Scientific Confidence vs. Scientific Certainty

Earlier this year, I received an email from Dr. Richard Buggs, who is a plant genome biologist working in the UK. Dr. Buggs had been reading Adam and the Genome, the book that I co-authored with New Testament scholar Scot McKnight that came out in February. Now I’m typically running behind on my email inbox at the best of times, and a reply to Dr. Buggs was clearly not going to be a note that I could dash off in a spare few minutes. And so I left the email unanswered – sorry Richard, if I may call you that – and after a while I forgot about it. Not surprisingly, and completely understandably, Dr. Buggs assumed I wasn’t going to respond, and posted the email on his webpage as an open letter. He provides the context as follows:

A few months ago, I was reading a new book by Dennis Venema and Scot McKnight entitled Adam and the Genome. I was surprised to find a claim within the book that the past effective population size of humans has definitely never dropped below 10,000 individuals and that this is a fact of comparable scientific certainty to heliocentrism. I emailed Dennis Venema, the biologist author of the book, to query this. Unfortunately, he has not yet responded. I therefore remain unconvinced that it is a scientific impossibility for human beings to have all descended from a single couple. If I am wrong, though, I would like to know.

Buggs’s concerns were then picked up by the Intelligent Design community: they were featured by the Discovery Institute, shared by Stephen Meyer on Facebook, and thereafter picked up by a number of evangelical news agencies. Suddenly a lot of people wanted to know what I had to say about this. Buggs was also clear about his motivation for contacting me. He is concerned that I might be overstating the scientific case for a large human ancestral population size to the detriment of my Christian audience:

I wanted to let you know that in my view you seem to be on very shaky ground here, and in danger of alienating Christians from science on the basis of a wrong interpretation of the current literature… I would encourage you to step back a bit from the strong claims you are making that a two-person bottleneck is disproven.

So, is there a genetic case to be made for Adam and Eve as the sole genetic progenitors of all of humanity? Have I overstated the scientific evidence to exclude this possibility? Note well: the question is not “were Adam and Eve historical individuals?” That is a question that science is not equipped to answer, as I discuss in the book. Science can tell us about our past population sizes, but it cannot weigh in on the historicity of any individuals within that population. Within the BioLogos tent, there are a range of views on Adam and Eve. What Buggs is asking here is whether Adam and Eve could have been the sole genetic progenitors of the entire human race.

To address this question, let’s take a close look at what Dr. Buggs discusses in his email (and for those who have not read it yet, I suggest reading it in its entirety before continuing here). I also note that I quite appreciate the gracious tone in which the letter was written. I don’t agree with Buggs, but I will endeavor to answer in a similarly constructive way.

The first issue I’d like to tackle is a minor one in some ways, but a significant one in others. I agree with Buggs that science has not “disproven” that humans could have descended uniquely from just two people (and also I’m acutely aware that this last sentence is particularly ripe for selective quoting). In the same breath, I also don’t think that science has “disproven” geocentrism – the idea that the earth is the immobile center of the universe. I actually spend a good deal of time in Adam and the Genome discussing what science is, and how it works as a powerful, yet limited, way of knowing. Science offers us converging lines of evidence for ideas about the natural world we have not yet rejected through repeated experimentation – but everything in science is held, at least in some sense, tentatively. Even the things we consider the most certain in science could be rejected in light of new evidence – even a sun-centered solar system. I put it as follows in Adam and the Genome, after a lengthy discussion of the evidence for common ancestry of humans and other species, and a large ancestral human population:

As our methodology becomes more sophisticated and more data are examined, we will likely further refine our estimates in the future. That said, we can be confident that finding evidence that we were created independently of other animals or that we descend from only two people just isn’t going to happen. Some ideas in science are so well supported that it is highly unlikely new evidence will substantially modify them, and these are among them: The sun is at the center of our solar system, humans evolved, and we evolved as a population (55).

In other words, we have multiple, interlocking, converging lines of evidence for each of these three claims, and we can have great confidence that new scientific evidence will not substantially change our views. (Also, note that I do not claim this certainty for the oft-cited ~10,000 figure, as Buggs seems to imply, since future estimates could possibly shift this value a bit. What I’m saying is that new evidence isn’t going to get us from a population to a pair). Is it proven? No, proof is for alcohol and mathematics, as the saying goes. Can you take it to the bank? Absolutely. It’s a subtle difference, but an important one.

With that out of the way, we can now attend to the specific points that Buggs presents as a challenge to our confidence that the ancestral human population was a large one.

Heterozygosity and population bottlenecks

One objection raised by Buggs centers around the concept of heterozygosity. In many organisms, such as humans, genes have two copies – one we receive from our mothers, and one from our fathers. The fact that we have two copies of each gene means that those copies can be slightly different. Different variants of a gene are called “alleles” – and if, for a given gene, someone has two different alleles, they are said to be heterozygous for that gene. Heterozygosity is just a measurement of how many individuals in a population are heterozygous for a particular gene. It is also possible to estimate the average heterozygosity of a population by looking at heterozygosity at multiple genes, or even across the entire genome. It is this measurement that Buggs has in mind when he offers the following critique:

To get more specific, I think you are mistaken when you say this:

“If a species were formed through such an event [by a single ancestral breeding pair] or if a species were reduced in numbers to a single breeding pair at some point in its history, it would leave a telltale mark on its genome that would persist for hundreds of thousands of years— a severe reduction in genetic variability for the species as a whole.”

It is easy to have misleading intuitions about the population genetic effects of a short, sudden bottleneck… a single pair of individuals can carry a great deal of heterozygosity with them through a bottleneck, if they come from an ancestral population with high diversity, and they will pass that on to the population they found, so long as it grows rapidly.

Buggs is correct that a population passing through an extreme bottleneck – and a bottleneck of two is as extreme as it gets for a sexually reproducing species – will on average retain a sizeable proportion of its heterozygosity (perhaps 75%, on average, if conditions are right). This is not the same thing, however, as retaining a significant proportion of the population’s genetic diversity. A bottleneck (and especially one as extreme as a reduction to two individuals) would greatly reduce genetic diversity, even if heterozygosity is not hugely impacted. The reason for the apparent discrepancy is that heterozygosity is a very limited way to measure genetic diversity. Let’s use an example to help us understand things.

Imagine a fictional population (population one) where there are only two alleles present for a particular gene – the “dee” gene. Let’s call the two alleles “d1” and “d2” as a way to distinguish them. In this population, half of the individuals are heterozygous – “d1d2” – they have one copy of each of the two variants. The other half of the population is split between the two ways of being homozygous, or having two identical alleles: one quarter of the population is “d1d1”, and one quarter is “d2d2”. This population thus has a heterozygosity value of 0.5 for this gene, since half of the individuals are d1d2.

Now imagine a second population (population two). In this population, there are 10 different alleles of the “dee” gene: d1, d2, d3, etc – all the way up to d10. Depending on how rare (or common) each of these alleles is in the population, this population could also have a heterozygosity value of 0.5 for this gene. In this case, the heterozygosity value would be the sum of all the different heterozygous individuals (and there would be a large number of different possibilities). For example, we would now have individuals that could be d1d2, d1d3, d1d4, and so on for all the different combinations. Only homozygous individuals would be excluded from the heterozygosity score – d1d1, d2d2, d3d3, and so on. Based on the frequencies of the different alleles, it’s entirely possible to have the heterozygosity value for the “dee” gene in population two also equal 0.5.

And here we see the challenge of using heterozygosity scores to estimate genetic diversity. Despite their equal heterozygosity scores, population two is much more genetically diverse than population one. It has 10 alleles where population one has only 2. By using techniques that capture this diversity, we would correctly infer that population two has a much larger ancestral population size than population one does. All of those different alleles ultimately trace back to different ancestors that had mutation events to produce them.

Let’s carry this thought experiment a little further. Now imagine that population two undergoes an extreme genetic bottleneck – a reduction to only one breeding pair. For argument’s sake, let’s say these two individuals happened to be genetically d1d2 and d1d2 (I’ll choose these for convenience, but the same point could be made with any two individuals selected at random). This population would expand after the bottleneck, but now alleles d3 through d10 have been lost. The new population could also easily have a heterozygosity value of 0.5, even though it has had a severe reduction in genetic diversity in the form of lost alleles. Note well: a population can pass through a bottleneck with little or no effect on heterozygosity, but with a dramatic reduction in genetic diversity. So, Buggs’s noting of the former – that populations can retain heterozygosity – does not establish that humans could have passed through a bottleneck of two with their genetic diversity only marginally affected. Our lineage would have been affected by losing alleles.

The key here is that one individual can only have at most two alleles of any gene. A population reduction to one breeding pair would mean that at most, four alleles of a given gene could pass through the bottleneck – in the case where both individuals are heterozygous, and heterozygous for different alleles. The population would then have to wait for new mutation events to produce new alleles of this gene – a process that will take a significant amount of time. Since this would happen to all genes in the genome at the same time – a reduction to a maximum of four alleles – we would notice this effect for a long time thereafter as genetic diversity was slowly rebuilt across the genome as a whole.

So, a bottleneck to two individuals would leave an enduring mark on our genomes – and one part of that mark would be a severe reduction in the number of alleles we have – down to a maximum of four alleles at any given gene. Humans, however, have a large number of alleles for many genes – famously, there are hundreds of alleles for some genes involved in immune system function. These alleles take time to generate, because the mutation rate in humans is very low. This high allele diversity is thus the first indication that we did not pass through a severe population bottleneck, but rather a relatively mild one (estimated, as we have discussed, at about 10,000 individuals by current methods).

Another effect that a bottleneck to two individuals would produce is that there would be no rare alleles after the bottleneck. All alleles would have a frequency of at least 25%. As the population expanded after such an event, those alleles would stay common, and only new mutations would produce less common alleles. What we observe in humans in the present day is that many alleles are rare – even exceedingly rare. The distribution of alleles in present-day humans looks like it comes from an old, large population – not one that passed through an extreme bottleneck within the last few hundred thousand years, which is when our species is found in the fossil record. Thus the observation that we have many alleles of certain genes and the distribution of allele frequencies both support the hypothesis that humans come from a population, rather than a pair.

In the next part of this reply, we’ll look at a method that looks beyond alleles at a single gene to multiple genes simultaneously. Such a method can detect bottlenecks with great power, because it examines patterns of alleles in groups. As we will see, this method also fails to find a bottleneck below about 10,000 individuals for our species, adding to the evidence that our lineage was never reduced from a population to a pair.

References

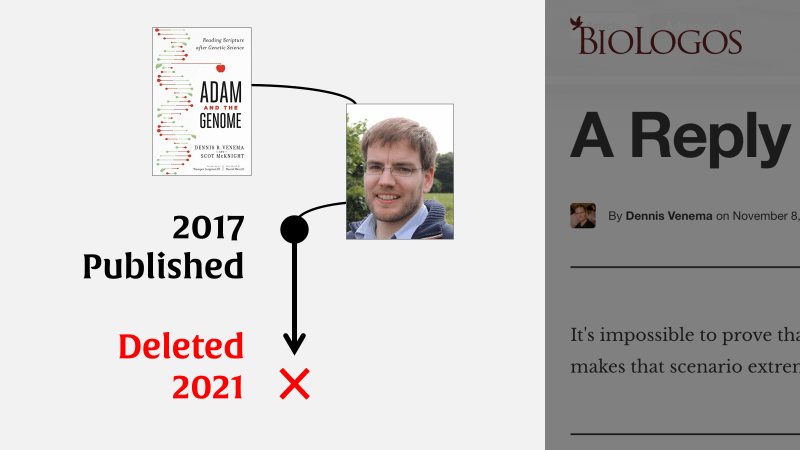

Venema, D.R. and McKnight, S (2017). Adam and the Genome: Reading Scripture After Genetic Science. Brazos, Grand Rapids.

Adam, Eve, and Population Genetics (Blog Series)

S. Joshua Swamidass, Three Stories on Adam, Peaceful Science, 2018. https://doi.org/10.54739/3doe

S. Joshua Swamidass, BioLogos Deletes an Article, Peaceful Science, 2021. https://doi.org/10.54739/rv8k

The article series in the references was deleted from the BioLogos website in June 2021.

May 2, 2022

Nov 3, 2017

Mar 13, 2026