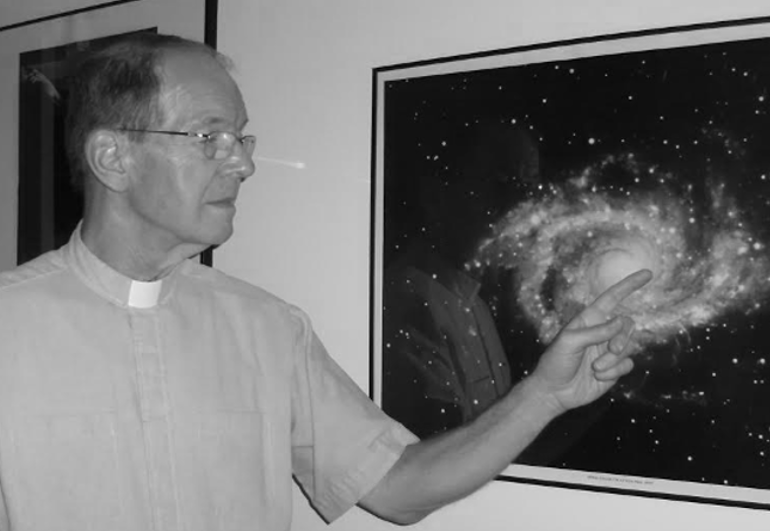

I am very pleased to include this answer from Dr. George Murphy, Ph.D. in Physics and theologian. Answering the riddle of the 100-year old tree, he notes God is not deceitful, but He is subtle: in both nature and the cross. He is a Templeton Prize winner, and one of my theological influences. In particular his work explaining the difficulty with the Two Books analogy and the theology of the cross is particularly insightful. He offers a “theology of nature” in place of “natural theology,” and this has become my aim too.

In the parable of the 100-year old tree we must consider the views of the scientist and the theologian. The scientific argument for an age of 100 years is straightforward.

The science of dendrochronology enables us to estimate a tree’s age from its number of growth rings. This is not as simple as “one ring = one year” because weather conditions play a role, and a given tree must be compared with others in the same environment. But even though some variation is possible, an age of one week for a tree with 100 rings is far outside anyone’s experience. The age is therefore approximately (N.B.) 100 years.

That argument assumes the regularity of nature – that natural processes obey rational laws. Scientists, religious or not, believe in an orderly universe.

The theologian needn’t make a detailed argument because, by the parable’s opening hypothesis, God created the tree a week ago. In addition, the scientist’s appeal to the regularity of nature can be challenged. That is just Hume’s faulty argument against miracles.1 The fallacy is that whether or not nature is indeed completely regular is precisely what’s at issue here.

But why would God create a tree with a deceptive appearance of age? The theologian has no good answer. To test our faith? Faith in what? We can’t explore this further within the limits of the parable since we’re not told how we’re supposed to know what God did or what God we’re talking about. Is it the “Supreme Being” of philosophical theism, the God of the Bible, or something else?

So I will go beyond the parable and talk about the real world. The God I speak of is the Holy Trinity, who is most fully revealed in the life, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. And the tree that we will consider is the cross of Christ, from the standpoint of which we view the universe.

To say that God is most fully revealed in Jesus means that in the Christ event we see what kind of God the true God is and God’s typical modus operandi. As Gordon Fee says in commenting on Philippians (2:5-11), “In’pouring himself out’ and ‘humbling himself to death on the cross’ Christ Jesus has revealed the character of God himself.”2

The “kenosis” or “emptying” of Philippians 2:7 means that in the Incarnation, the Son of God did not simply dress up like a human but limited himself to the condition of a male Jew brought up in the culture of first century Palestine.

This divine self-limitation is important for understanding not only the saving work of Christ but the way God acts in the world.3

That God does act in the world is a statement of faith, not science. We know, for example, that our food comes through natural processes and human activity. We do not “see” God at work. But Jesus’ instruction to pray for daily bread implies that God is indeed at work in all of that.

To understand the relationship between God’s activity and the actions of creatures, we can begin with the traditional idea that God cooperates with creatures in their actions. Things in the world are, metaphorically, “tools” with which God works. The fact that natural processes can be described by rational laws then suggests that God limits such work to conform to basic laws he has created, exercising ordained rather than absolute power. That self-limitation is another expression of the divine kenosis exemplified by Christ, the sign of the cross placed on creation.

This enables us to understand theologically why divine action cannot be inferred from scientific investigations. This does not simply have to be accepted as brute fact. God is hidden in his work in the world, just as God is hidden to ordinary observation and thought in the God-forsakenness of Calvary. God’s tools are also, in Luther’s phrase, the “masks” of God. “Truly, you are a God who hides himself, O God of Israel, the Savior” (Isaiah 45:15).

By working in this way God makes creatures genuine participants in the project of creation. They are not just inert objects to be moved around like pieces on a chessboard. And apparently God wants humans (and perhaps other intelligent creatures) to be able to understand the creation with the powers of observation and reason God gives us instead of being like lazy students looking up the answers in the back of the textbook.

Belief in the resurrection of Jesus means that we must not insist that God cannot bring about events contrary to the ordinary course of nature. Hume was wrong – but he had a point. We would be skeptical about claims that some otherwise undistinguished person was raised from the dead. The significance of Jesus as part of the whole history of Israel, the gospel accounts of his life and the subsequent development of the Christian community force us to take the possibility of his resurrection seriously, not simply as an arbitrary oddity but as “the first instantiation of a new law of nature.”4

In conclusion, we consider a real world parallel to our parable. Defenders of a literal interpretation of Genesis 1-3 sometimes appeal to the idea of “apparent age”, the possibility that God could have created the world a few thousand years ago but made all of its features – appear to be billions of years old.5

There is no logical or scientific way to refute this idea,6 but it is widely rejected. It would make God a deceiver and the whole creation a giant lie. Suggestions that a cosmic fall consequent upon human sin changed the universe so radically that our scientific determinations of its age are all invalid are tantamount to the old Manichaean heresy that evil has genuine creative power.

God does not deceive us, and has created a universe that will reveal the truth about itself to those who study it carefully and honestly. As Einstein said, “The Lord is subtle but he is not malicious.”

References

- http://www.asa3.org/ASA/PSCF/2006/PSCF3-06Murphy.pdf

- http://biologos.org/blogs/archive/surveying-george-murphy%E2%80%99s-theology-of-the-cross

- https://peacefulscience.org/articles/100-year-old-tree/

- http://biologos.org/blogs/jim-stump-faith-and-science-seeking-understanding/toward-a-theology-of-astronaut-beavers

Oct 23, 2016

Oct 13, 2021

Feb 25, 2026