Coalescense and Population Estimates

In the first part of my response, I tackled the concern that Dr. Buggs raised about the ability of heterozygosity to survive a population bottleneck. I intended to continue on to his concerns about linkage disequilibrium (LD) models in this post. However, following on from that post, dialogue between myself, Dr. Buggs, and others on the BioLogos Forum made it clear to me that an additional discussion about allele-based methods for estimating population sizes might be useful.

A non-technical summary

Unfortunately for a lay audience, this conversation gets pretty technical in a hurry–especially since Dr. Buggs is a biologist and is critiquing my work in Adam and the Genome at a high level of detail. A detailed critique is fair game, of course. I’ve often said that in many ways peer review starts rather than ends with publication—and I’ve certainly offered technical, critical reviews of books from other perspectives. Sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander.

Part of Dr. Buggs’s critique, as I understand it, is his doubt that a bottleneck to two people has ever been explicitly tested by population genetics methods. Moreover, he argues that a sudden reduction to two people followed by a rapid population expansion could in fact be missed by the methods I base my conclusions on. If so, then my confidence that humans have never dipped down to a population of two would be overstated, and there might be room for reasonable doubt that the science is as settled as I claim it to be.

In the first part of my reply, we discussed heterozygosity and saw that it can be maintained even as many alleles are lost during a bottleneck, reducing the genetic variation within a population. In this part of my reply, I’ll move on to discussing how allele-based methods are used to estimate population sizes, and sketch a brief history of how they have been applied to humans. In the process we’ll see that Dr. Buggs’s hypothesis—a severe bottleneck in human history—has indeed been tested and rejected by scientists. We’ll also learn about coalescence, which will not only help us understand allele-based methods in general, but also prepare us for a later discussion of a particular method of estimating population sizes that is of concern to Dr. Buggs: the pairwise sequentially Markovian coalescent (PSMC) method.

But, let’s walk before we run. We’ll start with an introduction to the concept of coalescence, and methods that use it to estimate population sizes.

Coalescent-based methods: a primer

When we examine a given gene (or a DNA region in between genes) in present-day humans we often note different DNA sequence variants that are present–i.e. different alleles. When we compare any two alleles to each other, we can see how many differences there are between them. Usually these changes are one or more single DNA letter differences, or perhaps insertions or deletions of one or more DNA letter. Sometimes the changes are more extreme–but in either case, we can deduce how many DNA mutation events separate any two alleles. Working back in time in a population, eventually we will work back through each of the mutation events that caused the changes, and the two alleles will eventually become the same–i.e. they will coalesce.

Taking into account estimates of mutation frequency it is possible to estimate how long ago any two present-day alleles coalesce with each other. This is called the Time to the Most Recent Common Ancestor, or TMRCA, for any pair of alleles.

When looking at a number of alleles in a present-day population, we will see a range of TMRCA values—some pairs of alleles will be quite similar to each other, meaning that they are separated by one or perhaps only a few mutations—and thus coalesce with each other recently in the past. Other allele pairs will have many more differences, and coalesce further back in time. For a gene or DNA region with many alleles in present-day humans, we can do pairings of all the different possible alleles, and produce a range of TMRCA values for what we observe in the present day. In this way we account for all the alleles we observe in the present and compare them to each other in a pairwise manner.

One thing that TMRCA values can be used for is to estimate the ancestral size of the population in question at different points in its past. The probability that any two alleles will coalesce in a given previous generation (again, working back from the present) is directly related to how large the population is. Remember that mutation events are rare, because the mutation rate is very low. Thus the probability of coalescence is mostly due to the probability of alleles being inherited from the same ancestor (even as rare mutations are also occurring during this process). As the number of ancestors drops–i.e. the population size decreases—the probability of coalescence increases. As the population size increases, the probability of coalescence drops. Thus, when a bottleneck occurs—a reduction in the population size—the probability of coalescence increases, and it increases for all genes in the genome.

Coalescence and bottlenecks

In the case of an extreme bottleneck, where the population size drops to just two individuals, many alleles will be lost. At most four alleles will make it through the bottleneck (as we discussed in the first part of my reply). What we didn’t mention then but is also relevant is that the surviving alleles also have a good probability of being lost in the generations following on from the bottleneck. In small populations, such as one expanding after an extreme bottleneck, the probability of losing some alleles just by chance is high. In the first part of my reply recall that we discussed heterozygosity – the case when there are at least two alleles for a given gene in a population. We saw that even in the most favorable conditions after a bottleneck, heterozygosity is preserved only about 75% of the time. This means that about 25% of the time, heterozygosity is lost, and that only one allele remains in the population for a given gene. If only one allele is present, then this is a coalescence point for that gene: going forward, we will have to wait for mutations to produce new alleles, and those new alleles will coalesce back to their single ancestral allele that survived the bottleneck. In the future, as new alleles are produced from the surviving allele through mutation, the new alleles will all coalesce within a few generations of the bottleneck. Their TMRCA values will thus be almost identical.

After a bottleneck, then, we will see a range of TMCRA values across the genome, once we account for all of the alleles we can find in the present day. For some genes, multiple alleles will survive the bottleneck, and their TMRCA values will thus precede it. Other genes will coalesce at the bottleneck. Other genes will coalesce after the bottleneck, since coalescence happens occasionally even without a bottleneck to increase its probability. The way bottlenecks leave a detectable mark on a genome is this: they give alleles at numerous genes the same coalescence time. Even if it is only on average around 25% of genes that coalesce at this time, this is still a large number of genes in absolute terms. The fact that they all coalesce at the same time in the past is the indication that coalescence was highly probable then—because population size was small.

Coalescent-based methods are thus an excellent way to detect bottlenecks—even really brief ones, if they are severe enough. Even a brief, severe bottleneck will still greatly increase the chances of alleles being lost, and the telltale signature of numerous genes that coalesce within a short time frame. A rapid expansion of population after a severe bottleneck can reduce this effect, but never eliminate it. On average, about 25% of genes will coalesce, and this is more than enough genes to reveal a bottleneck—even if the bottleneck was only one generation long, and followed by rapid expansion.

Since coalescence-based methods were developed, they have been used widely for investigating ancestral human population sizes. As we sequenced the human genome, we applied these methods to an increasingly large data set of allele variation from around the world. The results of these studies have consistently indicated that humans descend from a substantial population and not merely from a pair. Let’s trace a snapshot of that experimental history next.

A brief history of coalescent methods and human population size estimates

Early studies on human variation, prior to the human genome project (HGP) were restricted to working with alleles of single “genes”, or more properly, short stretches of DNA that included a gene but also some DNA around it. These studies depended on the researchers actually going out and sequencing a large number of people for this specific region, and then making sense of the allele diversity they found.

For example, this early paper looks at a few such genes for which data was available at the time and concludes this (from the abstract, with my emphases):

Genetic variation at most loci examined in human populations indicates that the (effective) population size has been approximately 10(4) (i.e., 10,000) for the past 1 Myr and that individuals have been genetically united rather tightly. Also suggested is that the population size has never dropped to a few individuals, even in a single generation. These impose important requirements for the hypotheses for the origin of modern humans: a relatively large population size and frequent migration if populations were geographically subdivided. Any hypothesis that assumes a small number of founding individuals throughout the late Pleistocene can be rejected.”

What is interesting to note is that at this time in the scientific literature, a severe bottleneck in the ancestral human population was considered a possibility to be tested—even the idea that a very sudden bottleneck might have taken place. In these early dates of human population genetics research, it was an open question if humans came from a very small founding population. In this paper, however, the authors conclude that such a bottleneck is ruled out by the evidence: there is simply too much variation in present-day populations that coalesces further back than one million years ago (1 Myr).

Later pre-HGP papers were in agreement with these early results. For example, this paper looked at allele diversity at the PHDA1 gene, and reports a human effective population size of ~18,000. Similarly, studies of allelic diversity at the beta-globin gene found it to indicate an ancestral effective population size of ~11,000, and conclude that “There is no evidence for an exponential expansion out of a bottlenecked founding population, and an effective population size of approximately 10,000 has been maintained.” They also state that the allelic diversity they are working with cannot be explained by the recent population expansion that characterizes our species—the alleles are too old (i.e. they have TMRCA values that are too large) to be that recent.

It is in this timeframe that a coalescence study investigating allelic diversity of a different kind was published. It looks at allelic diversity of Alu insertions. Alu elements are transposons—short snippets of autonomous, mobile DNA that can replicate and move within genomes—that generate “alleles” where they insert into a chromosome. Generally, if an Alu is present, that’s an allele, compared to when an Alu is absent (the alternative allele). This study also acts as an independent check of other coalescence-based studies because it does not depend on a forward nucleotide substitution rate—i.e., the standard DNA mutation rate, since Alu alleles are not produced by nucleotide substitutions. This paper concludes that the human effective population size is ~18,000. They also state (my emphases):

The disagreement between the two figures suggests a mild hourglass constriction of human effective size during the last interglacial since 6000 is very different from 18,000. On the other hand our results also deny the hypothesis that there was a severe hourglass contraction in the number of our ancestors in the late middle and upper Pleistocene. If humans were descended from some small group of survivors of a catastrophic loss of population, then the distribution of ascertained Alu polymorphisms would show a pre-ponderance of high frequency insertions (unpublished simulation results). Instead the suggestion is that our ancestors were not part of a world network of gene flow among archaic human populations but were instead effectively a separate species with effective size of 10,000-20,000 throughout the Pleistocene.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, we start to get into what are really human genome project papers but are focused studies on worldwide allele variation for small DNA regions, rather than genome-wide variation. For example, one paper of this type looked at allele diversity for a small region of chromosome 1. This study employs a variety of estimates of population size for this region, and concludes the following (my emphases). Note that once again, the hypothesis of a severe bottleneck is tested and rejected:

An average estimate of 12,600 for the long-term effective population size was obtained using various methods; the estimate was not far from the commonly used value of 10,000. Fu and Li’s tests rejected the assumption of an equilibrium neutral Wright-Fisher population, largely owing to the high proportion of low-frequency variants. The age of the most recent common ancestor of the sequences in our sample was estimated to be more than 1 Myr. Allowing for some unrealistic assumptions in the model, this estimate would still suggest an age of more than 500,000 years, providing further evidence for a genetic history of humans much more ancient than the emergence of modern humans. The fact that many unique variants exist in Europe and Asia also suggests a fairly long genetic history outside of Africa and argues against a complete replacement of all indigenous populations in Europe and Asia by a small Africa stock. Moreover, the ancient genetic history of humans indicates no severe bottleneck during the evolution of humans in the last half million years; otherwise, much of the ancient genetic history would have been lost during a severe bottleneck.

Accordingly, we can see from these studies that Dr. Buggs’s hypothesis – that present-day human allelic variation could be consistent with a brief bottleneck to just two individuals—has indeed been tested in the literature and rejected. No such bottleneck is supported within the last 500,000 years or more, far longer than our species has existed in the fossil record. Present-day humans have too many alleles that are more ancient than a severe bottleneck during this timeframe would allow. Moreover, no evidence of a severe bottleneck as revealed by grouped TMRCA values—i.e. a number of genes showing clustered coalescence times—is present in human DNA over this same period. Humans dip down to a population size of about 10,000—not 2.

References

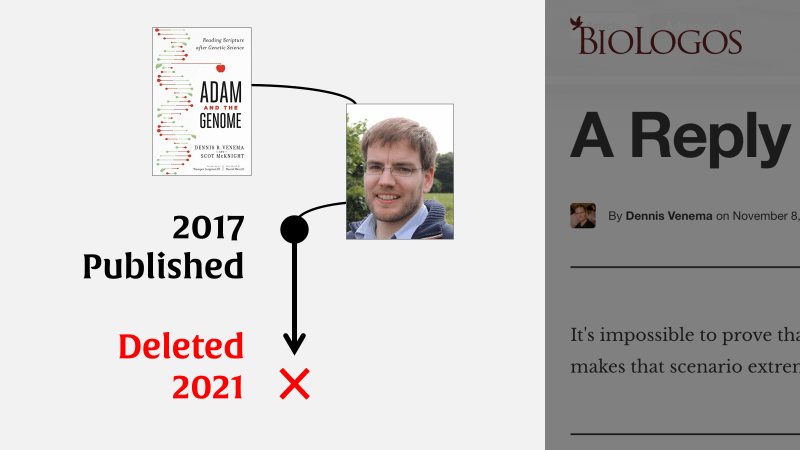

Venema, D.R. and McKnight, S (2017). Adam and the Genome: Reading Scripture After Genetic Science. Brazos, Grand Rapids.

Adam, Eve, and Population Genetics (Blog Series)

S. Joshua Swamidass, Three Stories on Adam, Peaceful Science, 2018. https://doi.org/10.54739/3doe

S. Joshua Swamidass, BioLogos Deletes an Article, Peaceful Science, 2021. https://doi.org/10.54739/rv8k

May 3, 2022

Nov 30, 2017

Mar 6, 2026