If C.S. Lewis right, and imagination really is the organ of meaning, fiction is a powerful way of explore the world. The Genealogical Adam and Eve imagines one way of understanding Genesis, but there are others. We interviewed, Brian Godawa who, in his series of novels, also joins the ancient midrash tradition of fictional retellings of Genesis. He is an award-winning Hollywood screenwriter, a provocative movie and culture blogger, an internationally known teacher on faith, worldviews and storytelling, and an Amazon best-selling author of Biblical fiction, and imaginative theology.

What draws readers to your work?

You have written several interesting novels, including several retellings of Genesis. Can you name and explain the “genre” of your work, and tell us what you think draws readers to your work?

I write supernatural epics based on Bible stories. But I like to call them theological novels because even though I seek to be consistent with the Bible, I use fantasy as a genre to depict the spiritual world. While Scripture uses a lot of poetic imagery to provide hints, it is not always clear or meant to be literal.

The Bible does this for instance with its imagery of the sea dragon, Leviathan. A study of Leviathan reveals that it is not a literal creature in the natural world, but rather a symbolic image of chaos that all ancient Near Eastern peoples at the time were familiar with and used in their own literature ( see my article on Leviathan here). It represents the chaos that Yahweh pushed back to establish His covenantal order. The historical crossing of the “Red Sea” (Yam Suph) was described in Psalm 74 utilizing Leviathan as the symbolic theological expression of what Yahweh was doing historically in rescuing his people for covenant. Leviathan appears throughout my book series as a fantastical embodiment of this chaos that exists in the spiritual realm.

The authors of the Bible were quite sophisticated in their use of symbolic imagery to communicate theological truths. They retold historical events and made miraculous claims. It is a both/and, not an either/or proposition. History and theology is intermixed. I do the same with my novels.

The main storyline that all my book series tell is Christ’s victory over the spiritual powers, or Christus Victor. Evil spiritual forces are authorities over the Gentile nations and they seek to destroy the bloodline of the Messiah because it is He who will come to disinherit those powers, to “take back the nations” into the Kingdom of God. Is it just theological or is it literal? Could it be both? Christians have varying degrees of how they interpret that. The narrative is definitely in the Bible. I just want to retell that storyline that has been overlooked by our modern western worldview of understanding in a creative and relevant way – maybe that’s what draws readers to my work.

What can we learn from the midrash tradition?

Many old texts are examples of “ midrash,” an ancient Jewish literary tradition of creative retellings and extrapolations of stories in Scripture. Your writings might be a continuation of that midrash tradition. What purpose did creative extrapolations serve for ancient storytellers? What could they add or provide that the stories themselves could not alone? What can we learn from this tradition?

My novels are deliberate Midrash in that Jewish tradition. They aim to retell Bible stories with theological insights for modern times. The problem as I see it is that the “modern” western view of reading the Bible “in plain language” or “literally,” is actually a form of cultural imperialism. We are so far removed in terms of language, culture and time from that of the Bible that to read it in English, in our own “plain” language is to often misread the Bible. We should seek to understand it within the ancient Near Eastern context in which it was written and originally understood. Placing ourselves in the shoes of an ancient Jewish reader, we may discover new meaning in scripture very different from our own.

For example, when we read prophecy texts that talk about the universe collapsing and stars falling from the sky, the modern reader may assume this to be literal. But in the ancient world, it was clearly symbolic imagery about the fall of earthly and spiritual powers. What is “plain language” to the ancient Near Eastern mind is not necessary “plain language” to our modern western mind.

The Bible incorporates a lot more symbolism and imagination in its theology than the modern mindset of Christians may want to allow. And we must respect the original context in order to understand what God said to them, and may be saying to us through them.

I have found that the more I seek to understand the Bible in its original ancient context, the more I find that I have missed with my modern bias. There is an entire movement of scholars exploring this understanding, including theologians like Michael S. Heiser, John Walton, N.T. Wright and others.

What draws in secular readers?

Are any of your readers secular, who do not personally believe the Bible is true? What do you think draws them in?

My dominant audience is Christian, but I have had others outside of the Christian tradition who are interested in the supernatural or the paranormal appreciate my stories. There are many who believe the Bible is mythological, but still embodies the truth about human nature and God. They see the power of story to capture that truth. And they can appreciate my stories.

Like C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, I think the Bible is both historical and mythical. It is “ myth become fact,” as Lewis put it. So I have no problem wrestling with the deeper truths of myth in my stories. I even incorporate pagan mythology into my stories, not in a syncretistic way, but in a subversive way, submitting all myth to the Lordship of Aslan, as Lewis would put it.

Does screenwriting shape your storytelling?

You are a screenwriter too. How does your experience as a screenwriter shape your approach to writing and inform your storytelling?

I want to write stories that read like a movie. I like fast-paced drama that is to the point and concise. Many have told me that is how they read my stories.

My Hollywood storytelling has helped me to have a strong sense of story structure that I think lacks in some novel writing. Some novelists think that the details or words are more interesting than the story itself so they focus on the language, on being a “word-smith.” For me, that’s like losing the forest for the trees. I am a forest guy. Yes, I love saying things with words, but they must serve the story well, because the story is paramount. I think if the reader doesn’t wonder “what is going to happen next?” then you’ve lost their interest.

The power of Hollywood screenwriting is that you have to learn how to say more with fewer words, to be more economical. You have to know how to communicate through showing your audience, not always telling them. A person’s actions and choices show who they are. Readers like to figure things out. They don’t always want to be told what to think. For me, actions speak louder than words when it comes to character development and storyline.

Give us a guide to your novels?

For those who are new to your work, can you give us a “guide” to your novels, especially those relevant to origins?

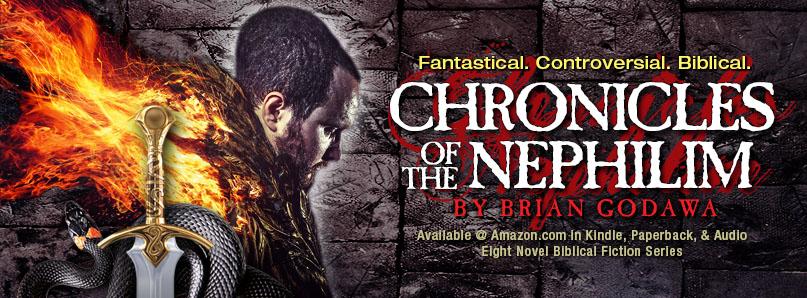

Chronicles of the Nephilim: A saga that charts the rise and fall of the Nephilim giants of Genesis 6 and their place in the evil plans of the fallen angelic Sons of God called “The Watchers.” The story starts in the days of Enoch and continues on through the Bible until the arrival of the Messiah, Jesus.

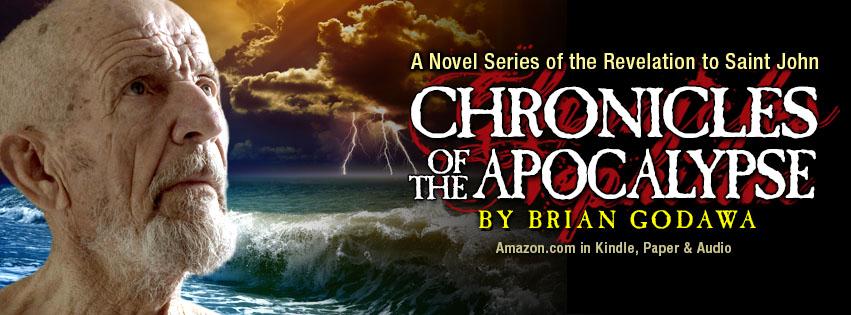

Chronicles of the Apocalypse: An origin story of the most controversial book of the Bible: Revelation. A historical conspiracy thriller trilogy in first century Rome set against the backdrop of explosive spiritual warfare by Satan and his demonic Watchers. The Sequel to Chronicles of the Nephilim.

Chronicles of the Watchers: A series that charts the influence of spiritual principalities and powers over the course of human history. The kingdoms of man in service to the gods of the nations at war. Completely based on ancient historical and mythological research.

Talking Points for the series:

Answers many Biblical oddities that have stumped people for years, such as the true meaning of Leviathan and Behemoth, the explanation of the Tower of Babel, the reason for giants in the Bible, the identity and purpose of the angelic Watchers in the Bible, strange mythical creatures in the Bible like Lilith, Azazel, satyrs, and winged fiery serpents, why Sodom and Gomorrah really was destroyed, the moral difficulty of the Holy Wars of Yahweh in the book of Joshua, the reason for Satan arguing over Moses’ body, the ancient book of Enoch, and much more.

Explains the spiritual origins of many ancient mythologies.

A Biblical epic that uses the fantasy genre to express theological truth. Just like Lewis and Tolkien did.

Maintains high respect for the Biblical text, while filling in gaps with imagination based on Biblical images and metaphors.

Appendices in every book provide the interesting Biblical and ancient Near Eastern research behind the imagination in the novel. Scholarly and imaginative.

Gustave Doré (1866).

How do you balance creative license and faithfulness to Scripture?

In your book series Chronicles of the Nephilim, you retell stories in the Bible that have giants in them, perhaps the most familiar of biblical giants being Goliath which you talk about in book seven of this series, David Ascendent. How do you balance the creative license and imagination required for fantasy while remaining faithful to scripture in your retellings of biblical stories?

I have a few rules. First, it is not to contradict anything in the Bible that is theologically meaningful. I may use hyperbole to benefit or enhance the story, but not to change it. So, for instance, I am convinced that the Bible says there were giants in the land of Canaan, but that word to a modern reader means something different than to it would’ve to an ancient audience.

When we think of giants, we think of 20 feet or taller monsters. But the word in Hebrew simply means tall people. The only sizes of “giants” that are specified in the Bible are that of Goliath ( 9 1/2 feet tall – 1 Sam 17:4), Og of Bashan (his bed of 13 1/2 feet – Deut 3:11) and an unnamed Egyptian giant “of great stature, seven and a half feet tall” (1 Chron. 11:23). One ancient Egyptian papyrus describes bedouin nomads in Canaan (possibly the Anakim of the Bible) as being 7 to 9 feet “from their nose to their foot and have fierce faces.” (Wente & Meltzer, 1990) A reference in the Apocryphal book of Jubilees 29:9 says, the giants of Canaan had heights from 10 1/2 feet to 15 feet tall. Jewish historian Josephus writes of a giant in his day being 10 1/2 feet tall. Roman historian Pliny wrote of a giant in the first century named Gabbaras who was over 9 feet tall (So I put him in my series Chronicles of the Apocalypse). There may have been some hyperbole, but giants were not merely a mythical construct in the ancient world.

Now, there is a strong biblical scholarly argument that the original text about Goliath puts him at about 6 feet 6 inches. And the bed of Og is most likely a reference to his grand royal sarcophagus, not his bed. The average height of ancient Israelites was about 5 foot 6 inches. So, in truth, a 6 1/2 foot tall warrior would be considered a “giant.” Realistically, these clans of tall people were probably more like modern day basketball players with an average height of seven feet. I wanted to be within the realm of the ancient texts to be consistent with them. But in order to make the action more exciting and to make the stakes more exciting, I went ahead and made my Canaanite giants lean toward the taller heights of nine feet and even eleven feet tall. I made one anomalous giant over fifteen feet tall. But a few feet of hyperbole doesn’t change the meaning of the text.

And that brings me to my second rule. I put appendices in all my novels to explain my research so people can see where I got my information and where I took creative license.

Thirdly, I use fiction to fill in the gaps between stories or events in the Bible, but I aim to do so in such a way that they will fit coherently within the context of the rest of the Bible without contradicting it. So the fiction is still possible.

Fourthly, the more ancient the story, the more fantasy elements and hyperbole I use because I believe that the “primeval history” of ancient texts such as Genesis 1-11 is not history the way we write it, but more of a theological history the way ancient Jews wrote it (midrash tradition). So I mimicked that.

Fifthly, any fantastical element that I used, like satyrs, or Leviathan or even vampires, were always based on actual ancient legends and were used more for their theological meaning than their hyperliteral existence. I was not very original with any of my creative license. I wanted to use material from ancient literature to bring the reader into the ancient mindset. This is akin to the Biblical writer Isaiah describing satyrs dancing on the graves of Edom and Babylon (Isaiah 34:11-15; 13:21-22). They used the pagan gods and “demonized” them to mock their enemies. By literalizing them in my story, I made the demonic reality more tangible, but kept the same meaning.

What have you learned through retelling old stories?

In the Preface to Noah Primeval, the first book in your Chronicles of the Nephilim series, you write: “In short, I am not writing scripture. I am not even saying this is how the story might have happened…I am retelling a biblical story in a new way to underscore the theological truths within it.” How do you even begin to retell stories so ancient and familiar as those found in the Bible, in a new way? Has your retelling and reengagement of biblical stories uncovered new theological truths for you?

This entire journey of retelling Bible stories began when I discovered Michael S. Heiser’s book The Unseen Realm and realized that a strong Evangelical argument could be made from the Bible for the Christus Victor storyline, as well as a supernatural view that I had not seen before. That there was more imagination at play in the text than I wanted to admit.

How does modern science fit into the narrative?

As a Christian who has written supernatural epics on biblical stories, including the creation account in Genesis, what are your thoughts on how modern science fits into this narrative as well? How do you put everything together?

I was a young earth creationist for most of my Christian life. It seemed so clear to me that the meaning of Genesis was hyperliteral. For me at the time, it was describing the physics of creation like a science textbook, and so the creation narrative was not compatible with Evolution. I believed in scientific concordism, that the Bible must be in accordance with modern science. For me the Bible held together best with young earth creationism, thus I espoused that view. However, if evolution was right, I felt as though so much was at stake for the Bible and me. That would mean the Bible was all wrong, and I would have to reject my faith. I’ll admit that seeing things this way was frightening to me. But I have always been interested in seeking truth, no matter where it leads. So I faced my fears head on.

Reading works from scholars like John Walton, Darrel Falk, Dennis Lamoureux and others, opened my eyes to the nature of ancient creation stories, such as that in the Bible. Studying the biblical text alone, I realized that the Bible is not a science textbook, and that in fact the purpose of ancient creation stories was nothing like our modern creation story of physics and material.

But then after much study I realized: Who says that the Bible has to concord with modern science? That is a modern prejudice. The Bible does not say that anywhere. It does not claim to depict the physics of the universe, it claims to explain the theological meaning of creation.

God was not intending on communicating science to us. He was using ancient men with whatever cosmological view they had to communicate spiritual truth, not science. The belief that the Bible has to be scientifically or even historically precise by our standards of precision is cultural imperialism, imposing our perception upon God’s Word. How dare we?

Ancient creation stories are about establishing the superiority of one’s deity and its ownership of land and people.. Creation is a description of God’s covenant with his people, even in polemical opposition to Egypt, Canaan and the Gentile nations. It is not a story about the origin of material, but the function or purpose of God’s creation.

It was at that point that I was no longer afraid of evolution in general. If it is right, it does not contradict Genesis at all, because Genesis is not a science book about physics, it is a theological book about meaning. Of course, there is much more to it than that, but my point is that I then became willing to consider evolution without fear of losing my faith. While I still do not believe in macro-evolution for empirical, scientific, rational and moral reasons, it is no longer for biblical hermeneutical reasons. God’s Word simply does not speak to science or evolution with doctrinal intent. In the end, if evolution is true, it wouldn’t hurt my faith. I am not as closed off to it like I used to be.

References

Edward Frank Wente and Edmund S. Meltzer, vol. 1, Letters from Ancient Egypt, Writings from the Ancient World, 108 (Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1990).

Links

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Adolf_Behrman_-_Talmudysci.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Goliath#/media/File:071A.David_Slays_Goliath.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gustave_Dor%C3%A9

- https://peacefulscience.org/books/genealogical-adam-eve/

- http://godawa.com/movies/feature-films

- http://www.godawa.com

- http://godawa.com/public-speaking/home/http://godawa.com/public-speaking/home

- http://godawa.com/chronicles-of-the-nephilim

- http://godawa.com/books/god-against-the-gods

- https://www.academia.edu/4617559/Leviathan_Sea_Dragon_of_Chaos

- https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Psalm+74&version=NIV

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Midrash

- http://judithwolfe.wp.st-andrews.ac.uk/files/2017/08/Myth-Became-Fact.pdf

- https://amazon.com/dp/B012A5CALO/

- https://amazon.com/dp/B07KRFP1BV/

- https://amazon.com/dp/B07ZZ7RCYH/

- https://godawa.com/chronicles-of-the-nephilim

- https://peacefulscience.org/books/david-ascendant/

- https://peacefulscience.org/books/unseen-realm/

- https://pixabay.com/users/KELLEPICS-4893063/

- https://pixabay.com/

May 5, 2020

Oct 19, 2021

May 19, 2025