This article was original published in Cultural Encounters magazine (under a different title), in a themed issue on theology and story.1

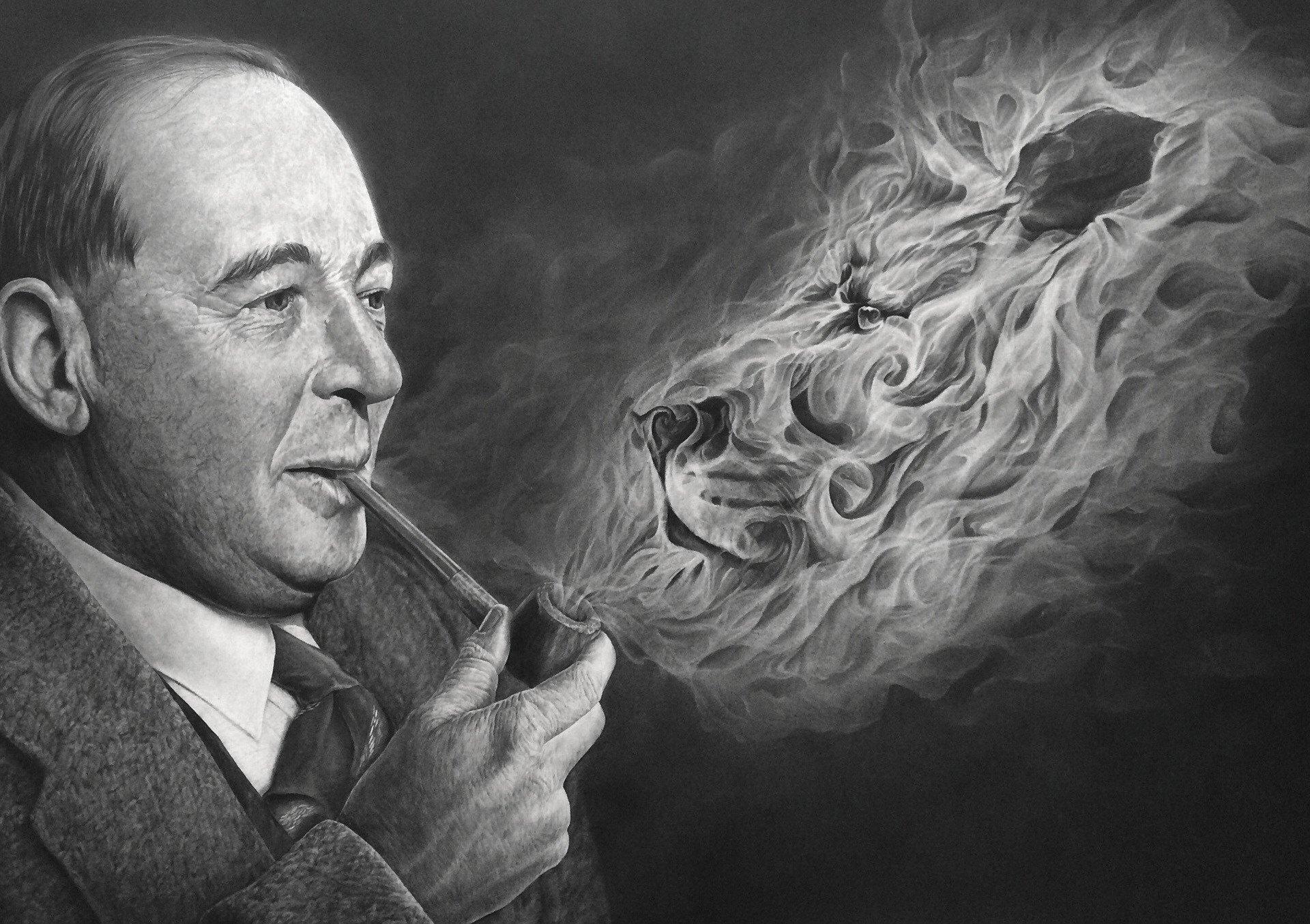

I first visited Boston as a graduate student. I was studying to become a scientist, a computational biologist. This is one of the great Meccas of the scientific world, through which almost every scientist passes at one time or another. The subways feature ads from local churches. They often included this quote from C.S. Lewis,

I believe in Christianity as I believe that the sun has risen: not only because I see it, but because by it I see everything else.

In 1954, Lewis wrote this as the final sentence of an essay titled Is Theology Poetry? The scientific world sees science as the only source of objective truth; theology is reduced to poetry. C. S. Lewis took a different view.

The waking world is judged more real because it can thus contain the dreaming world; the dreaming world is judged less real because it cannot contain the waking one. For the same reason I am certain that in passing from the scientific points of view to the theological, I have passed from dream to waking.

Traveling to a science meeting, this is a good thought for a graduate student to ponder. For Lewis, science was the dream, and theology was the waking world. Theology makes sense of everything, but science is limited, unable to explain even itself. Science is our world’s light, but Lewis found a greater light: so coherent that it illuminates everything else. This light guides his understanding of science, art, morality, and other religions.

Intelligent Aliens

What if we discovered intelligent life on other planets?

At the moment, science has found no hints of intelligent aliens. For now, it seems we are alone in the galaxy, and maybe the universe. We are, nonetheless, rapidly discovering and studying more and more planets orbiting other stars. What if we find signs of life on one of these planets? What if we found television transmissions from an alien planet, or one day they sent a space ship our way?

One way to respond to these questions is with defensiveness. On the one hand, we might be concerned how this would impact our understanding of Jesus. In Religion and Rocketry, C.S. Lewis explains,

The supposed threat is clearly directed against the doctrine of the Incarnation, the belief that God of God “for us men and for our salvation came down from heaven and was . . . made man.” Why for us men more than for others? If we find ourselves to be but one among a million races, scattered through a million spheres, how can we, without absurd arrogance, believe ourselves to have been uniquely favored?2

On the other hand, why not wonder in the mystery? The threat here, for Lewis, is merely “supposed.” In truth, the question of life on other planets is an invitation to theological imagination. How might we make sense of this in light of theology? With confident playfulness, he turns around the possibilities for the fun of it. Far from threatened, he relishes the imagination game to which the question calls him.

We do not know precise theological answers to these things. Instead we find mystery. In the mystery, we find wonder and it invites our imagination. Instead of clinging to a fragile theology unsettled by intelligent aliens, The Space Trilogy “imagined out loud” a vision of Jesus in a universe with life on other planets. Where some find an unsettling challenge to faith, C.S. Lewis found inspiration for his art.

The Multiverse and Fine Tuning

One of the most surprising things about the universe, it seems, is something called “fine tuning.” It seems that our universe seems fine-tuned for intelligent life. We have only one universe, it seems, so how did it become tuned? This, in a nutshell, is the Fine-Tuning Argument for God.

Scientists peered into mathematical formulas, studied radiation from space, and modeled black holes. From this vantage point, there seemed hints of another answer. Maybe there are many universes, in a grand multiverse, each one with different tuning. Maybe our universe is just the one that stumbled onto the right recipe for stars, planets, and intelligent life like us. Instead of an act of God, maybe fine tuning is an illusion. The multiverse is not proven, but it gives an alternate explanation, something other than God.

The apologist, the defender of the faith, is troubled. An argument for God is weakened.

Lewis, once again, takes a different way forward. He responds with theological fiction. The Chronicles of Narnia presents another view of the multiverse. Lewis imagines a wardrobe that, we find out, is a portal to another universe. The children enter in and find a world full of talking animals. Why were these children of Adam brought to another universe? “I am in your world,” said Aslan. “But there I have another name. You must learn to know me by that name. This was the very reason why you were brought to Narnia.”

Instead of grasping at fine-tuning arguments, Lewis embraced the multiverse with a vision of Jesus. Where apologetics was unsettled, Lewis spun a children’s tale.

Adam and Evolution

In our scientific world, we face another challenge. Evidence of evolution is becoming clearer in the genomic age. It really appears that we share ancestor with other animals. This, it seems, is how God created us. For many Christians, this is a challenge as threatening as intelligent aliens or the multiverse. Who then was Adam?

For over a century, most agreed that evolutionary science demonstrates that traditional theology of Adam is false. As surprising as this might sound, we were wrong. A scientific error was made in our understanding of how evolutionary science presses on our theology of Adam.

It turns out that, entirely consistent with the genetic and archeological evidence,3 it is possible Adam was created out of dust, and Eve out of his rib, less than 10,000 years ago, living in a divinely created garden where God might dwell with them. Leaving the Garden, their offspring blended with their neighbors in the surrounding towns. In this way, they became genealogical ancestors of all of us. Evolution, therefore, presses in a very limited way on our understanding of Adam and Eve, only suggesting, alongside Scripture, there were people outside the Garden.4

Science, even when it is correct, is limited. It cannot give us a complete account of the world. It cannot even tell us of Adam was de novo created or not. Evolutionary science, it seems, is silent about Adam. So, who was Adam?

Now we face a mystery. We do not know all the details; a very large number of scenarios are consistent with science and Scripture. What are the details? How could we know?

Facing a grand mystery, I fall into worship with creative curiosity.

I fall into the “theologized fiction” of C.S. Lewis. Wondering about the non-Adamic beings outside the garden, something seems surprisingly familiar. Marians, Narnians, or Neanderthals, they are all the same challenge to Adam. They, also, are the same invitation and inspiration to Lewis.

What is Our Light?

What light emanates uniquely from Christian thought? What illuminates the entire world more clearly than science? The answer should be obvious. Jesus Himself is this light (John 1:4-5,9; 8:12). He changes how we see the entire world. Through Him, everything else makes sense.

Faced with the challenges of science, instead of debating, maybe we could follow Lewis’ example. Just like us, C. S. Lewis encountering new ideas and ways to see the world. Rather than falling into unending arguments, he found another way. Finding a confident light in Jesus, he theologized stories that harmonized with science’s challenges.

Rather than insisting, “no, that is not true,” he playfully wondered, “if it were true, how might we see this in light of Jesus?” Our generation needs fearless creativity like this. Come let us worship with curiosity, imagining new stories of Adam that give a clear vision of Jesus to our scientific world.

References

- http://www.culturalencountersjournal.com

- http://www.samizdat.qc.ca/arts/lit/Theology=Poetry_CSL.pdf

- https://peacefulscience.org/books/worlds-last-night/

- https://amazon.com/dp/B00GR0CK1Y/

- https://amazon.com/dp/0064471195/

- https://www.jakeweidmann.com/products/the-untamed-lion

- https://archive.org/stream/worldslastnighta012859mbp/worldslastnighta012859mbp_djvu.txt

- https://www.asa3.org/ASA/PSCF/2018/PSCF3-18Swamidass.pdf

- http://henrycenter.tiu.edu/2017/06/a-genealogical-adam-and-eve-in-evolution

- https://afremov.com/lion-palette-knife-oil-painting-on-canvas-by-leonid-afremov-size-30-x24-75cm-x-60cm-11321642-offer.html

Jan 24, 2019

Oct 18, 2021

Mar 6, 2026