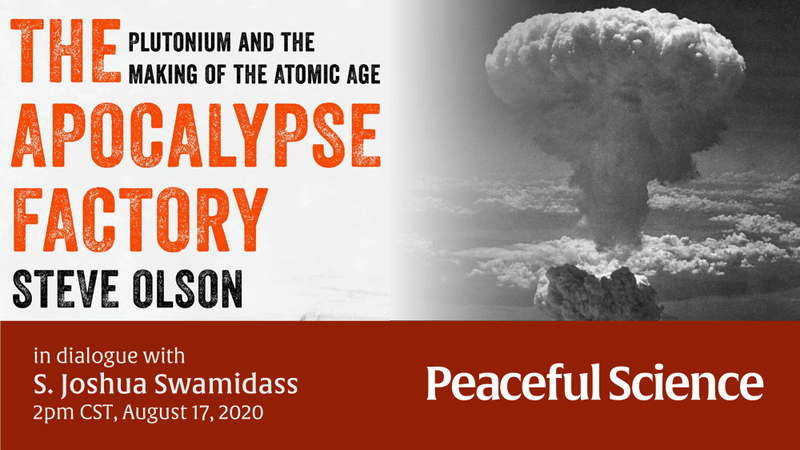

On August 17, 2020, Steve Olson is discussing his book on the nuclear bomb and the Hanford site: the factory refined plutonium fuel for the bombs. He is an award-winning science writer who just authored The Apocalypse Factory: Plutonium and the Making of the Atomic Age. He is also the author of Mapping Human History: Genes, Race, and Our Common Origins, which was one of five finalists for the 2002 National Book Award for Nonfiction.

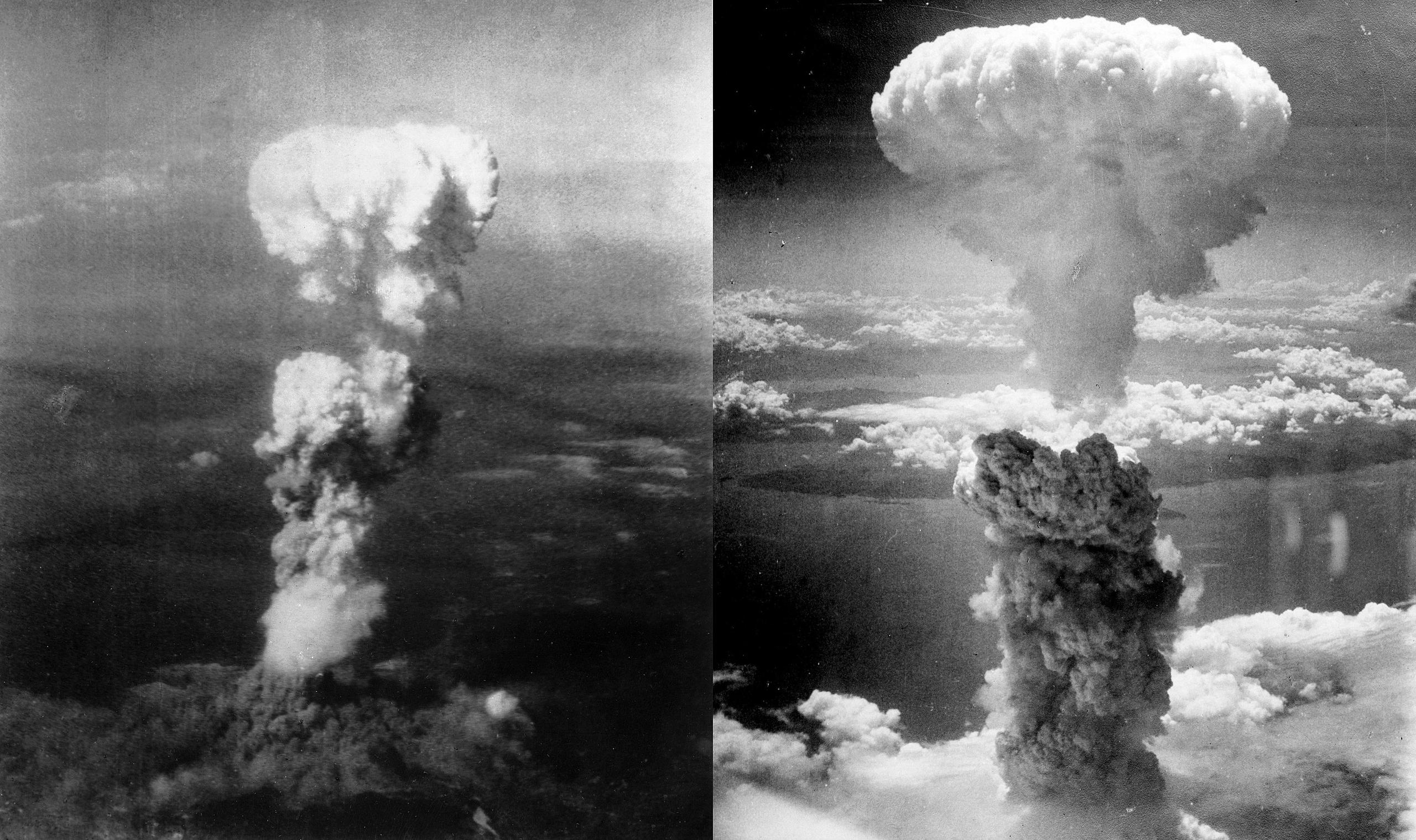

Seventy-five years ago today, on August 6, 1945, the first atomic bomb ever used in war was dropped on Hiroshima. A city was destroyed. Three days later, on August 9th, the second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. Another city destroyed. A war was ended, but at what cost?

What led us here? What was the aftermath? Seventy-five years later, what have we learned? What remains to be learned?

Nuclear bombs are a deep paradox. On the one hand, scientific progress was seen as a white knight, the solution to all the world’s problems. The scientific discovery that uranium atoms split was riveting at the time, and landmark in history comparable to the discovery of DNA’s structure. The mad dash to create the bomb before the Germans was inspiring. Nuclear power, only possible with the knowledge gained from bombs, still holds promise as a clean, cheap and plentiful source of energy.

One the other hand, scientific progress brought us into the age of nuclear war. We could now, for the first time, destroy the entire world, including ourselves. Scientists who created the bomb were immediately troubled by its moral implications. Would scientific programs save the world or destroy it? Would we have the moral discipline to hold back from Armageddon? Would the atom ever be harnessed for peaceful purposes?

Somehow we created enough bombs to destroy the whole world several times over, yet managed to avoid ending the world even once. Are stockpiles of nuclear weapons really the picture of peace?

Could nuclear power ever provide safe power for the world? How do we clean up the thousands of tons of nuclear waste given to us by prior generations?

These are sorts of questions that this anniversary invites. Olson’s new book brings us here. He explains why he references the “apocalypse” in his book, alluding to original meaning of the term in the book of Revelations, the book of the apocalypse,

An apocalypse is a revelation — literally an uncovering — about the future that is supposed to provide hope in a time of uncertainty and fear. The plutonium from Hanford, which fueled the first atomic bomb ever exploded, in New Mexico on July 16, 1945, and the bomb dropped on Nagasaki three weeks later, revealed that the world had entered a new era. We still have not come to terms with that change.

In Revelations, it is Armageddon that destroy the world, but the revelation is meant to give hope with view of the future. The revelation includes prophecies of great suffering, but also that we will not be entirely destroyed. There are costs ahead, and pain we cannot avoid, but this need not end with our total destruction.

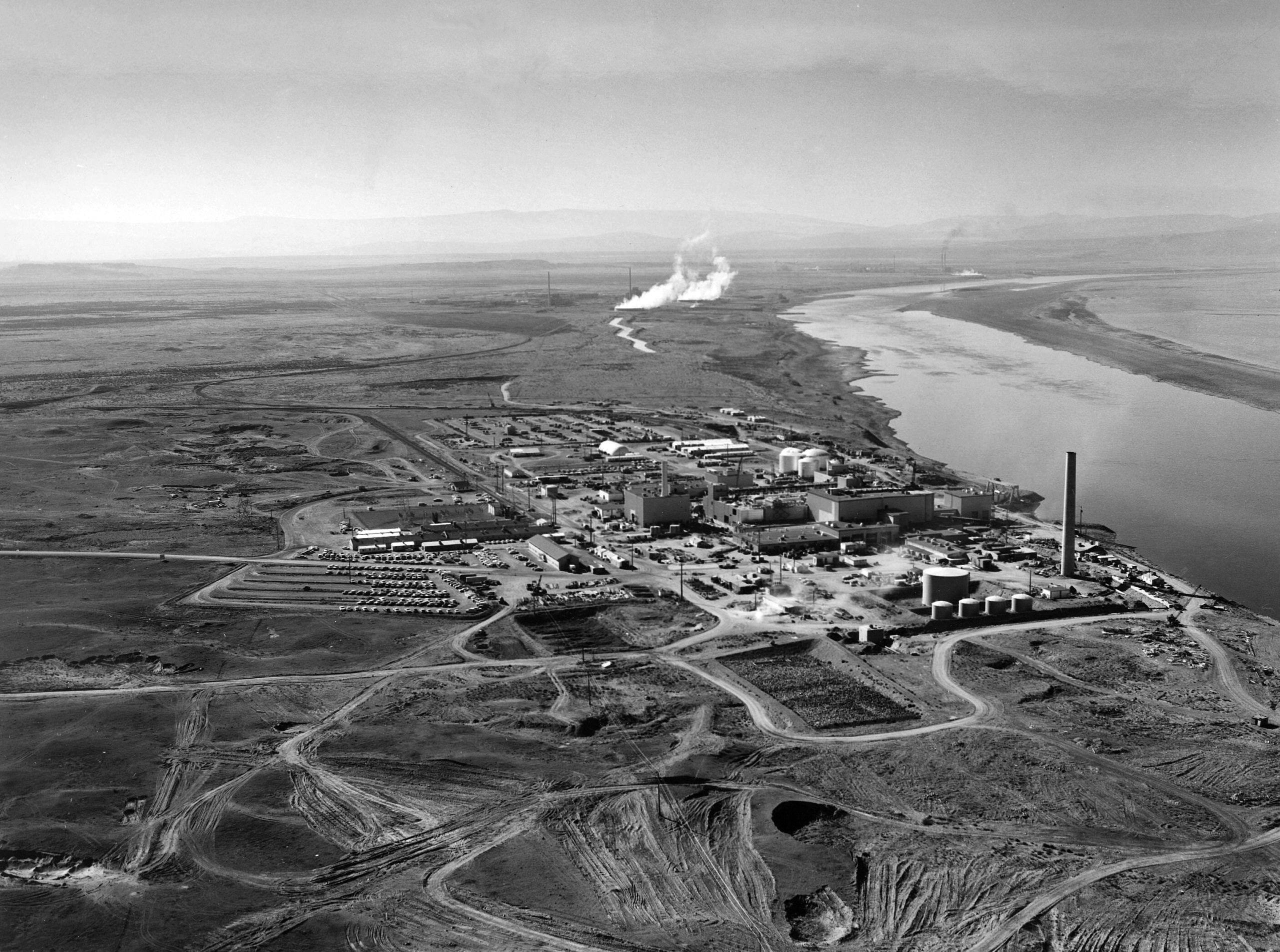

This brings Olson to the factory in Hanford, where lies a mess of nuclear waste that will require hundreds of billions of dollars clean and set right. This mess we inherit from our ancestors. Over seventy-five years, three generations have come and gone, none have cleaned the mess. We bequeath this toxic inheritance to future generations. The Hanford Site is a generational problem.

The history of the Hanford site teaches what we already know, but from which are quick to look away. We struggle with generational problems.

Our shared societal history of race and racism bring us to the same moral questions of inheritance. What do we do with the mistakes of our ancestors? How do we own their mistakes enough to fix them? While we aren’t responsible for the injustice done by others, we are responsible for perpetuating the unjust world we inherited. Do we have the hope, though, to remember our history and pay the costs of a just world?

The warnings by scientists of climate change also bring us to these moral questions. Do we have the hope and courage to see clearly what we might bequeath on future generations? How much cost can we bear give future generations a fair starting point go forward from?

In these ways, the story of the Hanford site brings us some of the most pressing questions of our moment.

This is much is certain. We live in a fallen world. Do we hope that God’s will might be done on earth as it is in heaven? Do we want a better way? Or is the world passed down to us good enough? generations that find a better way.

Olson’s book is important for helping us remember what faces us. It is a revealing book, exposing generational problems we should should know about, but have already forgotten. In teaching us our history, this book could also give us hope. The moral questions facing us at Hanford are just like those we are finding elsewhere. These questions call us to have courage in our moment, and they reveal our nature and our character.

At Peaceful Science we are thinking about questions of ancestry, which brings us to the moral questions of inheritance. We live in a world that we inherit from our ancestors, and we pass on this world to our own ancestors. We struggle to take responsibility for the problems bequeathed to us by our ancestors, and we struggle not to bequeath problems on our ancestors. This is, it seems, the human condition.

In view of the Hanford site, the apocalypse factory, what is the revelation for us?

Maybe our generation could be different. Maybe we could be good. Maybe we can be among the

References

- https://peacefulscience.org/books/apocalypse-factory/

- https://amazon.com/dp/0618091572/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atomic_bombings_of_Hiroshima_and_Nagasaki#/media/File:Atomic_bombing_of_Japan.jpg

- https://discourse.peacefulscience.org/t/_/4816

- https://discourse.peacefulscience.org/t/_/8589

- https://www.tri-cityherald.com/opinion/opn-columns-blogs/article244696607.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Columbia_River

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/N_Reactor

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/B_Reactor

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plutonium

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hanford_Site#/media/File:Hanford_N_Reactor_adjusted.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hanford_Site

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spent_nuclear_fuel

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hanford_Site#/media/File:Spent_nuclear_fuel_hanford.jpg

- https://peacefulscience.org/articles/definition-race/

Aug 5, 2020

Mar 9, 2022

Mar 13, 2026