I would like to thank everyone involved inside AAR for making this year’s meeting possible, as well as Dr. Swamidass for inviting me to respond to his book. I’d also like to thank Douglas Kump for introducing me to Dr. Swamidass’s work.

Time is short so I’ll get right to it.

Swamidass’s thesis is summarized concisely early on in the book (pp. 9-10):

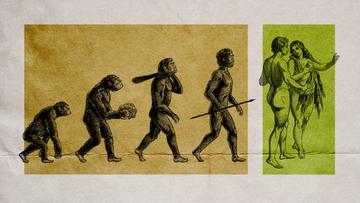

Entirely consistent with the genetic and archeological evidence, it is possible that Adam was created out of dust, and Eve out of his rib, less than ten thousand years ago. Leaving the Garden, their offspring would have blended with those outside it, biologically identical neighbors from the surrounding area. In a few thousand years, they would become genealogical ancestors of everyone….Evolution would be progressing in the mystery outside the Garden….God created everyone outside the garden through a providentially governed process of common descent, a process legitimately described by evolutionary science.

General Thoughts

To front my ultimate conclusion about the book, I don’t see any biblical passage that is fatal to the thesis. On the other hand, I also don’t see—and the author admits this openly—any explicit data in the text to support the thesis. Swamidass is therefore not making a biblical argument. He is instead offering a hypothesis that presumes (really, insists) that general revelation, the information gleaned from the study of our biology via the tools of science, be allowed to tell one story, while Scripture be allowed to tell its story. The two stories follow similar trajectories and ultimately entwine, but they are nonetheless different. They are also both coherent and true on their own terms, with respect to the truth claims they describe and put forth.

What I want to say going forward is the perspective of a biblical scholar. I’m no scientist, so I can’t evaluate the science. I’m encouraged that its science is sound based on reviews by genetics experts both favorable toward, and hostile to, the book’s religious apologetic. Consequently, I view my task today as one of interacting with the material as a biblical scholar, both to discuss how the thesis cannot be supported and how it could be supported via certain readings of the text. This is therefore a thought experiment.

Before beginning I want to put my presuppositions on the table. I should also say up front that I am positively disposed to the hypothesis, but I’m not of the concordist school. If we’re going to be serious about interpreting the biblical text in context, then we can’t seriously think God found writers in the first millennium BC who knew genetics to ensure that Genesis would give us an account of creation that accords with genetics. That is, by definition, to impose modern information and questions upon the biblical writers; that is, it is imposing a foreign context onto the text. God didn’t download modern knowledge into the heads of the writers. The Bible is not a channeled book. God did not encrypt scientific data into the biblical text without the writers’ knowledge. I harbor no suspicion that the genetic story is somehow detectable in the Hebrew text of Genesis. If modern science conveyed by the biblical text was what God intended, his choices for human authors were extraordinarily poor ones. These things should be obvious but in my experience to many they are not. We need to let the Bible be what it is—an ancient book whose ancient writers were chosen by God, writers whose cognitive environment was quite different than our own, who wrote under the providential guidance of God who, at the end of that process, approved of the outcome. We ought not impose foreign contexts on the Bible for sake of its interpretation. It is pretentious to make the Bible say such things—or criticize it for not saying what it was never intended to say. That Swamidass is not forcing the Bible to speak science is fundamentally sound and important.

Second, when I first heard of Swamidass’s book, my initial thought was whether he was aware of the dangers of racist polygenism, the idea that humanity’s races have evolved from distinct ancestral types, some superior or inferior to the others. I’ve spent a good deal of time reading in that area, so I was hoping we weren’t in for another round of that. We’re not. Those who are acquainted with the intellectual history of polygenism will know that the very concept of “race” being biologically determined and detectable is a flawed modern concept. Swamidass is an expert on genetics, so he knows the idea is nonsense. Chapter Four is devoted to debunking the idea on the basis of science. In that chapter he explicitly states:

We are all linked together in the recent past by genealogical ancestry. The human race is a single family, in a common story. Whatever our skin color, country of origin, ethnicity, or culture, we are all one family. We are one blood, one race, the human race.1

Swamidass can say this, and yet simultaneously have genealogical Adam and Eve and people outside the garden because (a) he isn’t talking about races, and (b) he argues that all people alive since as early as 1 CE (and perhaps much earlier) are humans descended from Adam and Eve. The early descendants of Adam and Eve interbred with people outside the garden. Since viable offspring came from these unions, those people were also human, though not the same as Adam and Eve. This gets us into the problem of defining the term “human,” something for which there is still no scientific consensus. Swamidass devotes an entire chapter to explaining this impasse.2

Implicit Biblical Coherence

Swamidass’s hypothesis works only if it is correct that there were people outside the garden of Eden. The idea stretches back to the fifth century BCE., married as it was to the question of whether there were other worlds before, or in addition to, this one. The notion of additional worlds takes the discussion in the direction of the subject of extraterrestrial life. The ancient history of that question as it relates to Judeo-Christian theology has been well chronicled by scholars like Michael J. Crowe.3 As theologically stimulating as I find astrobiology and the ET life question, that isn’t on the docket. The question raised by Swamidass’s book relates to other worlds, not additional ones. By this phrase we refer here to other human civilizations, or modes of communal life that fall short of what we’d define as civilization, that preceded Adam and Eve. Were there other humans before Adam and Eve and hence outside the garden of Eden?

In his biography of Isaac La Peyrère, the seventeenth century French theologian and lawyer credited with (or blamed for) vaulting pre-Adamism into the religious-intellectual battle over the discovery of people in the wake of European exploration, Richard Popkin points out there is primary source evidence as early as the second century CE for Christians debating pagans about the existence of human civilizations far older than biblical chronology allowed.4

In biblical terms, the only reasonable trajectory for the idea of people outside Eden is Genesis 4, a passage that bristles with ambiguities. The chapter opens with the births of Cain and Abel, sons of Adam and Eve (Gen 4:1-2). The text does not specifically alert us to the fact that these two boys were the first children of Adam and Eve. That is, of course, how the text has traditionally been read, and is certainly plausible. But that detail is unstated. The text is also silent in regard to other humans outside the family of Adam and Eve.

The story of Cain and Abel ensues and describes the conflict that develops between them, one that involves offerings to the Lord, where Abel’s offering was acceptable to God but Cain’s was not (Gen 4:3-7). Genesis 4:3 states that the offerings occurred “in the course of time” (Hebrew: vayehı̂ miqqēts yāmim; more literally: “And it came to pass after the end of days”). How much time has elapsed since the boys were born? We are not told.5 It is reasonable to think they are at least in their late teens or a bit more, but that notion is nothing more than a presumption. Given the lifespans described for the early generations of Adam and Eve in Genesis 5, centuries could have passed. Were Adam and Eve having other children during this time? We know they did afterward (Gen 5:4), but there is no actual commentary that they had no other children prior to the birth of Seth in Gen 5:1-3. And daughters go unmentioned until Gen 5:4, as is normative for most biblical genealogies.

The conflict between Cain and Abel leads to Cain’s murder of his brother (Gen 4:8). God confronts Cain for his sin and punishes him with banishment (Gen 4:9-12). At that point we read:

13 Cain said to the Lord, “My punishment is greater than I can bear. 14 Behold, you have driven me today away from the ground, and from your face I shall be hidden. I shall be a fugitive and a wanderer on the earth, and whoever finds me will kill me.” 15 Then the Lord said to him, “Not so! If anyone kills Cain, vengeance shall be taken on him sevenfold.” And the Lord put a mark on Cain, lest any who found him should attack him. 16 Then Cain went away from the presence of the Lord and settled in the land of Nod, east of Eden. 17 Cain knew his wife, and she conceived and bore Enoch. When he built a city, he called the name of the city after the name of his son, Enoch. (ESV)

The reader is again left to ponder certain ambiguities. How much time has elapsed between the crime of Cain and his judgment? Readers have traditionally assumed that God rebuked him and judged him immediately, and this is the most transparent reading of these verses. But again, a specific chronology is omitted. There is of course no reason for God to have delayed in addressing what Cain has done, so it seems reasonable to conclude that the other chronological ambiguities of the passage noted above are more germane to the present question of other humans outside the garden of Eden, upon which the Swamidass hypothesis depends.

In Gen 4:14, after hearing God’s judgment declared, the murderer Cain laments, “My punishment is greater than I can bear. Behold, you have driven me today away from the ground, and from your face I shall be hidden. I shall be a fugitive and a wanderer on the earth, and whoever finds me will kill me.” A face value reading of Genesis to this point has, after Cain’s murder of his brother Abel, only Cain, Adam, and Eve constituting the human population of the earth. Whom does Cain fear? Who are these other people that might kill him?

The verse could be read as suggesting there are other people outside Cain’s particular family who would hear of his awful deed and kill him on sight. That is, when Cain says today (Heb., hayyôm) you have expelled me and then worries about his fate, immediacy of the threat is assumed. A few lines later, in Gen 4:16-17, Cain departs and settles in “the land of Nod, east of Eden” where he meets a woman, marries her and then builds a city. This of course takes us to the famous “Where did Cain get his wife?” question and follows that query with another: How would Cain build a city all by himself?6

This reading has led some to conclude that there must have been humans outside the genealogical line of Adam and Eve. This reading of Genesis 4 takes advantage of the chronological ambiguities, but those ambiguities are also its own encumbrance. The “people outside Eden” approach to the passage assumes a tight chronology between Cain’s expulsion and the encounter he fears, thus subverting the argument that the other people required by the narrative must come from Adam and Eve.7

But hayyôm can be read with equal conjecture to presume that “today” is to be contrasted with the verbs “shall be” (a fugitive) and “will kill” (Cain).8 In this reading, a long stretch of time between the expulsion and the threat feared by Cain is assumed. With respect to that time period, the statement of Gen 5:4 is brought to bear, that Adam and Eve “had other sons and daughters.” This allows his potentially lethal enemies, his future wife, and the necessary co-workers in city-building to come from Adam and Eve’s subsequent children.

So, should we marry hayyôm (“today”) with the imperfect (future time) verb forms or divorce those two features of the text? It’s a matter of hermeneutical preference. As a result, we have a textual uncertainty that creates an interpretive opening for people outside Eden, but nothing more.

Dead-End Trajectories

While Genesis 4 at least gives us a possibility to ponder, other so-called biblical arguments that seek to bolster the idea of people outside Eden do not. They are internally inconsistent with respect to the early chapters of Genesis or otherwise have no merit.

We will begin with two popular speculations. First, this writer has encountered the notion that the Bible may speak of non-Adamic humans based on a presumed distinction between two Hebrew words that refer to humans: ʾādām and ʾîsh. The argument extends from the fact that the latter term can be used of animals (Gen 7:2 [twice]). Supposedly, this usage allows the argument that the lineage of Adam (Hebrew ʾādām) is distinct from other humans (or sub-humans lesser than ʾādām) described by the word ʾı̂sh. The idea that Hebrew ʾādām and ʾı̂sh are two different humanities is untenable. That the use of ʾîsh for animals in Gen 7:2 only denotes gender, and not a qualitative distinction between separate kinds of humanity is evident via a comparison of Gen 7:2 with Gen 7:3 (cf. Gen 6:19), where the two groups are distinguished as male (zākār) and female (neqēvah). Further, Gen 2:24 has Eve created “out of ʾı̂sh.” The ʾı̂sh in view is, of course Adam, which the preceding verses (Gen 2:21-23) make clear, making use of Hebrew ʾādām when doing so. Eve is thus linked to both ʾādām and ʾı̂sh, disallowing the use of the two terms as speaking of two different human lineages.9

A second speculation is that the single term ʾādām might allow for two separate human lineages, one inside the garden, the other outside. Technically, when ʾādām is prefixed with the definite article (ha-ʾādām), the form should not be translated as a proper personal name by rule of Hebrew grammar. Translations such as “humankind,” “the man,” or “this/that man” are appropriate. When ʾādām lacks the definite article, the term may be a proper personal name (Adam) or not. Besides a personal name, the term may be translated as indefinite (“a man”) or, still, generically (“humankind”).10 For our purposes, this variability has raised the question of whether the early chapters of Genesis might be re-read for two human lines, one deriving from generic or indefinite ʾādām, the other from personal name ʾādām.

This argument is part of a wider theological consideration. It has long been noted that Adam’s story has several strong parallels to the story of Israel.11 The import of the observation is that it allows the postulate, as Israel was an elect subset of humanity (the corporate “son of God” according to Exod 4:23; Hos 11:1), so might Adam be an elect subset of a wider humanity?

Whatever coherence the Adam:Israel analogy might have, applying to the question of people outside Eden is unsustainable. The “two ʾādām” strategy for doing so is undermined by Gen 5:1, where we are provided with the genealogy of Adam (no definite article on ʾādām). This genealogy is not just any man, nor of all generic humanity, but Adam. Genesis 5:1b-2 takes this form, ʾādām without the article, and links it to Gen 1:26-27, where humans are created baraʾ in the image of God (or as the image of God, a rendering based on a point of Hebrew grammar and syntax that leads me to take the functional view of the image).12 The image of God describes a status, not any quality or attribute.13 In Gen 1:26-27 we have the word ʾādām with and without the definite article as the point of reference of the same act of creation, a creation that Genesis 5:1a assigns specifically to Adam the person. Then in Gen 5:3 we get the lifespan of ʾādām (again, without the article). The point is that in Gen 5:1-3 we see that the writer uses ʾādām without the article to refer to both the person Adam and the humanity that extends from him and Eve. Isolating that one textual form to non-Adamic humans cannot stand.14

Swamidass also notes appeals to Gen 6:1-4, the episode of the sons of God, the daughters of men, and the Nephilim. Some posit that the sons of God are the godly line of Adam, continued via Seth in Genesis 5, and the daughters of man are some other less godly human lineage (that of Cain in the standard articulation of this idea). The Nephilim produced by the forbidden union are not giants or anything else unusual, since (so this view argues) “Nephilim” comes from Hebrew naphal and means “fallen ones” (evil people) or “those who fall upon” (warriors).

I say Swamidass “notes” this perspective because he doesn’t base his hypothesis on this trajectory. This is wise, as none of these presumptions stand scrutiny. They have no textual, contextual, or logical merit.15 The passage rather describes a transgression of supernatural and natural realms and how it produced demigods and/or giants and, ultimately, demons.16 This interpretation is firmly rooted in the Mesopotamian literature against which the Gen 6:1-4 polemic is aimed and has clear relationships to Second Temple Jewish texts that also references the earlier Mesopotamian target, and which are repurposed by New Testament writers. The scholarly literature establishing these assertions is copious.17

Romans 5:12-14 a Fatal Blow?

This brings us to the passage that launched La Peyrère’s thinking in regard to pre-Adamites. La Peyrère was also influenced by other factors, such as his exposure to the monuments of Egypt and Babylon, their knowledge of astronomy (known to him through classical writers), and more recent discoveries of people in remote locations, but Romans 5:12-14 was where he himself said his journey began. The writings of contemporaries in his circle make it clear that La Peyrère could not read Greek (nor Hebrew for that matter), so this passage in Romans was known to him via Latin and a 1656 English translation that he quotes in his writings, which reads as follows:

As by one man sin entered into the world, and by sin, death: so likewise death had power over all men, because in him all men sinned. For till the time of the Law sin was in the world, but sin was not imputed, when the Law was not. But death reigned from Adam into Moses, even upon those who had not sinned according to the similitude of the transgression of Adam, who is The Type of the future.18

The key line for La Peyrère in this regard was “For till the time of the Law sin was in the world, but sin was not imputed, when the Law was not.” La Peyrère interpreted the passage to say that law came into the world with Adam (by which he meant “natural law” that preceded the Law of Moses). This must be the case since there was sin before Adam. How can one call any act “sin” if there was no law? The language must speak of willful acts against an order by intelligent, willful transgressors. Consequently, La Peyrère reasoned, “there was sin before Adam, but it only took on moral significance with Adam. Therefore, there must have been men before Adam.”19

Contemporary biblical scholars of all theological persuasions (or none) will immediately recognize the weaknesses of these arguments and La Peyrère’s interpretation. But that doesn’t matter. Swamidass isn’t depending on Romans 5. So, the question in regard to Romans 5:12-14 should be whether, if the Swamidass hypothesis is correct, there is a violation of the meaning of that text? In that regard, the central point is v. 12 (now from ESV):

12 Therefore, just as sin came into the world through one man, and death through sin, and so death spread to all men because all sinned—

The verse seems to disallow people before Adam. It clearly states that Adam’s sin brought death into God’s world. If there were people before Adam, did they not die? If these people could die, how are they really people? Could they not sin? In any view of the image, being created in God’s image has something to do with moral responsibility and culpability. This is especially true, though, for the functional view (which, again, I hold). Romans 5 seems to force the conclusion that humans created in God’s image before Adam cannot be biblically feasible.

But this conclusion is premature as the following thought experiment illustrates.

We know from elsewhere in Romans 5 that Paul is talking about Adam, and so he has the Fall of Genesis 3 in view, the first sin of humankind. There’s no ambiguity on that point. Romans 5:12’s statement that, “just as sin came into the world through one man,” is about the first sin, which can only refer to what happened in Eden to the man Adam (and Eve, by extension). It thus applies only to Adam, Eve, and their progeny—no one else. The ensuing phrase (“and death through sin”) has nothing to do with physical death of any animal or person before the Fall. It is a comment about the event of Eden and circumstances after the Fall. Death now invades the Edenic storyline which will affect all of Adam and Eve’s descendants. The original desire of God did not include death.

Another phrase follows: “so death spread to all men [i.e., humankind.” Death has entered the picture because of Adam and Eve’s sin. The death Paul is speaking of is both spiritual and physical. Spiritually, the humans born from the couple that shared God’s sacred space are now estranged from God. Why this must be part of our reading of Eden’s fall has long been noted by biblical scholars. Adam and Eve didn’t drop over dead when they sinned—but they were separated from God. Physically, Adam and Eve will now age and die. Their children—and in the Swamidass hypothesis, this subsumes all humanity that extends from them—are no longer destined for immortality. Death spreads to all humanity—the humanity this concerns is the same humanity referenced with respect to the sin: Adam and Eve and all who will inherit the creation mandate from them—their children.

The last part of Romans 5:12 is another concern for many (ESV: “because all sinned”). This has, for the most part, been understood as indicating Adam’s guilt now falls to all his descendants (not just death, which is actually what the verse says was transmitted), via either the seminal or headship understanding. But a minority of Christian thinkers takes a different position, that Rom 5:12 has nothing to do with the transference of guilt.20 I hold this view, which is based on two considerations: (1) not over-reading the passage to insert guilt into the verse alongside death, and (2) interpreting the grammar and syntax of preposition epi+ relative pronoun preceding the verb form differently, and understanding the verb as a gnomic (or perhaps a constative) aorist, so that the phrase is translated “with the result that all sin / have sinned.”21 Consequently, the idea traditionally extracted from Rom 5:12, that the guilt of Adam is somehow transferred to all humans thereafter isn’t an obstacle for me when considering the Swamidass hypothesis. However, it should be noted that his hypothesis isn’t dependent on this minority view of Rom 5:12. Why? Because he’s still only talking about humans who descend from Adam and Eve. The question of why humans are guilty before God is wrapped up in how one takes the end of Rom 5:12. Swamidass isn’t concerned with that issue.

What about the humans before Adam and Eve’s fall—the humans with which Rom 5:12 is not concerned. If they are human must they not also be created as God’s imagers? It is at this point that the functional view of the image of God (vs. a qualitative view) is brought to bear in my thought experiment. It matters not that hominid archaeology shows us they had human intelligence. Intelligence—indeed no quality at all—defines the image of God. Rather, the grammar informs us we should understand the image as a functional status.22 Adam, Eve, and their descendants (cf. Gen 5:1-3; 9:6) are the image of God. That is, they were created to be God’s proxies on earth, which explains why the image language is accompanied by a mandate in Gen 1:27-28). Attributes are the means by which this new, unique status will be carried out but, as noted earlier, all the attributes theologians tend to use to define the image are either not unique to Adam, Eve, and their descendants, or are not equally possessed by all their descendants. No quality or set of qualities defines the image. It is a functional status.

The practical result of this approach is that the everlasting destiny of creatures that have intelligence or some other capacity in a way that transcends the animal world are outside of both the act that makes redemption necessary and that secures redemption. They may be part of the new earth regardless. Animals certainly are (the new Eden is what the old Eden was supposed to be, only on a global scale). Colossians 1:20 is a significant text in this regard. Paul is not speaking of the offer of redemption in that passage. “Reconcil[ing] to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven” refers to the restoration of creation order and authority. With respect to the Swamidass hypothesis, humans outside Adam and Eve were part of the original creation, though outside it. Colossians 1:20 may therefore indicate that those humans will be part of the new creation as well. At the very least, Col 1:20 should be part of further discussion of the hypothesis.23

And so in the end of our thought experiment, the Swamidass hypothesis is workable. Romans 5:12 need not violate Genesis 1, 2, or 3. God created Adam and Eve de novo, stepping into his experiment to create a world filled with embodied life forms. He enjoyed it so much that he desired to intervene and take some of the material of that world to create people who would image (represent) him, to be steward-rulers of his property. They would be his children and partners.

References

Amar Annus, “On the Origin of the Watchers: A Comparative Study of the Antediluvian Wisdom in Mesopotamian and Jewish Traditions,” Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha 19.4 (2010): 277–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0951820710373978

Amar Annus, “Are There Greek Rephaim? On the Etymology of Greek Meropes and Titanes,” Ugarit Forschungen 31 (1999).

Jacques E. J. Boulet, “The Biblical Hebrew Beth Essentiae: Predicate Marker,” Journal for Semitics 29:2 (2020), 27 pp. (not numbered). https://doi.org/10.25159/2663-6573/8019

Jan N. Bremmer, “Greek Fallen Angels: Kronos and the Titans,” in Greek Religion and Culture, the Bible, and the Ancient Near East (Leiden: Brill, 2008). https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004164734.i-426.29

W. Randall Garr, In His Own Image and Likeness: Humanity, Divinity, and Monotheism (Culture and History of the Ancient Near East 15; Leiden: Brill, 2003).

George Wesley Buchanan, “The Old Testament Meaning of the Knowledge of Good and Evil,” Journal of Biblical Literature 75:2 (1956): 114-120. https://doi.org/10.2307/3261486

Umberto Cassuto, A Commentary on the Book of Genesis: Part I, From Adam to Noah (Genesis I–VI 8), trans. Israel Abrahams (Jerusalem: The Magnes Press, The Hebrew University, 1998).

C. E. B. Cranfield, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans, International Critical Commentary (London; New York: T&T Clark International, 2004).

Michael J. Crowe, The Extraterrestrial Life Debate: Antiquity to 1915: A Source Book (University of Notre Dame Press, 2008).

Ida Frölich, “Mesopotamian Elements and the Watchers Traditions,” in The Watchers in Jewish and Christian Traditions (ed. Angela Kim Hawkins, Kelley Coblentz Bautch, and John Endres; Minneapolis: Fortress, 2014).

Friedrich Wilhelm Gesenius, Gesenius’ Hebrew Grammar (Edited by E. Kautzsch and Sir Arthur Ernest Cowley; 2d English ed.; Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1910), 379 (Par. 119i).

Robert Gordis, “The Knowledge of Good and Evil in the Old Testament and the Qumran Scrolls,” Journal of Biblical Literature 76:2 (1957). https://doi.org/10.2307/3261283

Victor P. Hamilton, The Book of Genesis, Chapters 1–17, The New International Commentary on the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1990).

Murray J. Harris, Prepositions and Theology in the Greek New Testament: An Essential Reference Resource for Exegesis (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2012).

Adam Harwood, “The Spiritual Condition of Infants: A Biblical-Historical Survey and Systematic Proposal,” Diss. Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2007).

Michael S. Heiser, The Unseen Realm (Lexham Press, 2015).

Michael S. Heiser, Angels: What the Bible Really Says about God’s Heavenly Host (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2018).

David M. Johnson, “ Hesiod’s Descriptions of Tartarus (Theogony 721–819),” The Phoenix 53.1–2 (1999): 8–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/1088120

Paul Joüon and Takamitsu Muraoka, A Grammar of Biblical Hebrew (Rome: Pontificio Istituto Biblico, 2003), 2:486 (Par 133c).

Helge S. Kvanvig, Roots of Apocalyptic: The Mesopotamian Background of the Enoch Figure and the Son of Man (Wissenschaftliche Monographien zum Alten und Neuen Testament 61; Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 1988).

H. Kvanvig, _ Primeval History: Babylonian, Biblical, and Enochic_ (Supplements to the Journal for the Study of Judaism 149; Leiden: Brill, 2011).

David N. Livingstone, Adam’s Ancestors: Race, Religion, and the Politics of Human Origins (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011.

Andrew Louth, Introducing Eastern Orthodox Theology (London: SPCK, 2013).

G. Mussies, “Titans,” Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible.

G. Mussies, Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible.

Birger A. Pearson, “A Reminiscence of Classical Myth at 2 Peter 2.4,” Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 10 (1969): 71–80.

Isaac La Peyrère, Men before Adam, or a Discourse upon the twelfth, thirteenth and fourteenth Verses of the First Chapter of the Epistle of the Apostle Paul to the Romans. By which are prov’d that the first Men were created before Adam (London, 1656).

Isaac La Peyrère, Systema Theologicum ex Præadamitarum Hypothesi: Pars prima, lib. ii, cap. xi, 1655.

Richard H. Popkin, Isaac La Peyrère (1596-1676): His Life, Work, and Influence (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1987).

Henri Rondet, Original Sin: The Patristic and Theological Background (transl. Cajetan Finegan; New York: Alba House, 1972).

Seth D. Postell, Adam as Israel: Genesis 1-3 as the Introduction to the Torah and Tanakh (Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2011).

Steven E. Runge, Discourse Grammar of the Greek New Testament: A Practical Introduction for Teaching and Exegesis (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2010).

Herold S. Stern, “The Knowledge of Good and Evil,” Vetus Testamentum 8:1 (1958).

Loren T. Stuckenbruck, “Giant Mythology and Demonology: From Ancient Near East to the Dead Sea Scrolls,” in Demons: The Demonology of Israelite-Jewish and Early Christian Literature in Context of Their Environment, ed. Armin Lange, Hermann Lichtenberger, and Diethard Römheld (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2003).

Loren T. Stuckenbruck, “The ‘Angels’ and ‘Giants’ of Genesis 6:1–4 in Second and Third Century BCE Jewish Interpretation: Reflections on the Posture of Early Apocalyptic Traditions,” DSD 7.3 (2000).

S. Joshua Swamidass, The Genealogical Adam and Eve: The Surprising Science of Universal Ancestry (InterVarsity Press, 2019).

Earl Waggoner, “Baptist Approaches to the Question of Infant Salvation,” Diss. New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary, 1999).

Daniel B. Wallace, Greek Grammar Beyond the Basics - Exegetical Syntax of the New Testament (Zondervan Publishing House and Galaxie Software, 1996).

David M. Weaver, “The exegesis of Romans 5:12 among the Greek fathers and its implication for the doctrine of original sin,” Diss. St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary, 1983).

Claus Westermann, _ Genesis 1–11: A Continental Commentary_ (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1994).

Archie T. Wright, The Origin of Evil Spirits: The Reception of Genesis 6:1–4 in Early Jewish Literature (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2013).

Archie T. Wright, “Some Observations on Philo’s De Gigantibus and Evil Spirits in Second Temple Judaism,” Journal for the Study of Judaism 36.4 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1163/157006305774482678

Jan 4, 2022

Dec 1, 2020

Jun 30, 2025