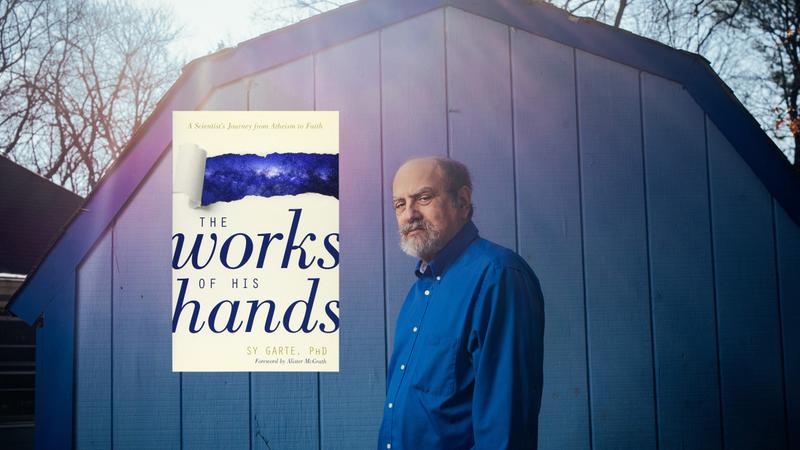

At Peaceful Science, we see value in lucid self-disclosures. It is our pleasure to present this confession from Sy Garte, a biologist, who explains how he came to affirm the Resurrection. Dr. Garte’s story is expanded in The Work of His Hands: A Scientist’s Journey from Atheism to Faith, released today, and this book is significant for our current moment. As an atheist biology professor, Dr. Garte encountered Jesus in a dream.

My parents were dedicated materialistic atheists. I remember thinking as a child that people of faith were lucky because they could fool themselves into believing that there was a loving God. I was well trained in rationalism, and I never thought I would ever accept anything like spirituality or faith.

But as I grew up, I began to feel that I was missing something – a sense of mystery perhaps, or the transcendental. In other words, unlike many others, I never had a religion to lose – I had a vacuum to fill. I read a little about various kinds of mysticism. Then I became a biological scientist and embarked on a career in research, and that seemed to provide the sense of wonder that I felt had been missing in my life.

I began reading about physics, and found that some of the language of cosmology, quantum physics, and relativity didn’t sound that different from the language of mysticism. The more life experiences I gained, and the more science I learned, the more I felt that the reality of our world didn’t quite fit with the purely materialistic paradigm of strong atheism. I became convinced that there might be something….more. I gave up on my certainty that atheism was true and became an agnostic because, at the time, I had no strong reason to believe anything else.

After I rejected the atheism of my upbringing, I spent many years wondering what the truth was about the existence of God. I investigated several theistic and spiritual systems. At one point I became fascinated with Jewish mysticism; I read several books on Buddhism; I listened to friends who had delved deeply into Indian religion; I learned transcendental meditation. (I even peeked into Scientology – and fled.)

All of this convinced me that there really was something that existed beyond the material world studied by science. I called this something “spirituality.” I began thinking that maybe the idea of “God” was the immaterial manifestation of this spiritual reality. But I was also getting the sense that if that was true, God was a very distant and unknowable entity. Both the Kabballah and the sayings of the Buddha seemed to confirm this.

I found myself standing on the shores of a sea of mystery, certain that the waters hid treasures of beauty and goodness, but with no way to see them for myself.

And then, prompted by a friend, I read the Gospels. I had read some of them before in school, but only as an exercise to reinforce my atheistic scorn at the stupidity of Christianity. Back then I was focused on the magic, the contradictions, the naiveté of the ignorant who believed in scientifically impossible events like the resurrection.

When I read the Gospels the second time, my mind was open, freed of the ideological certainty of atheism. I still saw the apparent contradictions, but now they appeared as evidence for truth, the kind of differences one would expect in true eyewitness accounts (1). I still saw what looked like magic, but now it confirmed for me my new-found conviction that science is not the only pathway to truth. And now I saw the figure of Jesus Christ, and reading His words, I realized that God must have seen me standing on the shore, staring helplessly at the waves. Jesus Christ rose from those waters and held out His hand to me.

“So you want to see God?” He asked me. “Here I am.”

The above is a poetic image, but something very similar actually happened to me in a dream. In the dream, I was outside of a walled garden. I knew that in this garden there was to be found everything I had always been looking for, but there was no way I could climb over the wall to get in. I kept going around the walls, trying to climb up, falling down, and getting terribly frustrated. And then a man showed up, and said to me, “What’s wrong with you?” I explained I was trying to get into the Garden but could not scale the wall. He smiled and said, “Then why not use the door?” and pointed to a door in the wall that I hadn’t seen before. I asked what I needed to do to gain entry. He answered, “Nothing, just open the door and go in.” So I did.

I awoke knowing that Jesus Christ was real, He was the incarnation of God, and He was calling me.

Well, let’s take a deep breath. I was at the time of this dream, as I had been long before and remain today, a scientist. I know that dreams are images produced by neurophysiological and psychological impulses, and so, like all subjective experiences, they can be easily explained as materialistic phenomena. Perhaps I had that dream simply because I wanted to. That explanation was the one I had used as a young man to dismiss similar experiences. But now I rejected it, as I had rejected atheism as my worldview.

I thought of the widespread belief among scientists of the late 19th century that there wasn’t much else to learn about the physics of the universe, and the idea that the origin of life would be a simple problem of chemistry to solve. What replaced all these beliefs was not something simpler and more elegant, but theories that are far more complex and perhaps even semi-mystical. To say that dreams are just neurological impulses is like saying a Kandinsky painting is just paint, a Beethoven symphony is just sound waves, and love is just raging hormones. One could as easily say that the ideal gas law or the Schrödinger equation are just letters and symbols with an equal sign in the middle.

Which brings me back to my reading of the Gospels. The figure of Jesus was powerful and produced a sense of awe in my soul. But just as important to me were the other characters in the story. The Acts of the Apostles brought these people into sharp focus. Peter, the man who denied Christ at the end, and Paul, the archenemy of the new faith, sprang off the pages as real people. Peter was weak before he became strong; Paul was headstrong and vicious before he became virtuous.

It was the resurrection of Jesus Christ that produced the transformations of these men. It was that incredible event that called out to so many people of the time. It was the event and led to the growth of a new religion with an estimated million believers within 250 years (2) – despite persecutions, the martyrdom of some of its leaders, (3) and the destruction of Jerusalem.

There was no doubt in my mind as I finished Acts that the resurrection was the central point of Christianity, that it defined who Jesus was and who we are. And I saw myself in Peter, and even more so in Paul. Not because of the great work they did after the resurrection, but because of Peter’s weakness and Paul’s intransigence. And as I finally came to accept Christ as my Lord and Savior (the detailed story is told in my book The Works of His Hands: A Scientist’s Journey from Atheism to Faith, Kregel Publications), I saw that I and all of suffering humanity are perfectly reflected in the transformed lives of these apostles.

But how can a scientist believe in a miracle like the resurrection? I rejected scientism a long time ago, so I had no problem understanding that science has limits, and that miracles, by definition, are not addressable by science.

I have always been enamored of history, and everything I have read about the history of early Christianity confirms my subjective belief in the reality of Christ’s resurrection and divinity. The detailed historical case for the truth of the resurrection has been presented by many, on both academic (4,5) and popular (6,7) levels, and I can only add that I found it convincing from the time I understood the historical reality of the first century.

I believe in the resurrection of Christ because I believe in God, and in Jesus Christ as the incarnation of God on earth, and I believe in the redemption of human beings like Peter, Paul, Mary Magdalene, myself, and you. If there had been no resurrection, there would have been no Christianity, and history would have been entirely different. The moment (a moment described in my book) that I finally realized I was a Christian and dedicated my life to following Jesus, that lifelong sense of emptiness was filled with a brilliant and enlightening new understanding. As C.S. Lewis so famously said,

“I believe in Christianity as I believe that the Sun has risen, not only because I see it but because by it, I see everything else.”

For more information about the book, and to order, please see https://theworksofhishands.com/.

References

J. Warner Wallace, Cold Case Christianity: A Homicide Detective Investigates the Claims of the Gospels David C Cook, Colorado Springs, CO, 2013

Rodney Stark, The Rise of Christianity: How the Obscure, Marginal Jesus Movement Became the Dominant Religious Force in the Western World in a Few Centuries Harper, San Francisco 1997

Sean McDowell, The Fate of the Apostles: Examining the Martyrdom Accounts of the Closest Followers of Jesus Routledge, Abingdon, UK, 2016

Lee Strobel, The Case for Christ: A Journalist’s Personal Investigation of the Evidence for Jesus Zondervan, Grand Rapids MI, 1998

Josh McDowell and Sean McDowell, More Than a Carpenter Tyndale Carol Stream, IL, 2009

N.T. Wright, The Resurrection of the Son of GodFortress Press Minneapolis MN, 2003

Michael Licona, The Resurrection of Jesus A New Historiographical Approach IVP Downers Grove IL, 2010

Links

- https://peacefulscience.org/books/works-hands/

- https://theworksofhishands.com

- https://peacefulscience.org/books/coldcase-christianity/

- https://peacefulscience.org/books/rise-christianity/

- https://peacefulscience.org/books/fate-apostles/

- https://peacefulscience.org/books/case-christ/

- https://peacefulscience.org/books/more-than-carpenter/

- https://peacefulscience.org/books/resurrection-son-god/

- https://peacefulscience.org/books/resurrection-jesus/

Nov 19, 2019

Feb 21, 2022

Feb 24, 2026