Excerpt from Faith Across the Multiverse by Andy Walsh, © 2018 by Hendrickson Publishers, Peabody, Massachusetts. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

The military training of these children [in Ender’s Game] even goes so far as to remove them from Earth and train them on orbital platforms in space. A central feature of this training is the Battle Room, a zero-gravity arena where squads play capture the flag against each other to hone whatever tactical edges they can find. Ender’s potential as a Battle Room warrior is initially overlooked because he is insubordinate and unimposing. But c’mon, his name’s in the title of the book, so he’s bound to have some unappreciated skill that will carry the day.

Ender’s most famous contribution to the Battle Room is an organizing principle: “The enemy’s gate is down.” Ender realized that even lateral thinking was too Earth-bound. It suggests a sideways approach to your goal within a coordinate system defined first by the up/down axis of gravity, then the forward/backward axis of movement relative to your goal. But in space, there is no strong gravitational asymmetry to orient along, so why not use your goal to define your primary axis?

battle room sequences of the Ender’s Game movie really captured the freedom and need for reorientation of the low gravity environment.

This reorientation of the Battle Room helped his squad in several ways. Advancing toward their goal suddenly seems as natural as falling down. They now have a common reference system in an environment that did not readily offer one. The soldiers were freed from thinking about their movement in earthbound terms that created artificial restrictions irrelevant to space combat. By comparison, think about how the large ships in Star Wars or Star Trek often engage each other the way naval vessels would, as if there is still a plane in space that everything must move along like the one defined by the surface of the oceans.

By providing this new frame of reference, Ender acknowledges two realities. The first is that he and his classmates were being held back by rules that made sense on Earth but were incoherent in space. The second and more subtle one is that casting aside those rules for complete freedom wouldn’t be an improvement. In order for his squad to work together, they would still need a framework in which to operate. When they found the old framework didn’t match the new context, they didn’t ditch rules altogether; they found ones that fit the new context.

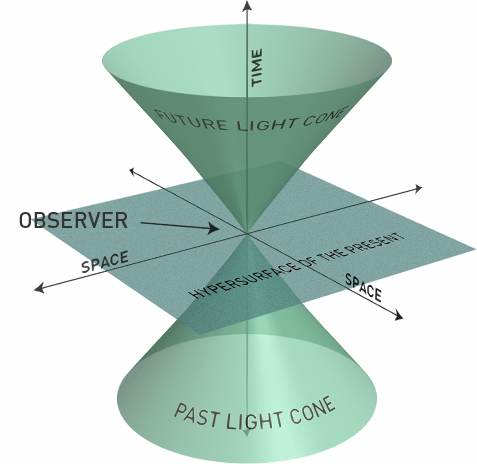

A similar paradigm shift occurred in physics as a result of studying light. For centuries, space and time were considered fixed, which is to say that everyone measuring the dimensions of the same object would get the same sizes and everyone measuring the duration of an event would get the same time. All speeds on the other hand would be relative; how fast you observed an object moving would depend on how fast you yourself were moving. The only speed that everyone would measure the same is infinite speed. Whether infinite speed is physically possible is a separate question, but you can use the equations of motion from this model of physics to work out mathematically that infinite speeds are the only ones with this property.

Studying light, however, wound up challenging this conclusion. It’s not that the calculations were being done incorrectly, but rather that the models and equations were built on assumptions (or axioms) that did not correspond to the reality of our world. First, it was observed that light has a finite speed. This was not immediately apparent; light travels so fast that over human scales, it might as well be instantaneous. It was only when we started studying the world on the scale of the solar system and the galaxy that we could start to observe the consequences of light traveling at finite speed. The electromagnetic equations that describe light as a wave confirm this conclusion, since a wave that is everywhere all at once is no wave at all.

CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

By itself, a finite speed for light is not revolutionary. However, what we also observe is that the speed of light is measured the same by everyone, regardless of how fast they are moving. The experiments to study the æther that mediates light waves that we discussed last chapter were among these observations. In addition to failing to find evidence of æther, these experiments also failed to find any evidence that the speed of light depended on relative motion the way other speeds do. This was perhaps the most famous and most significant example of the value of negative results, of knowing with precision what we don’t believe about the universe. If we don’t believe that the speed of light depends on relative motion, then something else about our model of physics must be wrong as well.

Ultimately, the observation that the speed of light is both finite and fixed led to a new framework for understanding space, time and motion called special relativity. No, wait, come back! You survived the quantum physics chapter; you can handle this one as well. I know special relativity, along with its cousin general relativity, has a reputation for mental gnarliness rivaling that of quantum physics. This is at least partly because both theories are counterintuitive, being based on observations at scales far removed from daily experience. Quantum physics comes into play when things get very small, and as we noted earlier, special relativity was only developed once we started considering a galactic scope. But this is precisely why these theories are valuable to us for expanding our conceptual repertoire for thinking about God.

Likewise, moving Ender and his friends to space proved fruitful and necessary to understanding how to deal with the Formics. Expanding their conceptual horizons by learning to operate in a context other than the surface of Earth enabled them to conceive of tactics and strategies that would never have occurred to the greatest military minds of the previous generation. Ultimately, Ender’s perspective shifted so drastically that he was able to entertain the possibility that the Formics weren’t even the bloodthirsty enemy they seemed to be.

Broadening one’s horizons and changing one’s perspective have positive and negative associations. On the one hand, doing so can spark creativity or expand our capacity for empathy. On the other, there is a concern, at least in Christian circles, that one can go so broadly into a pluralistic experience as to wind up in pure relativism. And since special and general relativity have relativity in their names and spread in popular awareness around the same time as postmodernism, I can see where those topics in physics might make some Christians uneasy, especially when applying them via analogy.

While special relativity predicts that the outcome of certain measurements will depend on the context of the measuring, it is also a theory with absolutes. We are not giving up a more absolute model for a more relative one, we are simply changing which quantities are absolute and which are relative. And we are doing so because the model better reflects the reality in which we live, which provides an absolute point of reference of a different sort. At the same time, we also cannot completely escape relative motion. It is a part of everyday experience that is consistently modeled in special relativity and the theories that preceded it.

References

Card, Orson Scott. Ender’s Game. (New York: Tor Books 1985)

Ender’s Game. Directed by Gavin Hood, performances by Asa Butterfield, Harrison Ford, and Hailee Steinfeld. (Lionsgate, 2013)

Seymour, Mike. “Ender’s Game: how DD made zero-g,” https://www.fxguide.com/fxfeatured/enders-game-how-dd-made-zero-g/ published November 4, 2013, accessed December 29, 2021

Penrose, Roger. The Road to Reality: A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe. (London: Jonathan Cape, 2004)

Kaku, Michio. Hyperspace: A Scientific Odyssey Through Parallel Universes, Time Warps, and the 10th Dimension. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994)

Lederman, Leon M. and Hill, Christopher T. Symmetry and the Beautiful Universe. (Amherst: Prometheus Books, 2004)

Dec 29, 2021

Feb 5, 2022

Feb 25, 2026