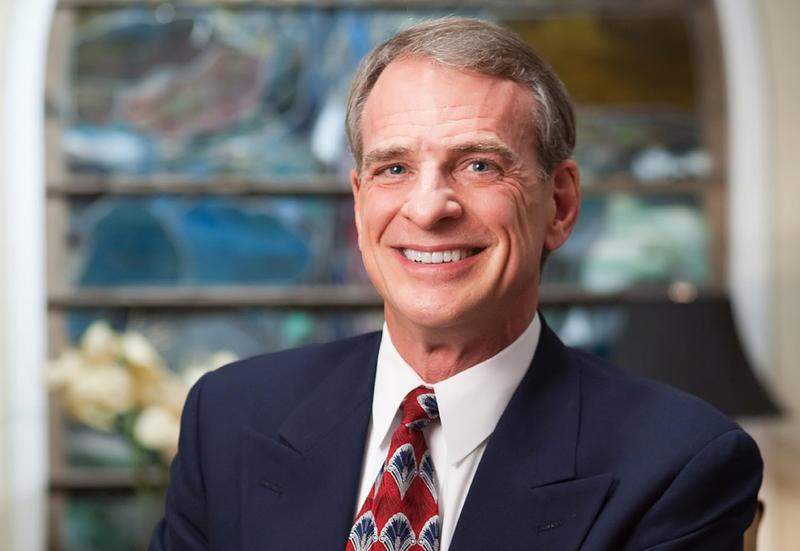

William Lane Craig is a philosopher, and a well-known apologist. But he is not anti-evolution. For years, Craig has argued that Christians can make space for the best science, including evolutionary science.

I wanted to be a scientist ever since I was in second grade. My father and I would watch documentaries about human origins, cavemen, and dinosaurs. I eventually gained an interest in meteorology, UFOs, and extraterrestrial life. By the time I reached my sophomore year of high school, I wanted to become an evolutionary biologist, studying either speciation or the evolution of tetrapods from aquatic life.

Meanwhile, I was also a devout Christian. My father was both a Baptist minister and a former professor of geomorphology. My parents encouraged critical thinking, and taught me that Christanity did not stifle science. Even though many of my childhood friends believed that Christianity and science were in conflict, I wanted to show them (and still do) that the conflict is only superficial.

Still, I was drawn towards anti-evolutionism from time to time throughout my childhood. It would sometimes come in the form of a Sunday school teacher telling me that we didn’t evolve from monkeys. Other times, I would hear a well-spoken evangelist warn of the moral consequences of evolutionary theory. These criticisms eventually became more sophisticated: “the scientific community has hastily inferred macroevolution from microevolution” and “bacteria remain bacteria, and dogs remain dogs.” All of these doubts made me question the scientific consensus, but I found an answer each time and fine-tuned my grasp of the science.

Even from a young age, the Genesis creation account struck me as poetic. The fact that the sun and moon were created on the fourth day seemed decisive against literalism (Gen. 1:14-19). Although I never doubted a historical Adam and Eve, I remained perplexed about their relationship to the rest of humanity given the science of human origins and the unexplained appearance of Cain’s wife in scripture (Gen. 4:17).

It didn’t help, however, when some Christians and science popularizers preach that evolution (or science in general) disproves religious belief. It made me constantly wonder if the fundamentalists had a point; perhaps the entire Christian message falls apart if the first few chapters of Genesis aren’t literal history.

These never-ending questions led me to be agnostic for a time in high school. Two loved ones had died from horrible diseases; one of them totally forgot who I was and the memories we shared. I then read more about the great extinction events in the history of life, the unstoppable march of death. I visited hospitals with my father when he would minister to the sick and dying. All of these experiences made me seriously question the goodness of God.

Although I was drawn to Christianity, I just could not reconcile the history of natural evil with God. And the idea that we once had it right in some Edenic paradise was painfully disappointing. There was some odd comfort, however, in believing that death and disease are simply the norm.

Dr. William Lane Craig, one of the world’s leading philosophers, was the first person I consulted after losing my faith. I submitted my doubts to the “Question of the Week” section of his website “Reasonable Faith.”

I had come to believe that evolution and the benevolent God of Christianity are hopelessly incompatible. In order to accept evolution, one must deny that the fall of man literally caused all death in the universe. But, if death has always existed, and is a necessary part of the evolution of life, then it appears as if one must ultimately accept that “God intentionally created the universe bad.”

I noted in my submission that,

…the evidence shows that humans evolved. That there was always death and suffering, that in every generation we have lived, we were afraid and alone in the universe.

I concluded with,

If there was no fall of man, what sin is there to save us from? If death had always been there because God created it to be, then how could man be blamed for anything? It didn’t make any sense.

To my surprise, I received a response soon afterwards from Craig himself. And he certainly schooled me.

Dr. Craig first noted that the problem of natural evil does not negate Christian belief. It is possible to reconcile these evils with (as are even anticipated by) the historical plausibility of the Resurrection of Jesus. After all, the resurrection would not have been necessary if death and calamity were not real problems. Thus, even if there wasn’t a historical Adam, we would still need to be redeemed of our individual sins.

But, one of the most important points that Dr. Craig explained was that faith (or any worldview really) should be understood as a web of interconnected beliefs. There are doctrines or beliefs central to the integrity of the web, whereas there are other beliefs that can be revised without collapsing the entire system. Dr. Craig wanted me to think more seriously about whether or not Genesis literalism is central to the web’s integrity, or if there are other plausible alternatives for the Christian.

He explained that,

At the core of the Christian web of beliefs lie such doctrines as the existence of God, the incarnation and resurrection of Jesus, the sinfulness of man, and so on. The reason you could not give up instead some minor belief like the scientific character or reliability of Genesis, but chucked Christian theism altogether, lies in your mistaken conviction that ‘the main core’ of the Christian worldview is ‘the fall of man,’ where the fall of man is apparently understood to imply, not only the doctrine of original sin, but also the origin of human disease and death as a result of human sinfulness. This is a horribly distorted view of Christianity.

I had never realized how rich and diverse the Christian tradition was on the question of death and natural evil. My own understanding of Christianity was terribly narrow, as Dr. Craig noted that

…the idea that human physical death and disease is the result of sin or the fall, though championed by Young Earth Creationists, cannot be found in the biblical text and is widely rejected by many committed Christians (including me).

Dr. Craig then offered one possible explanation for why God created a world with death already in it, and it was this paragraph alone that single-handedly made me rethink everything:

Perhaps God knew that a world of mortal creatures would be the most appropriate kind of place for a creature who would eventually fall into sin. It might be that such a universe is the best arena in which the human drama of God’s plan of salvation, including Christ’s death on the cross, would be played out. This world is a sort of vale of decision-making in which we mortal creatures determine, by our response to God’s initiatives, our eternal destiny. Suffering and death may not be the result of man’s sin, but it may anticipate man’s sin.

Dr. Craig was certainly arguing for the truth of Christianity. But he also gave me a path to a confident faith, unthreatened by the truth of evolution.

In that way, he opened the door for good science in my life too. He taught me to discern when scientists were stepping beyond the hard data and into the realm of philosophy—and when they were doing this well or poorly. He also helped me pay closer attention to when religious people were misunderstanding not only science but their own religious traditions. Rather than using the polemics of fear, Dr. Craig encouraged me to begin from a place of confidence and appreciate the nuances of both science and religion.

And, because of him, I was no longer settling for science popularizers. Instead, I consulted careful scientists who understood the limits of their expertise and welcomed rigorous philosophical and religious thought. I began to read other Christian intellectuals as well, including Dr. Craig, who had wrestled with these same questions and emerged more enthralled by God and His creation.

I eventually told Dr. Craig that my agnosticism had ended. I still had major doubts and sometimes toyed with deism. But, it was really the beauty of the Christian story, and the life of Jesus that made me realize that I am more than just a material object in an indifferent universe. I also came to realize that the leap to nihilistic atheism from evolution was not only unwarranted but simply one among many other interpretations.

Today, I am still a Christian. I am grateful to people like Dr. Craig and my parents who encouraged me to research my beliefs and skepticism, to be fair-minded, and open to the data of creation and scripture. They taught me to not be swayed by rhetoric but pay close attention to the facts, to discern interpretation from reality.

I ultimately learned that Christians do not have to strawman science, and scientists do not have to strawman religion. It hurts the cause of both sides to diminish the other, because both systems of thought can be highly sophisticated and contribute to a more complete understanding of reality. It has brought me joy to encounter Christians like Dr. Craig, whose scholarship encourages rather than stifles scientific thought. The “dogma” that atheists have a unique claim to science not only harms science but discourages the contributions of religious people whose reverence for God is precisely what inspires their study of the universe.

References

Oct 27, 2021

Oct 31, 2021

Feb 21, 2026