For decades, researchers have looked into the stereotypes associated with scientists. We are all familiar with this depiction:

The scientist is a man who wears a white coat and works in a laboratory.

Quite a bit of the details can change, of course.

He is elderly or middle aged and wears glasses. He is small, sometimes small and stout, or tall and thin. He may be bald. He may wear a beard, may be unshaven and unkempt. He may be stooped and tired. He is surrounded by equipment: test tubes, bunsen burners, flasks and bottles, a jungle gym of blown glass tubes and weird machines with dials. The sparkling white laboratory is full of sounds: the bubbling of liquids in test tubes and flasks, the squeaks and squeals of laboratory animals, the muttering voice of the scientist. He spends his days doing experiments. He pours chemicals from one test tube into another. He peers raptly through microscopes. He scans the heavens through a telescope [or a microscope!]. He experiments with plants and animals, cutting them apart, injecting serum into animals. He writes neatly in black notebooks. (excerpt from Mead and Metraux 1957 study)

But can the scientist be a woman? Rather, do we ever picture the scientist as a woman?

In 1983, David Wade Chambers and colleagues devised the Draw-a-Scientist Test (DAST), which was initially intended to map when a ‘standard’ image of a scientist begins to appear in a child’s consciousness. The study, involving nearly 5000 children from kindergarten to grade five in Canada and the U.S., revealed an incredibly low proportion of women scientists represented in children’s drawings – only 28 – and all of which were drawn by girls.

After about 5 decades and 78 similar investigations, David Miller and colleagues followed-up on this work by conducting a meta-analysis to see whether there is any progress in the depiction of gender diversity in scientists. They discovered that the tendency for children to draw a male scientist has decreased over time in the United States. Yet in spite of this improvement, the gender proportion was still far from parity. Children still drew more male than female when it comes to scientists.

The high association of scientists to a male figure is not so surprising. After all, that is what the popular culture often portrays (think Frankenstein, Jekyll, or Spock). Yet, such imbalance in gender representation has an important consequence. The masculinity associated with maths and sciences is a reason there are so few women in STEM.

A study involving high school students in Switzerland suggests that students’ perception of the gender image in chemistry, physics, and maths would later affect their decisions to enroll in a STEM program at a University level. The notion that maths and science are masculine subjects, therefore, prevented young women from choosing a STEM career. Gender stereotypical perception, not only affects how a child sees who could be a scientist, it impacts who ends up becoming a scientist.

We are faced with a chicken-and-egg situation. Less women in STEM means less female students aspiring a career in STEM, which results in very few female scientists overall.

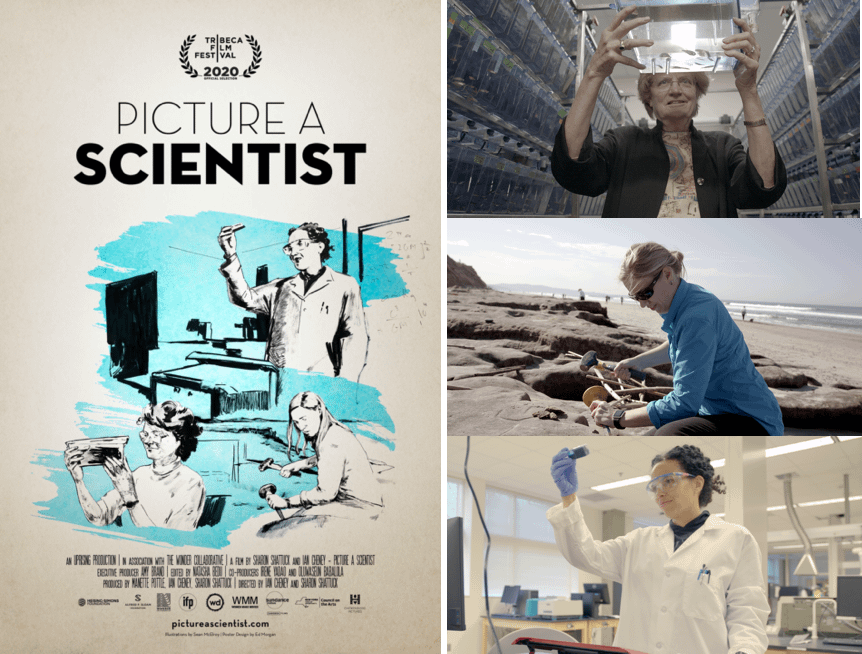

Some of the most startling and heart wrenching images of gender disparity in science, was aptly captured in the recent documentary ’ Picture a Scientist’. The film, which was selected for the 2020 Tribeca Film Festival, unpacked the pervasive layers of gender discrimination in academia through the personal accounts of three high-profile female faculties (biologist Nancy Hopkins, chemist Raychelle Burks, and geologist Jane Willenbring). What may be striking but not surprising, is that their professional credibility, status, and achievements did not eliminate the discrimination against them.

The narrative of the film centered upon the theme of sexual harassment, as explained throuh the iceberg analogy. At the top of the iceberg are the more explicit cases such as sexual coercion and assaults. These are cases that often get the attention. 90% of the cases, however, are lying beneath the surface. From vulgar name-calling, belittlement, and put-downs to being sabotaged from professional opportunities. This film unveiled horrid stories of talented women being reduced to a lesser human, as if they did not belong. In an environment where complaints were disincentivized, many were left without a choice but to endure the harsh treatment or to give up their dreams.

The President of Wellesley College, Dr. Paula Johnson, explained that

“right now we have a system that is built on dependence, really singular dependence of trainees whether they are medical students, whether they are undergraduates, or if they are graduate students on faculty for their funding, for their futures. And that really sets up a dynamic that is highly problematic. It really creates an environment in which harassment can occur”.

Because of this reason, a junior scientist (who is not on tenure), often felt unable to stand up for themselves for fear of career sabotage.

But there is hope. The light-at-the-end-of-the-tunnel appeared as these women began to take actions over these cases. Nancy Hopkins and a few other women at MIT went on to compile the 1996 MIT report, shedding light onto the gender discrimination in different departments. Jane Willenbring filed a Title IX complaint against David Marchant in 2016 leading to his termination. Raychelle Burks continues to advocate for women and underrepresented groups in sciences. Their message was clear, that silence is not a viable option.

The courage, determination and perseverance of these three women were remarkable. Their stories show that the fight for justice requires a concerted effort. The voices of both male and female allies and those in authority are crucial.

While the efforts paid off, the journey towards gender equity in science continues.

Today, many initiatives have been put together to ensure that women scientists are treated equally. Women can find support through organizations such as the Association for Women in Science and Women in Bio. Initiatives like Scientist Spotlights and IF/THEN Collection were established to encourage school teachers to introduce diversity in the classroom and inspire young girls to pursue STEM careers.

While substantial progress has been made, continuation is needed to ensure that the effort does not stall. The story captured by Picture a Scientist is a wake up call for all of us. It exposes the implicit biases we are all predisposed to believe. In order to look beyond the lab coats, test tubes and masculinity, real actions are needed on everyone’s part.

Let’s all hope that someday in the future, we will picture the scientist as a woman.

The drawings in this post are from this article about drawing scientists.

References

- https://www.futurity.org/draw-a-scientist-gender-1714512

- https://science.sciencemag.org/content/126/3270/384

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/sce.3730670213

- https://srcd.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/cdev.13039

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Victor_Frankenstein

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dr._Jekyll_and_Mr._Hyde_(1887_play)

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spock

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2019.00060/full

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2019.00060/full#h8

- https://www.pictureascientist.com

- https://tribecafilm.com

- https://biology.mit.edu/profile/nancy-hopkins

- https://www.american.edu/cas/faculty/burks.cfm

- https://earth.stanford.edu/people/jane-willenbring

- https://www.nap.edu/visualizations/sexual-harassment-iceberg

- http://web.mit.edu/fnl/women/women.html

- https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/tix_dis.html

- https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2017/10/disturbing-allegations-sexual-harassment-antarctica-leveled-noted-scientist

- https://susnano.wisc.edu/2020/06/29/raychelle-burks-scholar-in-residence

- https://www.awis.org/about-awis/awis-history

- https://www.womeninbio.org

- https://scientistspotlights.org

- https://www.ifthencollection.org

- https://www.pnas.org/content/117/13/6990

Feb 2, 2021

Mar 30, 2021

Feb 25, 2026