate to The Genealogical Adam and Eve?

How does your book relate to The Genealogical Adam and Eve? How is it different? What does it add to the growing conversation?

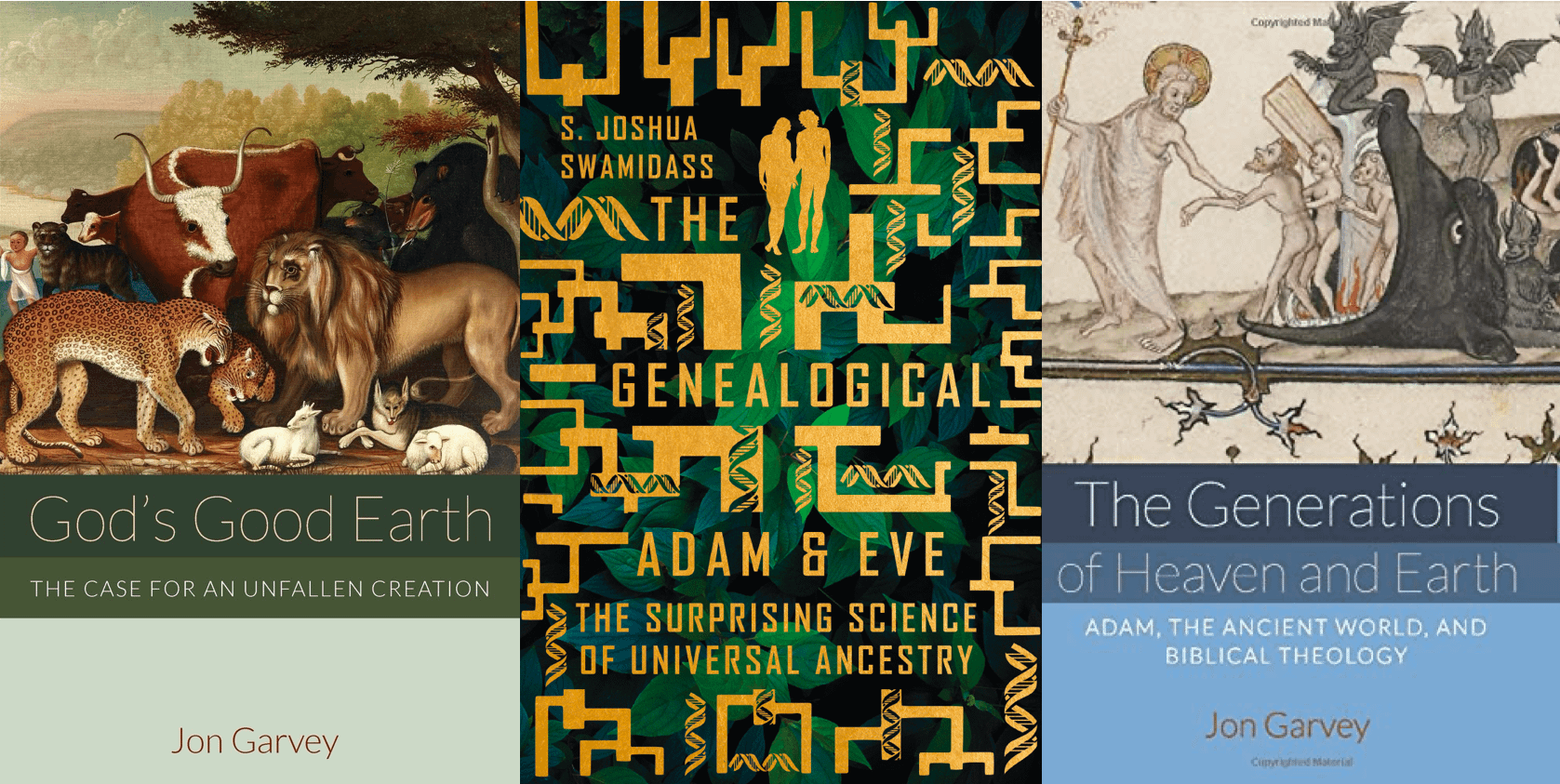

Joshua Swamidass’s The Genealogical Adam and Eve (GAE) is careful to keep all theological options on the table. This befits the introduction of a paradigm that opens up a wealth of new perspectives. Joshua intends for people of many persuasions to apply the paradigm as they see fit.

For example, as a scientist he is open to the idea of a much earlier Adam, as favored by a number of theistic evolutionists and old earth creationists. He has already collaborated on refining the population genetics of such a proposal, and is exploring it further in another book, for the benefit of both science and the church at large. The GAE paradigm can even be useful for those who take certain Young Earth positions.

In partial contrast, Generations is deliberately written as a first example of how GAE may be used to make deliberate choices, to present a particular application to the interpretation of Scripture and, specifically, to build a biblical theology from it. Any research programme is, in the end, only as useful as the specific results it achieves by closing down options. Needless to say, I hope others will find my ideas a useful contribution.

But from another angle, I retain the same intention in my book as Joshua Swamidass does in his – to demonstrate that the paradigm itself is widely useful. So even if none of my conclusions take root, the book will have done its job if it suggests to others how they might use the lens of GAE for their own, more worthy, work.

If Adam and Eve really were historical figures living in relatively recent times, then their story in Scripture will have been based, like the rest of biblical history, on genuine traditions, and not on inspired myth-making. It is akin to the difference between handed-down memories about George Washington, and a mythical figure like Uncle Sam. The truth of the first depends on the accuracy of transmission, whereas the latter is an expression of perceived national character – a different kind of truth.

Assuming such a well-known tradition, it is very likely that the original author of Genesis would have been fully aware of Adam and Eve being “special” people living within an already existing human race; furthermore, that he will have written his book on that basis, rather than on the traditional Christian assumption that Adam and Eve were the first rational couple in a brand new world. He would, perhaps, feel under no more obligation to reinforce the particular historical background of his source than a modern writer would have to point out that Washington was, indeed, the first American President (or that Uncle Sam was not!). Readers in the distant future might miss the distinction, without some clues as to the kind of world America represents. In my view, genealogical science is just such a big clue for us about Genesis.

What is the significance of genealogy in the creation story?

What is the significance of genealogy in the creation story?

I spend some time in Generations discussing why genealogy matters at all. Historically, the doctrines of both the unity of mankind (positively) and the transmission of original sin (negatively) have depended on descent from Adam both in the Augustinian (Western) and the Irenaean (Eastern) traditions.That alone would be sufficient reason for offering GAE to the church, as David Opderbeck realized when he first presented the idea.

Another partial explanation is that the Bible itself lays enormous stress on the concept of genealogy, and (as I explore in the book) deals with this in relational terms both of biological descent and, interestingly, adoption. Many significant meanings can be investigated in the Bible once one frees oneself from modern science’s stress on genes and inherited traits and thinks more as the ancients thought.

Indeed, it is arguably genealogy that is the entire basis of history, which is important if the Bible is to be seen as a record of primarily historical dealings between God and humankind. History deals with peoples, nations, inherited culture, dynasties of power and so on, all of which ultimately arise from family relationships. It is not only under modern capitalism that “family” is crucial.

Do people outside the Garden challenge traditional theology?

Is the presence of people outside of the Garden a challenge to traditional narratives of creation? What is your case that this could be both Scripturally and theologically sound?

The Genesis 1 account of the creation of people occurs entirely outside the garden! To me, the story of Adam isn’t a creation account at all, but a commissioning rather like that of other biblical pioneers like Abraham. Adam originates out in the natural world, and is placed in the garden, a special, spiritual place. The creation story is told in a literary, “mythic” way, but surprisingly little of the following chapters, though also stylized and poetic, reads as an “Uncle Sam” myth, but rather as “George Washington” history.

Incidents like the talking snake seem magical, rather than mythical, but even that could be a misunderstanding. Old Testament scholar Mike Heiser has made a strong case that the serpent (nachish) would have been understood as a member of the divine council, so that speech – and an appearance of authority – would be expected, if supernatural. There is no doubt that the New Testament consistently identifies the serpent with Satan.

I see the creation account as a short, a-historical preface to the Bible’s action, beginning at Gen 2:4, from which comes the book’s title. Specifically, I take Genesis 1 as a phenomenological account of the world structured, as much mainstream scholarly opinion now holds, as a temple-building narrative, showing that the universe is the temple God built for his own worship. That seems theologically absolutely orthodox to me.

Adam, in the context of Genesis, is primarily the fountainhead of the line that became Israel, and so is a figure in their history. But there is also a hint of universalism, notably in the Table of Nations of Genesis 10, which becomes central to Paul’s New Testament understanding in Rom 5, and is shown to be scientifically possible through the Genealogical Adam and Eve. Nothing has changed theologically, but the theology now connects directly to the world of history and science.

If we assume, for a moment, that an Eden narrative received by a historical tradition would, from everything we know from secular knowledge, take people outside the garden for granted, then we begin to discover that those people are implicit in the text itself. The assumption is also consistent with the well-known literary parallels to Genesis in the Ancient Near eastern literature (ANE). We should not forget that these accepted parallels, including such sources as Atrahasis and Eridu Genesis, are from the very earliest stratum of human literature. Their existing texts date from the early second millennium BCE which, as archaeologist Kenneth Kitchen argues, is also the most likely time for the composition of the tradition that Genesis embodies.

This means that Genesis is neither derivative from, nor the direct source of the ANE parallels but an equally valid parallel tradition which, like the others, may well have its earliest literary roots in the mid-third millennium. All these accounts may well reflect actual events passed down in oral form for a quite plausibly short period before this. The ANE sources give some useful clues about why Genesis would express such a reality in the ways it does.

There are other such clues to be found in disciplines such as the history of languages, ethnology, ancient cosmology and paleogeography, which I tap in order to consolidate a picture of the kind of world Adam and Eve would have inhabited and, just as importantly, the kind of world that the writer of Genesis knew.

Why does it matter to place the Eden account into real history?

Why does it matter to place the Eden account into real history?

The most important contribution of the book, in my opinion, is that by placing the Eden account into a real history – by which I mean the account of history shared by the rest of humanity in its studies – the “big story” of the Bible, nowadays often called its metanarrative, can be seen to be rooted into a gritty reality from its very beginning. The stark historical truths central to Christianity – the cross and resurrection of Jesus – are the solution to the stark historical problem described in the early chapters of Genesis. The whole Bible is describing God’s active intervention in human history to solve a particular historical problem, which is of course what traditional Christianity has always taught in its concept of “salvation history.”

There is now an increasing body of scholarly literature showing how this story is inherent within the authorial intent of the biblical writers from Genesis onwards. In my book, I draw particular attention to the work of John Sailhamer, Greg Beale and Seth Postell, but even whilst my book was at the publisher, Kevin Chen produced a new study focusing on the Messianic themes in the Pentateuch.

Interpreting those early chapters through the lens of the GAE paradigm significantly clarifies the nature of both the problem and its solution in Christ. For example, the Table of Nations of Genesis 10 shows more clearly the surprisingly universalist tone of Genesis when seen as the local spread of an Adamic line rather than the expansion of the human race.

Adam is no longer the first man, but a new kind of man called by God from amongst mankind on behalf of mankind. This closely resembles other figures like Abraham, Moses, and even Jesus himself who, though uniquely the Incarnate Son is also God’s chosen from amongst mankind on behalf of both Israel and the whole of humanity in Adam. The salvation of the whole human race, then, is not a Gentile corruption of the national religion of the Jews, but a theme that goes back to the very beginning of Genesis.

What is the difference between the old and new creation?

In your book, you make a strong distinction between old creation and new creation. What is the difference, and how are they connected to each other?

Space prevents me describing in full here some of what I consider the most interesting specific proposals of Generations. For example, applying GAE to the “temple imagery” noted in Genesis by John Walton, Greg Beale, Richard Middleton and others casts significant new light on the genre and literary purpose of the Genesis 1 creation account, showing how, properly understood, it should never have been thought to conflict with science. Keeping in view the two creations also answers the objections raised by some scholars against that temple imagery, by showing that the biblical authors were consciously writing about two patterns of temple – one corresponding to the old physical creation of Genesis 1, and one to the new spiritual creation which, contrary to our common assumption, was intended to be inaugurated through Adam and Eve in the garden.

The most far-reaching conclusion I draw from the strands of evidence enabled by the GAE paradigm is that the whole Bible is all about the new creation (though Greg Beale has come to much the same conclusion apart from GAE in his New Testament Biblical Theology). That relieves the tensions with historical sciences, but more importantly changes the whole way we approach the Bible.

What is the painting on the cover of your book?

The cover of your new book is a painting depicting the risen Christ releasing captive souls from sin and death, starting first with Adam and Eve. What is the meaning of this painting, and how does it relate to the overall message of your book?

We used a traditional painting for the cover of my first book, which is about the first, “natural” creation. Generations is really about how the new creation begins in Eden, so it seemed right to use another traditional image to show the two books as an “Old and New Testament.”

In God’s mind, the Fall was already closely linked to his eternal purposes in Christ. This idea is not really represented strongly in traditional Christian imagery, but the common mediaeval theme of the “harrowing of hell” illustrated on the cover, in which the risen Jesus comprehensively undoes the work of Satan by liberating the dead, links Jesus with Adam nicely.

The fact that the demons in the image somewhat resemble Australopithecines is purely coincidental – they do not represent the fully human people outside the garden!

References

- http://potiphar.jongarvey.co.uk

- https://peacefulscience.org/books/gods-good-earth/

- https://peacefulscience.org/books/generations-heaven-earth/

- https://peacefulscience.org/books/genealogical-adam-eve/

- http://potiphar.jongarvey.co.uk/2020/02/17/a-retrospective-on-my-last-decades-work

- https://biologos.org/articles/a-historical-adam

- https://peacefulscience.org/

- http://potiphar.jongarvey.co.uk/category/genealogical-adam

May 14, 2020

Mar 26, 2021

Mar 10, 2026