This article is based on an article first published at Southeastern Baptist Seminary (SEBTS), where Dr. S. Joshua Swamidass is currently a scientist-in-residence. The author, Aaron Ducksworth, is a doctoral student at SEBTS. He holds a B.S. in Interdisciplinary Studies from Mississippi State University, a M.Div., and a ThM in Theology from Southeastern. He is currently pursuing a PhD in Christian Ethics.

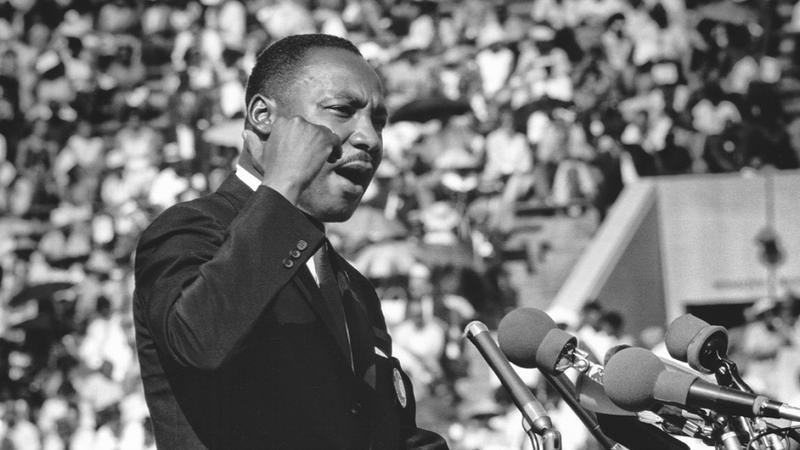

Martin Luther King, Jr. was one of the most impactful theologians of the 20th century, but most Christians have never read his work. And, when they do read his work, they often negatively misread him. So then, how should Christians read King?

Read King in his historical and socio-cultural context.

People are born into a socio-cultural context. It’s inescapable. Our context can shape us, positively or negatively, whether we know it or not, and whether we admit it or not. My history professor once expressed disdain toward theologians who ignored historical and socio-cultural contexts.

Nothing happens in a vacuum,

he explained, and history often tells us ‘why’ and ‘how’ theological ideas developed. For example, Kirk R. Macgregor argues that “World War 1 itself caused a crisis in Barth’s theology.”1 He posits that the willingness to “engage culture rather than separate from it as the fundamentalists” contributed to the birth of evangelicalism.2 Additionally, the Danvers Statement admits that the perceived “widespread uncertainty and confusion in our culture regarding the complementary differences between masculinity and femininity” led to the Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood.3

Failure to consider the socio-cultural context of a theologian and their work could adversely impact our understanding of their work. In a theology course, some of my classmates attempted to engage and interpret theologians’ work apart from the theologians’ context. On several occasions, my professor stopped the class and said, “I don’t think ‘X’ is doing that with their theological project;” and “I don’t think that was ‘X’s’ goal.”

For example, on one instance some of my classmates were trying to read a 20th century, Swiss, World War 1 impacted, ex-liberal, neo-orthodox, Trinitarian theologian, through their 21st century, American, peacetime, Reformational, conservative, evangelical, Christocentric lens. The problem wasn’t their 21st century vantange point. The problem was they failed to consider the 20th century socio-cultural context of the theologian, and how it shaped the theolgian’s terminology, theological formation, hermeneutics, theological commitments, etc. As a result, they misread.

To read King correctly requires an honest assessment of the socio-cultural factors—Jim Crow, lynch mob impunity, the Cold War, etc.— and how they shaped his context and, consequentially, his theology.

Read King, truthfully.

Before reading any theologian, it’s helpful to consider our own biases and presuppositions towards them and what we think he or she represented. We can do this by asking:

- What have I heard about ‘X’ that I have never confirmed as true?

- Have I ever made an unbiased and sincere effort to understand his or her work?

- Have I only learned things about ‘X’ from people (in my tribe) who dislike him/her?

To read King, truthfully, is to acknowledge that we may already have certain biases or presuppositions, whether positive or negative, about him and his work. Furthermore, we should also ask ourselves questions as we are reading like:

- Am I looking for specific ideas and buzzwords that support my presuppositions and biases?

- Am I making King say something he is not really saying? If so, why?

Reading King, truthfully, can be difficult since he didn’t fully ascribe to single theological system, and much of his ethical, theological, and philosophical ideas were revealed unsystematically through sermons and speeches. Although his PhD from Boston University was in Systematic Theology, he never published a systematic theology volume. Teaching and preaching about segregation, and seeking the eradication of racial, legal, and economic injustices consumed much of his time. To understand everything he believed on a single theological topic requires reading and listening to numerous sermons and speeches. Thankfully, the work of scholars and pastors like Rufus Burrow, Jr, Mika Edmondson, Keith D. Miller, and many others, as well as the Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project, has made King’s theology very accessible.

Truthfully, read King.

A (non-Southeastern) professor once critiqued my classmate’s sermon because it appealed to ideas espoused by King. While stumbling over his words, it became obvious my professor was unfamiliar with King’s work. Similarly, a friend once expressed great apprehension towards King. After I asked which aspects of King’s theology he disagreed with, he too stumbled over his words and gave no concrete answer. So, I asked,

Have you ever listened to any of his sermons or read anything King’s written?

Embarrassed, he softly said,

No.

My professor and my friend made definitive statements about a person’s work they’d never read. As Christians, we have an ethical obligation to represent people and their work truthfully, whether we agree with their conclusions or not.4 After all, don’t we want our ideas to be represented truthfully?5 To truthfully read King, is to ask:

- Have I actually taken time to read King’s work, or have I relied on soundbites (from people or social media)?

- Have I understood King’s ideas enough to agree or disagree with them?

- Am I engaging in slander or libel in my discussion of King?

It’s one thing if a person’s work, words, or actions are intentionally negative and divisive; however, if my retelling of a person’s life or work contains unwarranted claims and divisive language, then I have engaged in slander and violated the Christian ethic.6

Read King as an Image Bearer.

I remember talking to a former classmate who revealed he’d been reading Jonathan Edwards and claimed Edwards was the greatest American theologian to ever live. Since I’d just walked out of the library, he asked which books I checked out. I replied, “A book on Martin Luther King, Jr.”

His first response was,

Wasn’t he an adulterer?

To which I responded,

Didn’t Edwards own slaves?

His silence ensued.

His response to the fact that I was reading King baffled me, especially when I found out he’d never read any of King’s work. Yet, the primary element about King’s life he ‘heard’ and felt comfortable repeating without evidence was, for him at least, an alleged moral shortcoming. Furthermore, he critically raised questions about one theologian’s moral shortcomings, while uncritically singing praises of another. Questioning King’s personal morality was not the problem. In many situations questioning a theologian’s moral life can be fair, warranted, and helpful for understanding their life and theology. The problem was that his tone, facial expression, and body language while questioning King’s morality also suggested his reasons for not reading King’s work.

This ethical inconsistency occurs too often among Christians. Within some theological tribes, there is a tendency to use any reason, including ad hominem, to “other” those whose ideas are different and challenging, especially when their ideas are about race, cultural engagement, and societal transformation. This “othering” rarely remains at the level of peaceable disagreement; disagreement often turns into hostility, which is followed by villainization.

To be clear, one has the freedom to not read a theologian based on their moral and ethical misconduct. In fact, in some instances, this may be wise. However, some Christians read the works of theologians with moral shortcomings all the time without qualification.

For example, George Ladd was an alcoholic who emotionally abandoned his family.7 Martin Luther became extremely antisemitic.8 James P. Boyce owned slaves and theologically justified chattel-slavery.9 Karl Barth theologically justified his decades long affair and insisted his mistress move in with he and his wife.10

The list could go on and on because all people are sinners with blindspots.11 However, the frailty of humanity does not mean that we ignore sin. Rather, it means that we deal with it truthfully in the life of an individual or community, hold them accountable, and biblically call them to repentance (if they are still living of course). If they are no longer living, we should consider what lessons and precautions can be learned from their moral and ethical shortcommings. Furthermore, we should also pray for healing and restoration for all who have been impacted by their sins, while humbly praying for grace that we don’t commit the same sins ourselves. Helpful questions to ask when considering the humanity of a theologian are:

- Does my disagreement with ‘X’s’ ideas impact my view of their humanity? If so, why?

- Do I view ‘X’ as made in the image of God despite their moral shortcomings? If not, why?

- Am I holding ‘X’ and my intellectual heroes to the same moral and ethical standards? If not, why?

- Am I using ‘X’s’ ethical conduct as an excuse to not read their work, because I’m hesitant to wrestle with their ideas (especially their ideas about race and culture)?

Read King as one on a theological journey.

I’ve encountered people who were raised with certain beliefs, but as they journeyed through life, their beliefs changed (for better or worse). King was no different. King grew up in a traditional Fundamentalist church. However, as a preteen, Fundamentalism failed to satisfy his intellectual curiosity, and he began to battle doubts about the Christian faith. He recalled, “At the age of 13 I shocked my Sunday School class by denying the bodily resurrection of Jesus. From the age of thirteen on doubts began to spring forth unrelentingly.”12

Intellectually gifted and still battling doubts, King enrolled in Morehouse College at the age of 15. During his early coursework, he was introduced to Biblical Criticism which caused him to feel as if “the shackles of fundamentalism were removed” from his theological framework.13 However, he soon noticed that Biblical Criticism directly contradicted the Biblical stories he learned in Sunday school which increased his doubts. He remarked, “…more and more could I see a gap between what I had learned in Sunday School and what I was learning in college.”14 However, during his junior year, he took a Bible class taught by George D. Kelsey. King emerged from the course rooted in his faith with the assurance “that behind the legends and myths of the Book were many profound truths which one could not escape.”15 Through his relationship with Kelsey, and Morehouse president Benjamin E. Mays, King decided to devote his life to ministry and pursue seminary.

After college, King applied to Crozer Theological Seminary, one of the few institutions that accepted African American students. Although his early coursework was steeped in Theological Liberalism, he found certain doctrines and teachings problematic. He explained:

It was mainly the liberal doctrine of man that I began to question. The more I observed the tragedies of history and man’s shameful inclination to choose the low road, the more I came to see the depths and strength of sin… Moreover, I came to recognize the complexity of man’s social involvement and the glaring reality of collective evil. I came to feel that liberalism had been all too sentimental concerning human nature and that it leaned toward a false idealism. I also came to see that liberalism’s superficial optimism concerning human nature caused it to overlook the fact that reason is darkened by sin. The more I thought about human nature the more I saw how our tragic inclination for sin causes us to use our minds to rationalize our actions. Liberalism failed to see that reason by itself is little more than an instrument to justify man’s defensive ways of thinking. Reason, devoid of the purifying power of faith, can never free itself from distortions and rationalizations.16

As King progressed in ministry, he began to move away from some of his previously held Theologically Liberal teaching and critique it through the lens of Neo-Orthodoxy. However, he also took issue with Neo-Orthodoxy and never fully embraced it. King claimed:

In spite of the fact that I had to reject some aspects of liberalism, I never came to an all-out acceptance of neo-orthodoxy. While I saw neo-orthodoxy as a helpful corrective for a liberalism that had become all too sentimental, I never felt that it provided an adequate answer to the basic questions. If liberalism was too optimistic concerning human nature, neo-orthodoxy was too pessimistic. Not only on the question of man but also on other vital issues neo-orthodoxy went too far in its revolt. In its attempt to preserve the transcendence of God, which had been neglected by liberalism’s overstress of his immanence, neo-orthodoxy went to the extreme of stressing a God who was hidden, unknown and “wholly other.” In its revolt against liberalism’s overemphasis on the power of reason, neo-orthodoxy fell into a mood of antirationalism and semifundamentalism, stressing a narrow, uncritical biblicism. This approach, I felt, was inadequate both for the church and for personal life.17

Beyond Theological Liberalism and Neo-Orthodoxy, King also engaged the works of existential philosophers like Soren Kierkegaard, Fredrich Nietzsche, Jean Paul Sartre, Martin Heidegger, and Karl Jaspers, although he disagreed with many of their conclusions. He remarked, “All of these thinkers stimulated my thinking; while finding things to question in each, I nevertheless learned a great deal from study of them.”18 As a committed Christian, King recognized “the ultimate Christian answer is not found in any of these existential assertions, [although] there is much here that the theologian can use to describe the true state of man’s existence.”[^19]

Many Christians fail to realize King was on a theological journey and only emphasize theologically liberal ideas he espoused during his M.Div. However, King’s writings included affirmations and critiques of Fundamentalism, Theological Liberalism, Neo-Orthodoxy, Existential Philosophy, Personalism, and Christian Realism. Since no single theological system in his context proved capable of eradicating racism and segregation, as he journeyed through life, he adopted ideas from various systems in hopes of achieving the Beloved Community and bringing justice, freedom, and dignity to African Americans. King’s life ended tragically at the age of 39 when he was assassinated in Memphis while working on the Sanitation Worker’s Strike. Where King’s theological journey would have taken him remains a mystery.

While we truthfully, read King (or any other theologian), let’s be sure to read their work self-critically, in context, and with the grace and understanding that we too are on a theological journey, and they too are made in the Image of God.

References

Kirk R. Macgregor, Contemporary Theology: An Introduction, (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2019).

The Danvers Statement, 1998.

John A. D’Elia, A Place at the Table: George Eldon Ladd and the Rehabilitation of Evangelical Scholarship in America, (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2008), 91-183.

Martin Luther, On the Jews and Their Lies, originally published in 1543, republished by Liberty Bell Publications, 2004.

Southern Seminary, Report on Slavery and Racism in the History of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, https://www.sbts.edu/southern-project/, accessed February 21, 2022.

Mark Galli, What to Make of Karl Barth’s Steadfast Adultery, Christianity Today 2017.

Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, Report on Slavery and Racism in the History of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, https://www.sbts.edu/southern-project/, 2018.

Mark Galli, What to Make of Karl Barth’s Steadfast Adultery, Christianity Today 2017.

Clayborne Carson, The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr. (New York: Warner Books), 1998.

Martin Luther King, Jr., Pilgrimage to Nonviolence, The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr. Volume 4: Symbol of the Movement, January 1957-December 1958, ed. Clayborne Carson (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000).

Feb 28, 2022

Feb 28, 2022

Mar 6, 2026