Greg Cootsona (PhD, Graduate Theological Union) is the author of Mere Science and Christian Faith, Bridging the Divide with Emerging Adults, a book that unintentionally sparked a conversation about the place of Intelligent Design (ID) in the Church and in science. Looking beyond this controversy, I highly recommend this book for its accessible review of a wide range of key topics, along with practical wisdom for pastors, parents and students alike. Director of Science for the Church, Cootsona is both professor and a pastor, informed and deeply invested in the Church.

This book only addresses ID in one brief chapter, reproduced below, but it stimulated vigorous response from the Discovery Institute and World Magazine, to which Cootsona replied on his blog. The chapter on ID, though short and not the focus of the book, is worth looking at more closely. Some of our readers may disagree with Cootsona on some of his focused points, but he is an informed scholar who cares deeply about the Church. His analysis of Intelligent Design deserves a careful consideration by everyone.

I wonder at the hardihood with which such persons undertake to talk about God. In a treatise addressed to infidels they begin with a chapter proving the existence of God from the works of Nature….This only gives their readers grounds for thinking that the proofs of religion are very weak…. It is a remarkable fact that no canonical writer has ever used Nature to prove God.

– Pascal

At this point, I need to address those in the church who are convinced that mainstream science has gone in the wrong direction. If so, as the argument goes, there’s no theological conflict with “real science.” It’s just that science is based on its own faith, namely materialism or naturalism. For those who have questions about evolution, are there viable competitors?

Intelligent Design, or ID, presents an alternative to young-earth creationism for those who resist the idea of evolution through natural selection. This movement has some heavy hitters in its ranks, among them Cambridge-trained philosopher of science Stephen Meyer, university biologist Michael Behe, and, perhaps most surprising, prominent UC Berkeley constitutional law professor Phillip Johnson. So it cannot be immediately written off as a farce proffered by thoughtless creationists. Allow me then to offer an overview of its principal assertions and its history, as well as an evaluation by other scientists.

Three interlocking core convictions summarize ID, but certainly do not exhaust it as an intellectual project:

- Neo-Darwinism is inherently atheistic and materialistic.

- The intricate design of creation points to an intelligent designer (thus the movement’s name).

- Evolution cannot be sustained on scientific grounds because of its inability to address key elements in nature, such as presence of information in DNA and irreducible complexity.

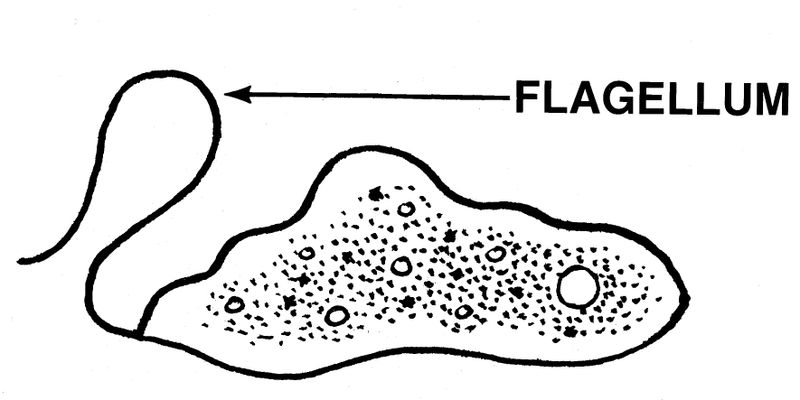

To trace the major plot points in the history of ID, let’s head back to 1991 and the publication of Phillip Johnson’s groundbreaking book, Darwin on Trial. In this work Johnson analyzes the case for Darwinism— and I emphasize the term “case” since his specialization is law—and seeks to raise plausible reasons that we should not subscribe to it. The case is not persuasive, as it were, “beyond a reasonable doubt.” As a result of this work, he and others put forth the idea of “teaching the controversy,” or promoting the problems of Darwinism. (Whether this particular controversy exists remains its own controversy.) Five years later, Lehigh University’s Michael Behe released Darwin’s Black Box: The Biochemical Challenge to Evolution, which presented his concept of irreducible complexity. He claimed that because several biochemical systems—the bacterial flagellum, for example—are too complex to evolve gradually through natural selection, they must be the result of intelligent design instead of evolutionary forces. All this (and more) became bound together in a well-financed conservative nonprofit Discovery Institute, a public policy think tank in Seattle.

A period of growth and optimism for ID lasted at least a decade. Though its proponents didn’t have much success with professional scientific journals, they achieved some popular support. As part of their strategy—and partly due to rejection by professional scientists—they promoted their own textbook, Of Pandas and People: The Central Question of Biological Origins. But these initial forays ran into a wall with the “Dover case” in 2005, or, more accurately, Tammy Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District. In October 2004, the Dover Area School District in Pennsylvania altered its biology curriculum to teach Intelligent Design as an alternative to evolution, with Of Pandas and People to be used as a reference book. When this decision was challenged in court, presiding judge John E. Jones III adjudicated that ID was essentially religious and not scientific in nature; thus the paradigm could not be promoted in public school curriculum. This case is sometimes referred to as “Scopes Two” in reference to the 1925 court case over the teaching of evolution in Tennessee (often called the “Scopes Monkey Trial”).

I have repeatedly asked Christians who are scientists (and thus have no commitment to atheism, nor to denying that God is an intelligent designer in the more general sense) what they think of Intelligent Design. They roundly tell me, “Greg, it just doesn’t add up, and evolutionary science has been repeatedly validated.” One academic colleague in the sciences told me that ID (and seeing atheist scientists as enemies) is a “poison pill” because the paradigm has been so discredited scientifically.

Nevertheless many Christians continue to subscribe to ID, and one reason is that Intelligent Design brilliantly wins the naming game. In a certain sense every Christian is an IDer—we all believe that God is an intelligent designer and that “the heavens declare the glory of God” (Psalm 19:1). We also know that “since the creation of the world God’s invisible qualities—his eternal power and divine nature—have been clearly seen” (Romans 1:20). And for many Christians, ID offers a grand narrative that’s scientific but not coldly materialistic, like Richard Dawkins’s “blind, pitiless indifference.” It asserts a specific mechanism that is detectable and through which a certain handiwork can be proven.

Theologically, though, ID runs into significant problems. For one, we don’t have to believe that God’s creation is detectable through irreducible complexity. The problems are whether “design” can be detected and proven scientifically, specifically through examples of complexity, and whether God’s creation has to be entirely supernatural. That generally is the category for something unusual, a “miracle,” “sign,” or “wonder.” But recall dual causation from chapter one—God as first cause works through secondary, intermediate, and natural causes. When God works, he can certainly use natural means. When he “knit [us] together in [our] mother’s womb” (Psalm 139:13), God acts through the processes of gestation, not supernaturally. And this hits the Achilles heel of ID. There’s a part of me that thinks that if only ID grasped dual causation, the whole paradigm would delightfully unravel.

What kind of creator has to insert himself only at moments of irreducible complexity? It reduces our Lord to a “God of the gaps” who can be detected only when his finger (as it were) touches the places where our human knowledge is faulty. But like so many gaps in the past, this strategy is doomed when science fills in those putative “gaps” with natural causes. It isn’t that much easier philosophically.

My friend and colleague, the philosopher Ric Machuga, offered me a few reasons for ID’s philosophical failures, which I paraphrase here. The Intelligent Design argument, at its root, is an attempt to deduce “design” (and hence, a “designer”) by calculating something’s mathematical complexity. But design and complexity are not the same thing. A mathematical equation specifying the precise location of each and every atom in Mt. Everest would be extremely complex, but that is hardly a reason to believe that Mt. Everest was “designed.” On the other hand, there are only two moving parts in a pair of pliers, yet pliers are certainly designed. So too in nature—we are designed in a sense for empathy, morality, and relationships. A statement about design cannot be tied with mathematical complexity or statistical improbability.

All in all, if I had written this book a decade ago, I would have had to spend more time on ID. Even the philosopher and theologian of science Philip Clayton, when writing his introduction to religion and science for Routledge in 2012, felt compelled to address ID and standard evolutionary theory, but that strikes me as the burst before the setting of ID’s sun. Today, if you search for news about Intelligent Design as a theory, you’ll find most is created by the Discovery Institute.

- To wrap up, here’s a summary of key points and action steps we can take regarding Intelligent Design: Remember that though all Christians believe that God is an intelligent designer, not all subscribe to the particular paradigm of Intelligent Design. This is a critical distinction.

- ID has not been sustained scientifically. So be careful of promoting it. As mere Christians engaging with science, let’s be sure the scientific findings we promote are legitimate. Here conversation with scientists we know can keep us from a multitude of intellectual sins. At the same time, it’s always worthwhile to engage those thinkers who are convinced by ID and find out their reasons why.

- We need to be careful of seeking more from the book of nature than it offers. As far as various sciences can tell us, there is no empirically detectable proof for God’s creation or existence. We may join nature “in manifold witness” (to quote the hymn), but that means neither nature generally nor human beings specifically are a proof for God. We are simply witnesses.

I have worked with questions that are properly in the realm of science. Now it’s time to turn to technology and to call out all the good there we can find. (And there’s quite a bit.)

Note: Hyperlinks are not in the original version. As is reflected in the most recent printings of the book, the spelling of Meyer’s name was corrected, as was the incorrect reference to his “Oxford,” rather than “Cambridge,” training. A typo was corrected too, replacing “principal” with “principle.” We thank Stephen Matheson for identifying these errors.

References

- https://peacefulscience.org/books/mere-science-faith/

- https://www.csuchico.edu/corh/people/faculty/gregory-cootsona.shtml

- https://peacefulscience.org/articles/garden-path/

- https://scienceforthechurch.org

- https://evolutionnews.org/2018/04/intervarsity-press-stumbles-with-sloppy-anti-id-book-by-biologos-advisor-greg-cootsona

- https://world.wng.org/2018/05/mere_distortion

- https://evolutionnews.org/2018/06/mere-manipulation-using-c-s-lewis-to-pitch-evolution-to-christians

- http://cootsona.blogspot.com/2018/04/the-state-of-conversation.html

- https://peacefulscience.org/articles/tour-pascal/

- https://peacefulscience.org/articles/agree-behe/

- https://discourse.peacefulscience.org/t/_/8409

- https://peacefulscience.org/books/darwin-trial/

- https://peacefulscience.org/books/darwins-black-box/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Of_Pandas_and_People

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kitzmiller_v._Dover_Area_School_District

- https://peacefulscience.org/books/religion-science/

Sep 28, 2020

Dec 22, 2021

Mar 6, 2026