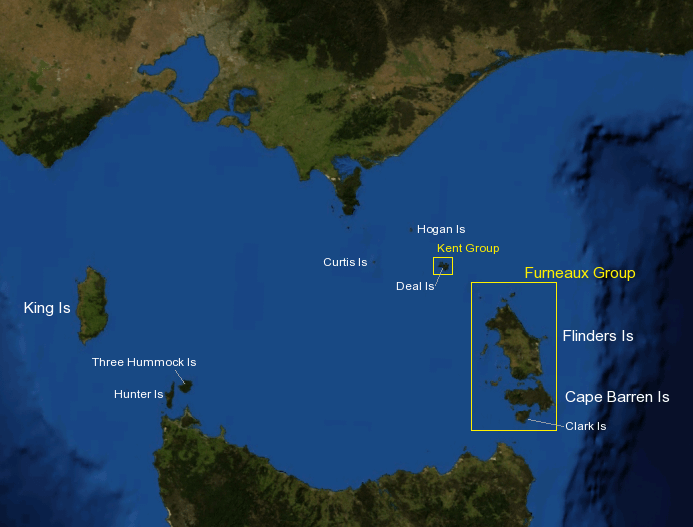

How does the isolation of Tasmania impact recent universal ancestry?

The Genealogical Adam and Eve tests a provocative hypothesis, using this hypothesis to probe the limits of scientific understanding. Consider everyone who lives across the globe from AD 1 onward. It is possible, or even likely, that everyone in this group is a genealogical descendent of a couple in the Middle East that lived just 6,000 years ago?

Our best estimates of universal ancestry tell us the answer is yes. If Adam and Eve were real people in a real past, then they are ancestors of all of us, even if they lived just 6,000 years ago.

Science progresses as we diligently work to falsify our hypotheses. We question all our findings, especially when they are surprising. The simulations on which the estimate is based assumes that it is possible for migrants to access all parts of the globe, at least in principle. In chapter 6, I try to falsify this assumption. I do this by considering, separately, isolated islands (Hawaii and Easter Island), the Americas, the Andaman Islands, Australia, and Tasmania.

In the case of Tasmania, I find that the assumption may not be valid from 6,000 years ago to AD 1, but we cannot say for sure. It is possible that Tasmania was entirely isolated during this time. Though there is evidence of isolation, we struggle to evidentially demonstrate that there was precisely zero immigrants, rather than almost zero immigrants. For this reason, there is legitimate dispute about the genealogical isolation of Tasmania.

For two reasons, the theological conversation, however, can move ahead as the scientific debate continues.

- Moving Adam and Eve slightly more ancient takes the Tasmanian objection off the table entirely.

- If nearly universal ancestry is sufficient for theology, then Tasmanian isolation would not matter any way.

Even if there was precisely zero immigrants, Adam and Eve at 6,000 years would still be nearly universal ancestors of everyone by AD 1, ancestors of everyone except those of solely Tasmanian descent. Nearly universal ancestry, 99.99% of the world population at AD 1, may be all that theology requires.

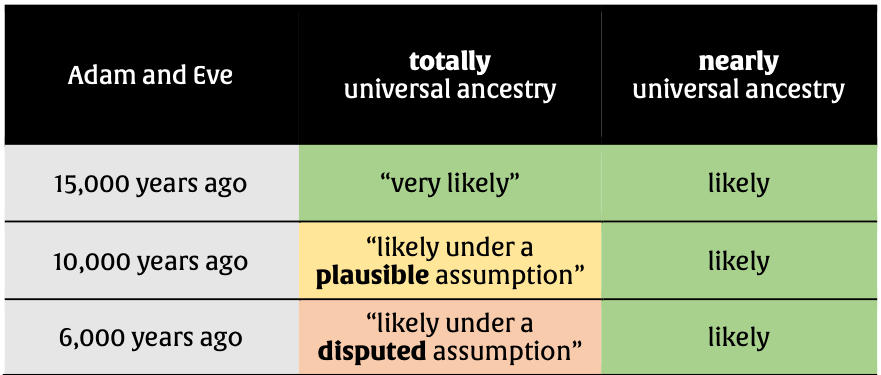

The figure visualizes how I summarize my findings. My precise scientific argument is nuanced and complex. It is possible the case by which I arrived at this conclusion can be refined. The scientific reviewers of the book agreed that this conclusion is sensible. Of course, it is possible these dates will be refined with further work. Consistent with the conclusion that this is a disputed assumption, some scientists contend Tasmania was totally isolated from before 6,000 years ago to AD 1. After they read the book, I invite scientists to submit any errors they find for review. All substantive errors will be identified and corrected. I hope to correct the typos too.

Nearly universal ancestry might be good enough for theology, because the doctrine of monogenesis is not stated with scientific precision. If our theology grants equal human rights and dignity to people outside the Garden, there is no reason to be concern.

Of note, there is no one of solely Tasmanian ancestry among us any more. It is worth remembering why they are gone. A string of horrific abuses pushed them to extinction under European colonization.

Theologians might understand the deplorable history of Tasmanian colonization in one of two different ways. In this history, perhaps, we glimpse an echo of our distance past, seeing how Adam and Eve’s fallen dominion destroyed and subsumed people from outside the Garden. Or, alternatively, we see the familiar story of Adam and Eve’s lineage, warring against itself. Whatever our understanding of Adam and Eve, or where we place them in history, we should all agree the evil done to Tasmanians was evil. Not just wrong; it was truly evil.

So what theology might grant equal human rights and dignity to people outside the Garden? I offer several options throughout the book (chapters 11 and 14, pp. 205-206). I look forward to seeing how theologians develop these ideas and add more options of their own. This, in fact, is part of the grand conversation my book aims to foster.

There is also a fascinating conversation to follow in science. We should be eager to learn more, exploring what science discovers here. We should welcome questions about the certainty of findings here too. How quickly did the seas rise? What was the weather like thousands of years ago in the Bass Strait, the gap between Tasmania and Australia? How helpful is the broken bridge of islands to Tasmania? How long can oral history keep knowledge of long lost lands alive? What does the genetic data tell us?

The question of Tasmania is part of the grand conversation of origins too. Were they totally isolated for 10,000 years? Rigorously considering this question invites us deeper into science. Here, let us wonder together about what we know, how we know it, and the limits of our knowledge. Maybe ancient DNA will one day unlock the puzzle. Perhaps a philosopher might “untangle the epistemological knot.”

As we welcome more of society into science, may the conversation around this question grow.

References

- https://peacefulscience.org/books/genealogical-adam-eve/

- https://asa3.org/ASA/PSCF/2018/PSCF3-18Swamidass.pdf

- https://peacefulscience.org/pdf/genealogical-adam-eve-errata-jan2021.pdf

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aboriginal_Tasmanians#After_European_settlement

- https://www.discovermagazine.com/the-sciences/ten-thousand-years-of-solitude

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bass_Strait

- https://www.sapiens.org/language/oral-tradition

Dec 13, 2019

Dec 30, 2021

Mar 2, 2026