Excerpt from Faith Across the Multiverse by Andy Walsh, © 2018 by Hendrickson Publishers, Peabody, Massachusetts. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

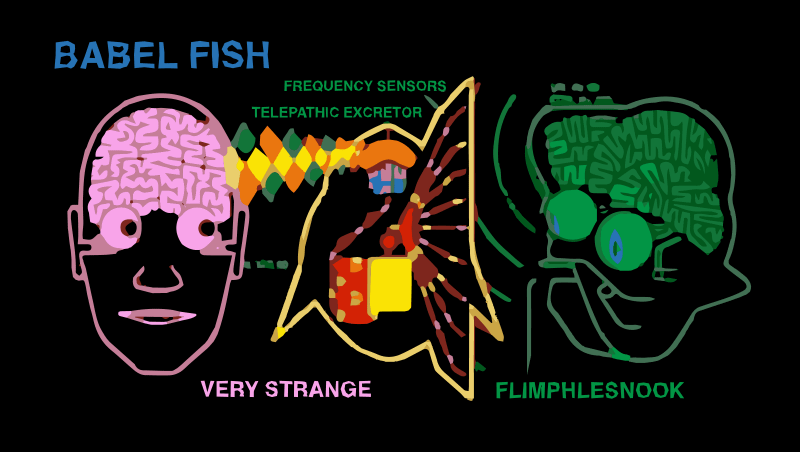

The Babel fish is a small, bright yellow fish, which can be placed in someone’s ear in order for them to be able to hear any language translated into their first language.”

I have a particular affinity for Babel fish ( translator fish from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy) because I’ve spent much of my career filling a similar role within the sciences. I wound up learning a lot of math for a graduate student in microbiology, so I spent a lot of time teaching statistics to my fellow biologists. That helped me get a postdoctoral fellowship facilitating collaboration between computer scientists and biologists by pointing out where their ideas overlapped and, just as importantly, where they thought they were talking about the same thing because they were using the same word, but they actually had very different concepts in mind. And now I work for a public health software company, translating between public health users and software engineers and teaching everyone a little math and basic biology along the way.

My favorite word from those cross-discipline conversations is “vector.” To someone with a math or physics background, a vector is a quantity associated with a direction, such as wind velocity. To a computer scientist, a vector is a collection of data elements that may or may not be numeric. To a molecular biologist, a vector is a circular DNA molecule used to add external gene functionality to a cell. And to an infectious disease specialist, a vector is an animal that carries a disease, like a mosquito or a rat. Many folks are aware of the different, domain-specific meanings, but even experienced interdisciplinary researchers can get caught thinking about numbers while their colleagues mean ticks. And so having a “multilingual” Babel-human like me around helps keep conversations on track.

Language barriers are also a common problem in science fiction. Aliens should speak a variety of languages. Making every character a polyglot is unrealistic, and constant fumbling over language barriers would get in the way of good storytelling. Conjuring Babel fish or Universal Translators or literal magical spells simultaneously acknowledges and shelves the issue.

Translation is not science fiction. Making it instantaneous and perfectly accurate is the unrealistic part; sometimes we have to wait for the translation. Translating is not just a matter of swapping one word at a time for its equivalent, which is how something like the Babel fish apparently works. Anyone who has studied a foreign language has encountered idiomatic phrases whose meaning is not captured by a word-for-word translation. For example, I made my German teacher giggle while practicing pet-related vocabulary because my grammatically correct and word-by-word accurate Ich habe einen Vogel (“I have a bird”) was simultaneously an admission to having bats in my belfry, so to speak.

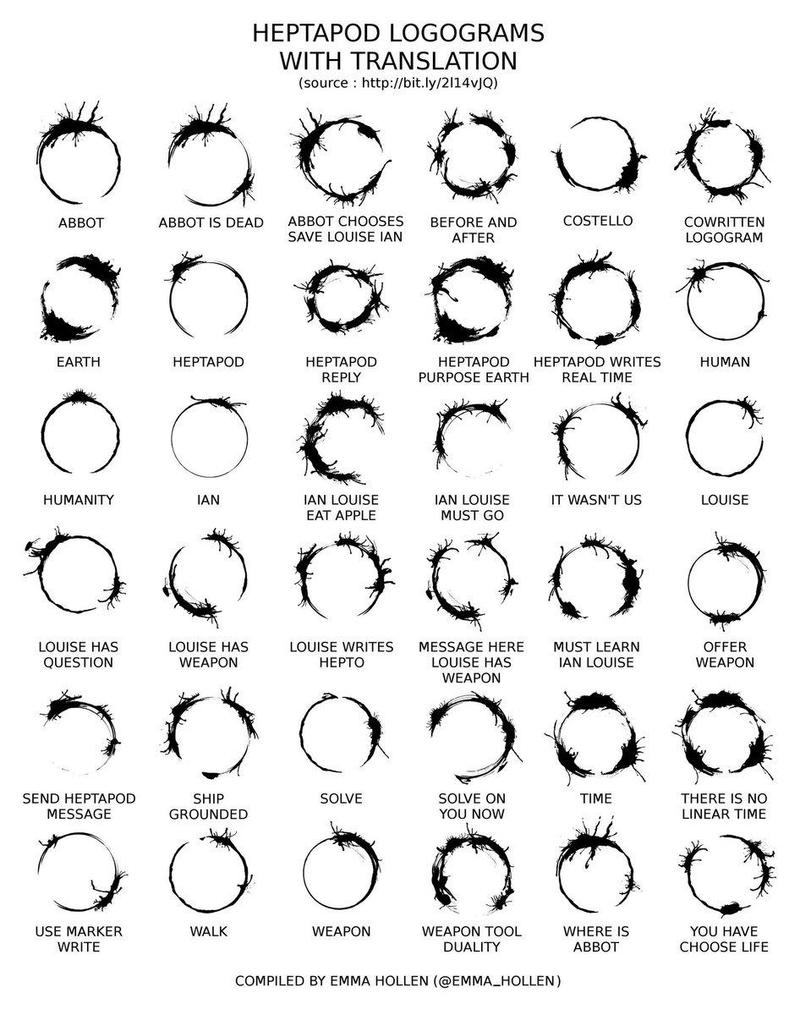

created an alien language to be deciphered by Louise Banks, a linguist in the film.

Unlike most science fiction, the film Arrival digs deep into matters of translation. Aliens arrive on Earth for the first time and linguist Louise Banks leads a team to establish communication with them. Learning individual vocabulary words and idioms is challenging enough without a dictionary, but Louise recognizes the possibility of even deeper problems. The aliens’ experience may be so different from ours that they think about different concepts. Do they have a notion of war? Do they distinguish between tools and weapons? These are the immediate concerns of world leaders wondering if these aliens come in peace, but Louise eventually discovers that the conceptual gulf runs deeper still.

Even human languages don’t overlap fully in terms of the concepts they can represent. If we give it any reflection at all, we probably think of our languages as complete. Sure, maybe we need to invent new words when we invent new technologies, like the telephone or Facebook. But for regular ideas, surely we must have the words to say what needs to be said. Only, how would we talk about the things our language lacks the vocabulary to describe?

The Germans have a very useful word: Weltschmerz. Translating the parts of this compound noun into English yields “world pain” but a more faithful translation might be the feeling one experiences upon recognizing the divergence between reality and an ideal vision of the world. English lacks an equivalent word; the closest match might be Charlie Brown’s exasperated “Good grief!” But even that is more of a groan, signifying Charlie Brown is experiencing Weltschmerz without actually naming it. All languages differ in which concepts they can readily express with a single word or common idiom; even fundamental features like the number and kind of verb tenses can vary. What is easy or hard to express in a given language influences how speakers of that language talk and possibly think.

Another example that might be more familiar to Bible readers is love. We can say a lot about love in English; poems, songs, and tales of love abound. Love is such a fundamental part of the human experience that we might think it would be a foundational part of any human language. In fact, the ancient Greeks had several words to differentiate experiences we lump together as love. These include the familial bond between siblings, parents, and relatives; the brotherly affection shared by comrades-in-arms; and the romantic or physical connection that we generally mean when we say one is “in love.”

Most of the time English speakers don’t consciously experience a deficiency or limitation in their language regarding love. We blithely say “I love you, my dear” and “I love you, dad” and “I love you, man” and “I love you, delicious chimichanga” and generally everyone knows what we mean. But sometimes we don’t say “I love you” when maybe we should. Perhaps we sense our feelings for our spouse are not the same as our feelings for our children but we lack the language tools to express that nuance succinctly.

In Arrival, Louise Banks addresses this conceptual gap between her language and the aliens’ by combining written language with demonstrations. She and her team act out the words and sentences as they speak and write them. In this way, they build shared experiences with the aliens so that their communication has something to reference. Without that experience, the two parties might wind up using the same words but internally connecting them to very different concepts. As an example, she brings up the Sanskrit word गविष्टि, which some linguists translate as “an argument” while she prefers “a desire for more cows.”

References

Adams, Douglas. The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. (London: Pan Books, 1979)

Rhodes, Margaret. “How Arrival’s Designers Crafted a Mesmerizing Alien Alphabet,” https://www.wired.com/2016/11/arrivals-designers-crafted-mesmerizing-alien-alphabet/, published November 16, 2016, accessed December 1, 2021

Arrival. Directed by Denis Villeneuve, performances by Amy Adams, Jeremy Renner, and Forest Whitaker. (Paramount Pictures, 2016)

Hofstadter, Douglas and Sander, Emmanuel. Surfaces and Essences: Analogy as the Fuel and Fire of Thinking. (New York: Basic Books, 2013)

Pinker, Steven. The Stuff of Thought: Language as a Window into Human Nature. (New York: Viking, 2007)

Christiansen, Morten H. and Chater, Nick. Creating Language: Integrating Evolution, Acquisition, and Processing. (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2016)

Dec 1, 2021

Feb 5, 2022

Feb 24, 2026