I am one of the scientists studying phosphine in the clouds of Venus. We wonder if this might be the first signs of life on another planet. The scientific debate is growing as we wonder.

We have not yet sorted this all out (see here and here). So, in this article, I want to explain my perspective1 on how this is all unfolding.

A dip at 1 mm

In 2017, my colleague Jane Greaves (University of Cardiff) saw something unexpected. She used the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope (JCMT) to look for a dip in the light from Venus at 1 millimeter (mm) wavelength.

Light that shines at 1 mm is made up of photons with the energy of about 5/4th’s of a milli-electron-volt. Warm bodies like you or me produce these in abundance. These particular photons were produced by the heat of the clouds of Venus. Greaves was looking at 1 mm because a molecule called phosphine (one phosphorus atom bound to three hydrogen atoms, or PH~3~) absorbs light at that wavelength.

She had read several academic papers demonstrating that on Earth, phosphine is produced exclusively by life. This made her wonder if it could be a remotely detectable biosignature, and determined to look for it in the clouds of Venus, our sister planet.

But why Venus?

Venus seems to be a negative control in the search for life on other planets. The clouds of Venus are thought to be made of very concentrated sulfuric acid. Our stomach acid is mild by comparison. Venus also has far less available water than the most arid desert on Earth.

Greaves did not think life would proliferate in the clouds of Venus, so she anticipated that no signs of life would be detected there. She thought that the search for phosphine on Venus would turn up empty.

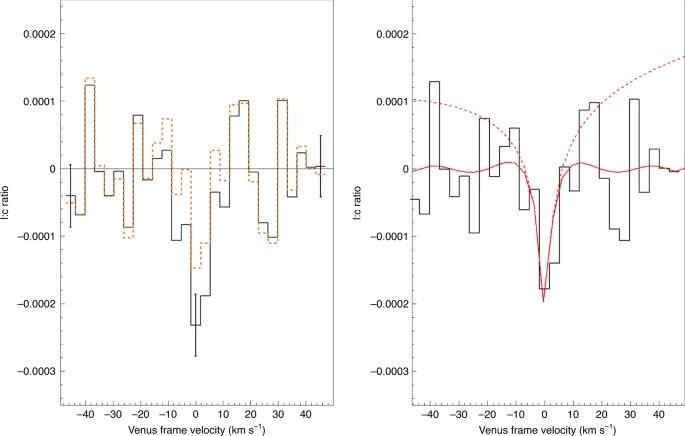

She was very surprised when, instead of a flat line, she saw this 1 mm dip, exactly where she predicted to phosphine would show up. Her negative control was not a negative. Now what?

She asked me to join the project, and other experts from MIT.2 I was to use a computer model of the Cytherean atmosphere to cross check that this dip at 1 mm really corresponded with phosphine.

We were considering all the other explanations for this dip. Perhaps there was some error in the JCMT which collected the data. Then, more than two years later, the same 1 mm dip was seen with a different telescope, the Atacama Large Millimiter/submillimeter Array (ALMA). The anomaly, whatever it is, was not in our telescope.

We decided to write these results up, both the detection and a very long paper considering and ruling out all known non-life sources of phosphine in the clouds of Venus. That sparked a debate that is still ongoing.

These are the major claims of scientific papers, taken together:

- There is a feature at 1 mm that was seen by JCMT

- The same feature was seen by ALMA

- The only known molecule that can explain this feature is phosphine

- Therefore, phosphine is in the clouds of Venus

- The phosphine abundance is estimated around 10 ppb3

- No known abiotic source of phosphine is sufficient to explain the signal.

- Known biotic sources can explain the signal if they are as productive on Venus as on Earth.

Most of these claims have been challenged. I walk through some of the papers that challenge these, the Greaves et al. replies, and my personal assessment of where things stand.4

Is the dip real?

The ALMA identification has been challenged by multiple groups, including one group lead by Ignas Snellen (University of Leiden) in 2020 and the other by Alex Akins (JPL) in 2021. Greaves et al. (2021) replied to them. Several scientists were unable to recover the 1 mm feature in the ALMA data, and Akins et al. claim such a signal is unlikely to be recoverable because of the distribution of the molecule in the atmosphere of Venus and the way ALMA observes the planet. But Greaves et al., in their 2021 reply, were able to recover the ALMA signal using several different methods.

As far as I am aware, no group other than Greaves et al. has been able to recover the ALMA signal. So, there is still a disagreement here.

The JCMT observations were also challenged by Mark Thompson (Hertfordshire & Leeds) in 2021. In his re-analysis of the data, he cannot see the 1mm dip. The reply from Greaves et al. (2021) uses a method similar to those of Thompson and does recover the feature. Other groups have also been able to recover the JCMT feature.

It seems unlikely that the disagreements about this one ALMA data set will be resolved by argument alone. More observations will be needed to sort this out. At the same time, it seems presence of the 1 mm dip in the JCMT data is generally accepted by radio astronomers.

Is phosphine causing the dip?

So, the 1 mm dip in the JCMT data is probably real. But is it phosphine?

The same group as Akins et al. claim that sulfur dioxide could be the cause. This is a molecule known to be present in Venus’s atmosphere, and it is not a signature of life. (Lincowski et al. 2021).

If the ALMA signal is also real, this would rule out sulfur dioxide. If sulfur dioxide produced the 1mm dip, it should produce other dips at different wavelengths. These other dips were not observed.

But maybe the ALMA signal is not real. In that case, sulfur dioxide is a possible explanation for the 1 mm feature, and there significantly more sulfur dioxide than we expected (Greaves et al. 2021).

Of course, it could be another molecule altogether causing this dip.

Where is the dip exactly?

Lincowski et al. (2021) didn’t simply propose that sulfur dioxide can explain the 1 mm feature. They demonstrate that the 1 mm dip can be traced to several kilometers above the top of the clouds. At the same time and in contrast, Terese Encrenaz (Observatoire Paris-Site de Meudon) looked for phosphine using a different instrument,5 and found no phosphine at all at the top of the clouds themselves. Taking the analysis of Lincowski et al. (2021) in a way that is consistent with Encrenaz et al. (2020) seem to show that the 1 mm signal, if it’s phosphine, originates well above the cloud tops of Venus.

The Greaves et al. (2021) reply point out one alternative. Perhaps, vertical turbulence and winds are much more vigorous above the clouds than previously believed, carrying the phosphine above the clouds very rapidly. But this doesn’t seem consistent with other observations.

In my assessment, the best explanation for the 1 mm signal is that it originates above the clouds, not the clouds themselves, where we do not expect much sulfur dioxide or life. So, the 1 mm is caused either (1) by confusingly incongruent amount of sulfur dioxide above the clouds6 (2) or by some unknown molecules, (3) or by phosphine above the clouds.

The Inference to Life

Is there life in the clouds of Venus? The inference to life would rest on the claim that phosphine was seen in the clouds of Venus. Greaves et al. and Bains et al., did not reason “we don’t know what the 1 dip is, therefore life.”

On the contrary, the authors of both of these papers considered all known explanations including life as we know it. They found that only life as we know it was sufficient to provide 10 ppb concentrations of phosphine in the clouds.

This claim is falsifiable. It might even have already been falsified. If there’s phosphine above the clouds, the source required to produce the phosphine far exceeds what non-life or life as we know it can do! Some completely unknown chemistry would be required to explain phosphine that high in the atmosphere.

Maybe there is life in the clouds of the Venus; the 1 mm dip may not qualify as evidence of it.

Why not? Because the signal itself probably is from far above the clouds of Venus, not the clouds themselves, where it cannot be explained by life as we know it.

Something strange in the clouds of Venus

There is still something strange up there. There is a mystery to untangle, and this mystery renewed broad popular interest in Venus.

It has also inspired the planetary science community to return to data from the Pioneer Venus mission, the only US probe to enter into Venus’s atmosphere and characterize its composition.7 Rakesh Mogul (California State Polytechnic University) lead a project that reanalyzed the data, published in 2021. They found signs of phosphine and evidence of other unexpected chemistry: ammonia, methane, hydrogen sulfide.8 In addition, an unknown compound is present in the clouds absorbing ultraviolet light, and its distribution in the clouds is patchy.

My own interest in Venus was initially very narrow; focused just on providing context for the phosphine detection. Over the two years that our team worked on the project, my fascination with the planet grew. I quickly realized how little is actually known about our evil twin, the puzzle of its atmosphere,9 and what might be hiding within its clouds.10

There is certainly some strange and unknown chemistry is going on in the clouds!

The best current models leave many questions unanswered. I’ve given my take here, but many observations of Venus remain baffling. And now two new NASA missions (DAVINCI+ and VERITAS) and one ESA mission (ENVISION) have been approved this summer, and JAXA and ROSCOSMOS also considering joining in the fun.

I am hopeful that we’ll find out whether life’s affecting the chemistry of Venus’s clouds during my lifetime. It would be satisfying to know the answer either way. I just want to know what’s going on in those clouds!11

References

Akins, A.B., Lincowski, A.P., Meadows, V.S. and Steffes, P.G., 2021. Complications in the ALMA Detection of Phosphine at Venus. The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 907(2), p.L27.

Baines, K.H., Nikolić, D., Cutts, J.A., Delitsky, M.L., Renard, J.B., Madzunkov, S.M., Barge, L.M., Mousis, O., Wilson, C., Limaye, S.S. and Verdier, N., 2021. Investigation of Venus Cloud Aerosol and Gas Composition Including Potential Biogenic Materials via an Aerosol-Sampling Instrument Package. Astrobiology.

Bains, W., Petkowski, J.J., Seager, S., Ranjan, S., Sousa-Silva, C., Rimmer, P.B., Zhan, Z., Greaves, J.S. and Richards, A., 2021. Phosphine on Venus Cannot be Explained by Conventional Processes. Astrobiology. arXiv:2009.06499.

Bierson, C.J. and Zhang, X., 2020. Chemical cycling in the Venusian atmosphere: a full photochemical model from the surface to 110 km. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 125(7), p.e2019JE006159.

Bougher, S.W., Hunten, D.M. and Phillips, R.J. eds., 1997. Venus II–geology, Geophysics, Atmosphere, and Solar Wind Environment (Vol. 1). University of Arizona Press.

Encrenaz, T., Greathouse, T.K., Marcq, E., Widemann, T., Bézard, B., Fouchet, T., Giles, R., Sagawa, H., Greaves, J. and Sousa-Silva, C., 2020. A stringent upper limit of the PH3 abundance at the cloud top of Venus. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 643, p.L5.

Greaves, J.S., Richards, A.M., Bains, W., Rimmer, P.B., Sagawa, H., Clements, D.L., Seager, S., Petkowski, J.J., Sousa-Silva, C., Ranjan, S. and Drabek-Maunder, E., 2020. Phosphine gas in the cloud decks of Venus. Nature Astronomy, pp.1-10.

Greaves, J.S., Richards, A., Bains, W., Rimmer, P.B., Clements, D.L., Seager, S., Petkowski, J.J., Sousa-Silva, C., Ranjan, S. and Fraser, H.J., 2021. Recovery of Spectra of Phosphine in Venus’ Clouds. arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.09285.

Hunten, D.M., Colin, L., Donahue, T.M. and Moroz, V.I., eds., 1983. Venus. University of Arizona Press.

Lincowski, A.P., Meadows, V.S., Crisp, D., Akins, A.B., Schwieterman, E.W., Arney, G.N., Wong, M.L., Steffes, P.G., Parenteau, M.N. and Domagal-Goldman, S., 2021. Claimed Detection of PH3 in the Clouds of Venus Is Consistent with Mesospheric SO2. The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 908(2), p.L44.

Mogul, R., Limaye, S.S., Way, M.J. and Cordova, J.A., 2021. Venus’ mass spectra show signs of disequilibria in the middle clouds. Geophysical Research Letters, 48(7), p.e2020GL091327.

Rimmer, P.B., Jordan, S., Constantinou, T., Woitke, P., Shorttle, O., Paschodimas, A. and Hobbs, R., 2021. Hydroxide salts in the clouds of Venus: their effect on the sulfur cycle and cloud droplet pH. Planetary Science Journal. arXiv preprint arXiv:2101.08582.

Snellen, I.A.G., Guzman-Ramirez, L., Hogerheijde, M.R., Hygate, A.P.S. and van der Tak, F.F.S., 2020. Re-analysis of the 267 GHz ALMA observations of Venus-No statistically significant detection of phosphine. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 644, p.L2.

Sousa-Silva, C., Seager, S., Ranjan, S., Petkowski, J.J., Zhan, Z., Hu, R. and Bains, W., 2020. Phosphine as a biosignature gas in exoplanet atmospheres. Astrobiology, 20(2), pp.235-268.

Thompson, M.A., 2021. The statistical reliability of 267-GHz JCMT observations of Venus: no significant evidence for phosphine absorption. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters, 501(1), pp.L18-L22.

Links

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41550-020-1174-4

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Clerk_Maxwell_Telescope#/media/File:JCMT_on_Mauna_Kea.jpg

- https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/14/science/venus-life-clouds.html

- https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/08/science/venus-life-phosphine.html

- https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/biosignature

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scientific_control#Negative

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cytherean

- https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/pdf/10.1089/ast.2021.0001

- https://www.gemini.edu/sciops/instruments/texes-north

Aug 14, 2021

Sep 3, 2021

Feb 21, 2026