Science is not intuitive. From the population genetics of Adam and Eve to Intelligent Design, garden paths lead us to the wrong answer. When you see the garden path for what it is, the error becomes obvious. Others might struggle to see. When asked why I disagree with another scientist, I often respond:

In my honest and professional opinion, their argument just looks to me like 1+1=3, and I just cannot agree. Maybe I am wrong, but that is how it looks to me.

Please do not be offended. I am not saying that their argument is easily determined to be wrong, or obviously false to everyone. Perhaps, also I am wrong. Rather, to me, as a scientist with my training and experience, the argument in question just looks obviously wrong. The more closely I look, the more certain I am that it is wrong. From there, I sometimes explain more. Even if you dive deeper into the conversation with me, it might be hard to see why the argument seems so obviously wrong.

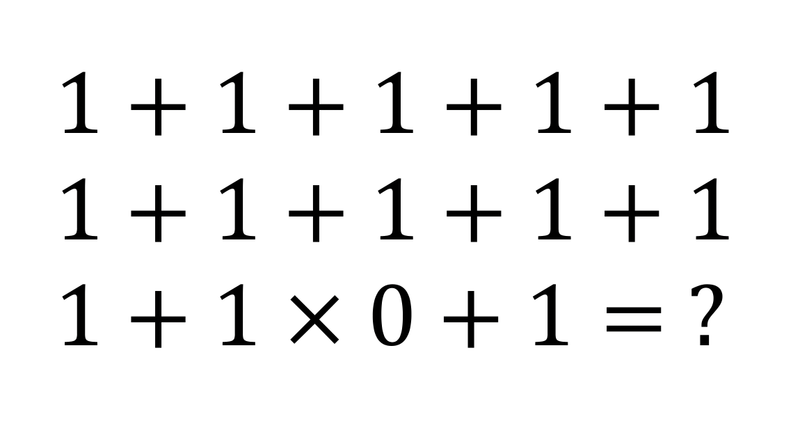

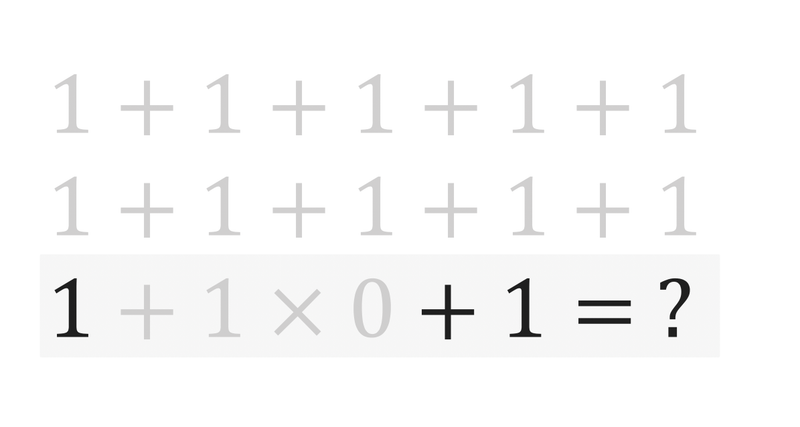

I wonder, however, if this is really the best math problem to use to make my point. Sometimes, perhaps not. This one might illustrate the point more clearly. Try answering this simple math problem before reading further:

What number did you compute? What is the answer? Write it down or otherwise remember it. We will come back to this soon. Simple, right? Turns out that most people get the answer wrong.

Lead Them Down The Garden Path

Changing the topic a bit, let’s talk about sentences instead of math problems. Wikipedia explains that, “A garden-path sentence is a grammatically correct sentence that starts in such a way that a reader’s most likely interpretation will be incorrect; the reader is lured into a parse that turns out to be a dead end or yields a clearly unintended meaning.”

Here are a couple examples from that Wikipedia article:

The old man the boat.

What does that sentence mean? How would you rephrase it?

Turns out that most people parse the sentence wrong because the first few words lead us down the wrong path. We read “old man” first, then struggle with something like “the man (who is old) the boat.” That “old man” misled us! In this sentence, “old” is a noun and “man” is a verb. We could rephrase for better understanding, “The old are the persons who man the boat.”

The complex houses married and single soldiers and their families

This time, we lost our way in the “complex houses.” In this sentence, “complex” is a noun and “houses” is a verb. We could rephrase for better understanding, “The complex provides housing for the soldiers, married or single, as well as their families.”

The person writing the garden-path sentence is not necessarily deceptive. Without intention to deceive, any of us might accidentally write a sentence like this. Rather, it is the sentence itself that is misleading, using our natural intuitions against us. Our brains are so hardwired with these intuitions that these sentences are very difficult to read, even when we are warned upfront that they are garden paths.

The way we misread garden path sentences uncovers important details about how humans understand language, and how we reason about the world. For this reason, garden path sentences are an active area of research. We use heuristics and intuitions to parse even the most simple sentences. These intuitions are usually correct, but they fail on sentences that lead us down a garden path.

The Math Problem’s Garden Path

Let’s return to the math problem. What number did you compute? Most of us computed an answer of 12, but that is wrong. Commonly, we first multiply the 1×0 to get a zero, and then add up the rest of the 1s to get 12. Maybe you miscounted and arrived at a different number, but the road to 12 is the most common path taken, the garden path.

The correct number is actually just 2, not 12. Can you see why? Soon it will be obvious, but perhaps it is not obvious yet.

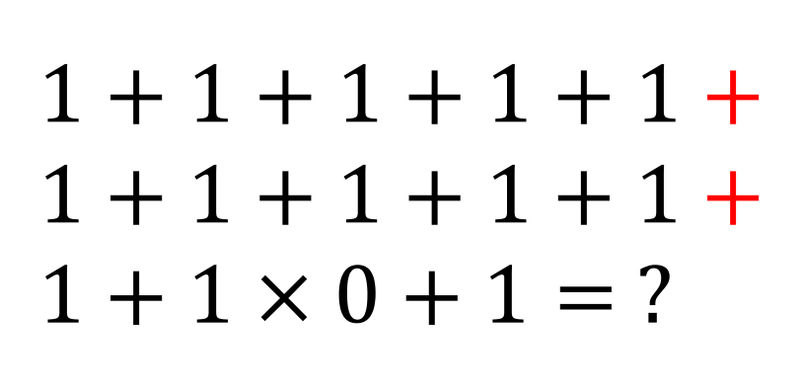

The first two lines of the image are not part of the equation. The equation is only the last line. Several factors collaborate together to create a garden path.

- The first two lines are first and they fill most the image, so the just must be relevant to the problem, but they aren’t…

- The first two lines are symmetric and repetitive, so we just glance at them without checking if those lines terminate in “+” signs, and they don’t…

- The irregularity of “x 0” catches our attention, the ends of lines are neglected…

- That 1×0 has us multiply first, before counting up all the 1s, but 10 of those 1s are on the garden path…

All these features together lead us to misread the problem, taking us down the garden path. Then, in place of the problem we were presented, we answer this problem instead:

Clear away the distracting clutter of the problem. All that is left is “1+1×0+1=?” or “1+1=?,” and we all know that 1+1=2. Once we see the garden path for the wrong turn that it is, we just cannot agree that the answer is 12. We might even get frustrated when another scientist insists the answer must be 12. We repeatedly checked that there really are no plus signs at the end of the line! So, it really looks like they are claiming 1+1=3, or in this case, 1+1=12.

The Garden Paths of Science

I see this over and over again in science. Take this example from The Genealogical Adam and Eve (p. 104), where I caution against stating:

It seems the human population was never just a single couple.

Turns out that this claim might be true, but science cannot tell us for sure. Many scientists stated it as fact because it seems our ancestors (not the same thing as human) never dip down to a single couple. We cannot take the meaning of human for granted. For many definitions of “human” (e.g. Homo sapiens), our ancestors at times include more than just humans alone, so the human population can be smaller than the population of our ancestors as a whole. Go back in time far enough, at some point there will be zero humans, so what evidence is there against a human population of two?

For this reason, if a scientist claims that “science demonstrates that the human population was never just a single couple,” confidently citing evidence of large ancestral population size…well, this just looks to me like 1+1=12. I understand how he arrived at the wrong answer, and this is why I just cannot agree. They arrived at their answer after walking down the garden path, and perhaps they even took others along with them.

The same sort of issue comes up with Intelligent Design. Take a look at their “ Scientific Dissent from Darwinism,”

We are skeptical of claims for the ability of random mutation and natural selection to account for the complexity of life. Careful examination of the evidence for Darwinian theory should be encouraged.

Well, current understanding of evolutionary science shows that “Darwinism,” which is defined here as “random mutation and natural selection,” cannot account for the complexity of life. Other mechanisms are important too. It matters too, because we have to take into account the full complexity of current thinking to make argument against evolutionary mechanisms. In a debate with Behe a couple weeks ago, I explained this in part.

The Dissent might as well be a “Scientific Dissent From Newtonian Mechanics,” somehow forgetting that physicists know the law of gravity is just an approximation, and for almost a century have been teaching that relativity works better. I have not even touched on the fact that science does not even purport to give a complete account any ways, so even then we will not be able to fully account for much of anything.

So The Dissent just looks like 1+1=8 to me, obviously out of step with current understanding in science. Sometimes, I admit, this sets the conditions for frustrating interactions. From a podcast last week, here is how William Lane Craig describes a conversation he observed when we first met:

I met him first at the Dabar Conference at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School which is a conference of the so-called Creation Project investigating these origins questions. He was there. He’s [computational] biologist from Washington University in St. Louis. He made quite an impression on me because during one of the sessions the speaker was talking about Darwinism, and Swamidass stood up from the floor (and he’s a big fellow) and he says to this fellow, Why do you keep talking about Darwinism? Darwinism has been dead for over a hundred years. And the fellow says, Well, alright then, neo-Darwinism. And Swamidass wouldn’t let go. He said, Neo-Darwinism has been dead since the late 1960s. Why do you keep attacking these obsolete views rather than the views that are current in evolutionary biology?

That was an ID scientist. He was not a biologist though, so perhaps he was just taking everyone else’s word about Darwinism. I am not at all intending to imply he was being deceptive, or was not a smart guy. Still, what he was saying just really looked like 1+1=5, at least to me with my training and experience.

I could list other examples like this from every camp in the conversation: YEC, OEC, ID, and EC. I am not immune of course. I am sure a scientist that looked closely could find places I make similar mistakes of my own. When they are brought to my attention, I hope I am quick to correct these sorts of errors.

Here is the thing. Science is not intuitive. It is technical, mathematical, and complex. As we learn the details, our intuition is reworked. Our intuitions are refined and reshaped as they are exposed to data and other experts. As our intuition is reworked, we learn to tune out the distractions and irrelevant information.

In the end, our intuitions work differently, more rigorously. Now we have a chance of avoiding the garden path. The most subtle scientific errors might even become obvious. We might even have to relearn that what is readily apparent to us is not obvious to others.

So, that is what I mean by “it looks like 1+1=3.” Though, with the math problem of this post in mind, perhaps I should start saying “it looks like 1+1=12” instead? Whatever I end up doing on that particular question, we should all remember one critical point…

Whatever you might have heard from others, 1+1=2.

References

- https://peacefulscience.org/articles/three-stories-on-adam/

- https://peacefulscience.org/articles/agree-behe/

- https://peacefulscience.org/articles/fair-hearing-behe/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Garden-path_sentence

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sentence_(linguistics)

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parsing

- https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C26&q=garden+path+sentences&btnG=&oq=garden+path+

- https://peacefulscience.org/books/genealogical-adam-eve/

- https://discourse.peacefulscience.org/t/_/61/4

- https://peacefulscience.org/books/adam-genome/

- https://peacefulscience.org/articles/defense-tim-keller/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Scientific_Dissent_from_Darwinism

- https://discourse.peacefulscience.org/t/_/9745/21

- https://discourse.peacefulscience.org/t/_/6788

- https://www.reasonablefaith.org/media/reasonable-faith-podcast/josh-swamidass-on-adam-and-eve-part-1

Mar 6, 2020

Dec 5, 2021

Jan 25, 2026