In order to preserve the academic and historical record, this deleted article is published under Fair Use. All editorial comments are marked with a light gray background.

The article was first published by the BioLogos Foundation in 2015.

In 2017, this article was found to have several conclusion-altering scientific errors. January 2020, BioLogos briefly acknowledged errors in their work. However, they declined our request to transparently correct the scientific errors in this article. Instead, in June 2021, BioLogos deleted this article and several others.

William Lane Craig, the Historical Adam, and Monogenesis

Previously, we have looked at the arguments of Vern Poythress as they pertain to human common ancestry, population genetics, and locating Adam and Eve in human prehistory. A second well-known apologist who has also interacted with these data is Dr. William Lane Craig. Like Poythress, Craig is an Old-Earth, progressive creationist who holds to the view that all humans descend uniquely from Adam and Eve—though Craig is more open than Poythress to the possibility of humans sharing ancestry with other forms of life. To his credit, Craig is aware that he is not an expert in this area, and often assumes a humble posture when discussing these matters:

So some sort of a progressive creationist view, I think, would explain the evidence quite well. It would allow you to affirm or deny if you wish the thesis of common ancestry and it would supplement the mechanisms of genetic mutation and natural selection with divine intervention. I find some sort of progressive creationism to be an attractive view.

Again, I want to reiterate that on these issues I am like many of you a scientific layperson. I am someone who has an interest in these subjects, I want to learn and to study them further, and explore them more deeply. So these opinions are held tentatively and lightly and are subject to revision.

I have had the opportunity to meet Dr. Craig in person, and found him to be thoughtful, congenial and interested in learning more about how modern genetics plays into the conversation about the historical Adam and Eve. While Craig has learned about— and has correctly understood the impact of—the genetic evidence for human common ancestry, his understanding of the evidence from human population genetics is lacking in certain respects. These misunderstandings, unfortunately, lead him to make some basic errors. As he sees it, holding to a historical Adam—in the sense that all humans descend uniquely from an original ancestral couple—remains defensible, since the conclusions of human population genetics are based on assumptions open to critique:

[Geneticists] look at the amount of variability in the genetic structure and then you calculate how this could have arisen based upon mutation rates and the amount of time available. That will then give you these population estimates. But there are quite a number of assumptions that go into this kind of modeling that the defender of the historical Adam, I think, could challenge.

Craig’s defense of a historic Adam and human descent from an ancestral pair (i.e. genetic monogenesis) thus rests on the idea that there is reasonable uncertainty in population genetics measures:

What we need to understand is that these are genetic estimates based upon mathematical modeling and projections into the past. We know that that kind of mathematical modeling is based upon certain assumptions that may or may not be true, and can sometimes be wildly incorrect in their projections… It could well be the case that these mathematical models are simply incorrect.

Moreover, Craig advances the opinion that this uncertainty is great enough to allow one to hold to genetic monogenesis:

When you think about it, it is really quite remarkable, it seems to me, that with these models they are able to get the minimum human population size down to a couple thousand people. I mean, that in itself is astonishing. It wouldn’t take a great error to go from two thousand to two, I think.

So, what “assumptions” does Craig have in mind? Two major themes in Craig’s interaction with population genetics evidence are (a) that population geneticists assume a constant mutation rate for the human lineage, and that (b) population genetics models have been shown to overestimate real populations whose actual demographics are known. We will deal with these issues in turn.

Accelerated mutation rates?

Craig posits that mutation rates may not have been constant over human history, and that in the past mutation rates may have been much higher. Such accelerated rates, he argues, could indeed produce the genetic diversity we see in the present day starting from only two people:

The problem is the population size. In order to get this amount of genetic diversity, the claim is you needed to have at least 2,000 people originally to result in this. One of the assumptions that is based upon is that the rate of mutation doesn’t change. But if the mutation rates are changing then they could accelerate and that could produce greater diversity than one might expect. You might say that increasing diversity would have a selective advantage so this perhaps would be a kind of accelerating process. Again, we just don’t know that these mutation rates have been constant over all of these thousands of years.

There are, of course, several problems with this line of argument (not least that genetics indicates that we descend from a population of about 10,000, not 2,000). First, it is an ad hoc line of argumentation—the argument is made only because the evidence does not fit with Craig’s prior expectation that we all descend from an ancestral couple. Second, there is indeed good evidence that the mutation rate our lineage experienced has not changed appreciably in the last several million years.

There are several independent ways to estimate human mutation rates. An excellent overview of the various methods can be found at this series of blog posts by Larry Moran, a biochemist at the University of Toronto: the biochemical method; the phylogenetic method, and the direct method. For our question at hand, the phylogenetic method is of particular interest: it estimates the mutation rate on the human lineage since our separation from chimpanzees. In brief, we can compare the differences we see in the present-day human genome, the present-day chimpanzee genome, and using reasonable estimates of generation times, infer the number of mutations per generation in our lineage, as well as in the lineage leading to chimpanzees, with both lineages descending from a common ancestral population. This estimate is an average for our lineage over the last several million years—and it agrees well with the estimates we see using the biochemical and direct methods. Even the best-case scenario for Craig—that no mutations occurred at all in the lineage leading to chimpanzees, and every difference between the genomes of our two species resulted from mutations in the human lineage only—does not provide a mutation rate high enough to account for the diversity we see in present-day humans assuming they descend from an original pair.

Finally, only some techniques used to measure human population dynamics over time employ estimates of mutation rates. Other methods—which do not use estimates of mutation rates—return the same results as mutation rate-based methods. One such example is one we have discussed: estimating human population size over time using linkage disequilibrium. Craig’s argument thus needs to explain why these methods agree with mutation-based methods, since speculating about mutation rates does not affect these measurements. Craig also needs to address why the various independent methods used to measure the population size of our lineage agree with one another: if indeed we all descend uniquely from an ancestral pair, why is it that these independent methods all return the same values? The reasonable conclusion is that these methods are telling us something valid about our evolutionary history. These methods and their conclusions are subject to revision and refinement, of course—but unlike Craig hopes for, it is not reasonable to expect that that refinement will reduce our ancestry from 10,000 to two.

The Historical Adam and Human Inheritance Patterns

So far, we began to explore the ideas of apologist William Lane Craig as they pertain to Adam and Eve. Specifically, we saw that Craig holds to genetic monogenesis—the hypothesis that humans descend uniquely from an ancestral couple, rather than a population—in the face of population genetics evidence to the contrary. Part of his reasoning, as we saw, was to suggest that the human mutation rate was once far higher than it is now. For Craig, this includes the possibility that God may have supernaturally increased the mutation rate of the human lineage to account for present-day genetic diversity. With such a miraculously accelerated rate, Craig argues, the genetic diversity we see in present-day humans could in fact arise from just two individuals— the historical Adam and Eve:

In order to calculate whether this amount of genetic diversity could arise from an initial human pair, you have to assume a certain mutation rate that is constant over time. One might deny this conclusion by postulating accelerated rates of mutation in the early human population. One could see this as a result of divine intervention—that God accelerated the evolution of early humans so as to produce greater genetic diversity.

As we have seen, this argument fails to account for calculations of human ancestral population sizes that are not dependent on estimates of mutation rate. An additional problem with this argument is that humans are not merely genetically diverse, but that we observe patterns of diversity in different human populations. Genetic variation in humans is not uniformly distributed across the globe. If you examine Northern European populations, for example, you find certain genetic variants connected to other certain variants in predictable ways. The same holds for any other human population— Han Chinese, populations in sub-Saharan Africa, and so on. It is these patterns of variants linked on chromosome sections that allow us to use linkage disequilibrium to estimate our ancestral population size. And as we have seen, this method returns the same value (~10,000) that other methods do.

The question for Craig, then, is not merely “why are humans so genetically diverse?” but rather “why do humans have their abundant genetic diversity in the particular pattern we observe in the present day? ”While the first question might appear to have a simple answer, however farfetched it may be—i.e. increased mutation rates—this answer does not even begin to explain the second question. Mere mutation alone would not put certain combinations of variants into various populations. These patterns are inheritance patterns, not mutation patterns.

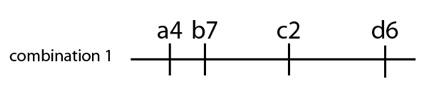

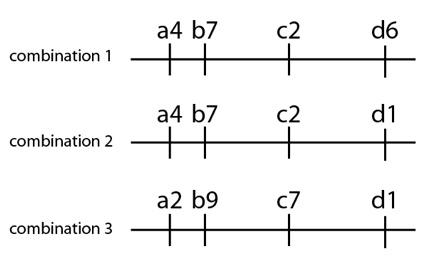

Let’s look at an example to help us understand this issue. Suppose one small segment of a human chromosome has four regions where variation is present in human populations. We can represent the chromosome as a line, and mark off the four locations with letters (a, b, c and d). Each of these locations has multiple DNA sequence variants within the population. Suppose for one individual, they have the following combination on one of their chromosomes: they have DNA variant 4 at position “a”, variant 7 at position “b” and so on:

Now suppose we look at other individuals from the same population for these same four chromosome locations. In them we observe new DNA variations present at locations “c” and “d”, and we observe different combinations of those variants:

At locations “c” and “d”, we see two options at each location, and we see a few combinations: (c2 with d6), (c2 with d1), and (c7 with d1). Now the question for the geneticist arises: how did these three possible combinations arise? The basic issue is this: are we looking at the results of multiple, independent mutation events, or mixing and matching of the same mutations into various combinations through genetic recombination? Take for example variant c2: we see this exact variant (down to the precise mutation at the DNA level) in the top two chromosome combinations. The probability that these two chromosomes independently mutated to variant c2 is possible, but tiny. Far, far likelier is that these two chromosomes have the same c2, from a single mutation event in the past that has been recombined into two combinations with different variants at the d location. For example, suppose this population has many individuals with the (c2 d6) combination (first chromosome), but fewer individuals with the (c2 d1) combination (second chromosome). This observation suggests that the (c2 d6) combination is older, and has been passed down from a distant ancestor to more offspring over time. The rarer (c2 d1) combination is likely more recent, and it likely arose by a recombination event. Suppose the third combination (a2 b9 c7 d1) is also common in the population—this is the likely source of the d1 variant seen in the second chromosome combination. The alternative hypothesis is that the d1 variant arose independently twice (or that the c2 variant did)—i.e. the exact same mutation happened twice over. This is much less likely than assembling the second chromosome through the mixing and matching of recombination using the common first and third combinations.

And here’s the rub: the recombination events are also infrequent events. The more closely linked together two locations on a chromosome are, the less frequent recombination becomes. We can directly measure recombination rates in present-day humans and other organisms, and we have a good understanding of how physical separation of two locations on a chromosome is proportional to the recombination frequency between them.

So, not only do we need to account for rare mutation events, we also need to account for rare recombination events—in this case, the breakage and rejoining of chromosomes through the biological process called “ crossing over”. While this example uses only four locations, imagine chromosomes that have hundreds or thousands of locations with these sorts of patterns—which is what we see in present-day humans. There are, after all, about 300,000 locations in our genome of 3 billion DNA base pairs that have this sort of variation present, in a staggering array of combinations. That amount of diversity requires a large ancestral population, because it is too improbable to postulate that a huge number of rare recombination events occurred in a small number of ancestors. That number of rare events requires a large population for the probabilities to be reasonable—just as the number of DNA variants we see in present-day humans requires a large ancestral population to allow for rare mutation events to occur.

So, an accelerated mutation rate alone is simply not going to account for those patterns. A normal mutation rate followed by genetic recombination of mutations over time in a large ancestral population, however, easily explains the pattern.

To what end, variation?

I suppose that Craig might reply that we could expect miraculous governance of recombination as well as miraculous acceleration of mutation to maintain the view, in spite of the evidence, that humans uniquely descend from an ancestral couple rather than a population. The question I have, aside from the ad hoc nature of such arguments, is why? Why would God engineer this variation into human populations in such a way to appear to be a result entirely consistent with processes and rates we observe in the present, when there is no functional reason for this variation? After all, we are discussing variation in present-day humans, which means that none of the variation we are discussing contributes to our being human. Humans could be absolutely uniform for these locations in our genome with no virtually impact on our biology, except in rare instances. This is variation that we don’t need or use—so the suggestion that God engineered it into present-day human populations, giving the strong impression with multiple, converging lines of evidence that we are a species descended from a large population, but for no apparent purpose, is frankly baffling.

The Kerguelen Mouflon Sheep

One claim made by Craig that we have not yet addressed in detail is this: that population genetics models have been shown to significantly overestimate the ancestral sizes of real populations where their real genetic history is known. The main example that Craig proffers in support of this claim concerns a scientific study examining a population of invasive sheep on a remote island in the southern Indian Ocean.

It’s little wonder that this study caught the attention of those wanting to hold to humanity descending uniquely from a single ancestral couple. In the 1950s, a population of domestic mouflon sheep was founded on Haute Island in the Kerguelen archipelago with a single ram and a single ewe, both introduced as lambs. The extreme remoteness of the Kerguelen archipelago (over 3000 kilometers to the next inhabited island!), coupled with the continuous monitoring the islands have had by French scientists, ensures that no other sheep have been introduced since the population was founded. As such, this population genuinely has the sheep equivalent of a genetic “Adam and Eve” in the sense that Craig maintains for humanity. Even more exciting, though, was the finding that the sheep on this island have higher levels of heterozygosity—which we will discuss in detail later but for now can think of as one measure of “genetic diversity”—than a certain mathematical model predicts. For an apologetics-minded approach, it seems tailor-made: population genetics models overestimate the heterozygosity of a population known to be founded by only two individuals—and thus measurements of human population sizes might similarly be overestimates, and we can hold on to a literal Adam and Eve who were our sole genetic progenitors! This basic argument first appears in the Christian anti-evolutionary literature in 2010, in the work of Reasons to Believe (RTB). Since then, it has appeared in numerous places online, though Craig is basing his argument primarily on RTB sources. As we will see, his argument is not a valid one. It is based on a significant misunderstanding of the study in question, and population genetics in general—but it will take some effort to explain why this is so.

Based on this study, Craig makes the following four claims:

- The study shows that the Kerguelen sheep have higher heterozygosity than expected, and show an increase in heterozygosity over time.

This claim is true, but Craig misunderstands why it is true, as his second claim shows:

- The observed increase in heterozygosity is attributable to an increased mutation rate driven by natural selection.

This (erroneous) claim is repeated several times as Craig discusses this study. Some examples include:

So natural selection actually accelerates the rise of genetic diversity because it has survival value in the struggle for survival.

In other words, had they not known that there were originally only two sheep placed on that island, looking at the genetic diversity exhibited by the present sheep using the mathematical models they would have over estimated the minimal size that that population would have had at any time in the past because the models did not take account of the accelerated rates of genetic mutation that were driven by natural selection.

This claim is simply false: natural selection does not, and cannot, increase the rate of mutation, however beneficial an increase in mutation frequency might be. Natural selection acts only on genetic variation that already exists in a population. Craig has confused an increase in heterozygosity over time with an increase in mutation rate over time. In fact, as we will see, an increase in heterozygosity over time does not require any new mutations at all.

Natural selection therefore may have driven an increased mutation rate in the human lineage, and an appeal to divine intervention for increasing human genetic diversity may not be necessary.

If so, then population genetics models may underestimate human ancestral population sizes because they fail to account for natural selection. If so, then the “traditional view” that we descend uniquely from an ancestral couple remains defensible.

You might recall that Craig has been attempting to argue for an increased mutation rate in the human lineage in order to explain how humans are so genetically diverse today (leaving aside our discussion that a mere increase in mutation rate is not adequate to explain the pattern of variation we observe in humans). He clearly has this issue in mind when invoking the mouflon study:

If it is the case that natural selection can drive the increase in genetic diversity then that calls into question the assumption that the mutation rates have been constant over time for humanity, and hence it calls into question the population estimates based on that assumption.

The Kerguelen sheep study thus does double duty for Craig: it offers, in his mind, a natural explanation for increased mutation rates, and simultaneously throws human population genetics models into doubt. Since alternative views that accept that humans descending from a population raise theological challenges for him, he sees this evidence as reason not to be “forced” to accept such a view:

…I am just saying that realize that all of these alternatives have really interesting and unsettling theological reverberations that we need to be aware of. So that is an alternative that some people have suggested. What I am arguing right now is I am not sure we are forced to that alternative because I am not convinced that the evidence is inconsistent with there being an original historical human pair. The bottleneck got so small that it was just two people—Adam and Eve—and if you then imagine accelerated rates of mutation which would be either by divine intervention or just naturally, like the sheep on Haute Island, then that is entirely consistent with the evidence that we have today.

In order to understand why Craig is mistaken, we will have to understand exactly what heterozygosity is, how it relates to genetic diversity, and how natural selection has shaped it over time in the Kerguelen mouflon population. Next, we will start with these key issues.

An Introduction to “Heterozygosity”

In the last section, we began to examine William Lane Craig’s arguments based on a study of a population of mouflon sheep founded by a single breeding pair. As we saw, Craig’s use of this study was twofold: to claim it as an example of natural selection increasing mutation rates (and thus provide a supposed natural explanation for accelerated mutation rates in the human lineage), as well as an example of population genetics models overestimating a known ancestral population size (since the study found the sheep population to have greater levels of heterozygosity than expected by one mathematical model). Since understanding why Craig is mistaken for both counts requires a working knowledge of what exactly “heterozygosity” is, let’s tackle this issue first.

Non-biologists are usually most familiar with organisms that have two copies of their genetic material—so-called “diploid” organisms. Humans, for example, receive two sets of chromosomes at conception—one set from mom (22 regular chromosomes plus an X chromosome), and one set from dad (22 regular chromosomes plus either an X or Y chromosome). Combined, this is what gives us our standard 46 chromosome set. What this means is that for every location (or, to use the correct genetic term, locus) in our genome, there are two copies present. For any given locus, then, the two copies may have the exact same sequence, or they may have slightly different sequences due to genetic variation in the population. Different sequences are called different alleles. In genetic-speak, then, diploid organisms can have two different alleles at any given locus—or both alleles at a locus may be the same. If an organism has two different alleles at a locus, they are said to be heterozygous at that locus. Conversely, if an organism has two identical alleles at a locus, they are said to be homozygous at that locus.

Geneticists often use uppercase and lowercase letters as symbols for different alleles at a locus. If you remember Gregor Mendel and his pea plants from your high school biology class, you were introduced to this system. For example, at the “aye” locus, we can designate two alleles: “A” and “a”. At the DNA level, these two alleles have some sort of sequence difference, though its exact nature isn’t important for this example. What is important, however, is understanding that these two alleles give us three possible genetic combinations for this locus:

- Homozygous for “A” or the AA “genotype” (note: “genotype” simply means “combination of alleles at a locus”),

- Heterozygous, i.e. the Aa genotype, or aA,

- Homozygous for “a”, or the aa genotype.

If we now consider a population of organisms, we can determine what proportion of them are heterozygous at the “aye” locus. For example, suppose a small population of 100 individuals has the following number of each genotype:

- 25 are AA

- 50 are Aa

- 25 are aa

In this case, there are 50/100 individuals that are heterozygous, so the heterozygosity of this population at the “aye” locus is ½, or 0.5.

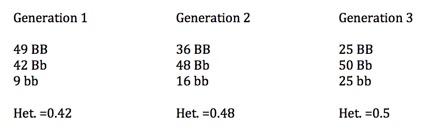

Now, consider how this measure might change over time. In a small population such as this one, chance effects alone might mean that one allele could become more common over time, and the other allele less common. For example, suppose we revisit the same population above several generations later, and find the following:

- 64 are AA

- 32 are Aa

- 4 are aa

In this population the heterozygosity at the “aye” locus is now 32/100, or 0.32—a decrease from the prior measurement several generations before. What has happened is that the “a” allele has become less common, and accordingly the Aa genotype is now also less common as a result. In small populations, this sort of thing happens readily by chance, simply because each generation may not exactly reflect the allele frequencies of the prior generation. In a small population, the effects of chance can have a large effect on the population as a whole. As an example, imagine an animal population of 10 individuals that has 6 AA individuals, 3 Aa individuals, and only 1 aa individual: if something happened by chance to the aa individual (it dies in a rock slide before breeding, for instance) this event would have a large impact on the frequency of the “a” allele. In a population of 1000 individuals with the same starting proportions (600 AA, 300 Aa, 100 aa) losing one aa individual by chance would hardly have an effect at all. This is called “genetic drift”—a change in allele frequencies due to stochastic events.

In fact, the decrease in heterozygosity over time is expected to be proportional to the size of the population: smaller populations lose heterozygosity more quickly than do larger populations, due to these sort of chance sampling events. The reason for this is simple: in small populations, losing alleles is easy due to chance events, but gaining alleles over time, through mutation, takes far, far longer because new mutations are so rare. For example, our hypothetical population of 10 individuals (6 AA individuals, 3 Aa individuals, 1 aa individual) could, over time, lose the “a” allele altogether by chance. This population would then have only the “A” allele (i.e. all individuals would have the AA genotype). In order for heterozygosity to increase at this locus, we would need to wait for a mutation to convert one of these “A” alleles to a new “a” allele—and we would wait a very long time. The net result is that over time, we expect small populations to lose heterozygosity. Genetic diversity is easy to lose, and hard to gain in a small population.

It was this effect that the research group was interested in when studying the isolated mouflon sheep population. The basic prediction was that for this population, heterozygosity would decrease over time since the population size was small. (Studying these processes are important for understanding how other small populations change over time, primarily endangered species with reduced genetic diversity.)

What the research group found, however, was that heterozygosity in this population had increased over their sampling period, and at more than one locus (the study used preserved samples of animals taken from the population at different times to measure heterozygosity at different time points spanning several decades). Why then, was this population not showing a steady decline in heterozygosity over time?

One likely reason is the one the authors of the study suggest: natural selection. The equations that predict the loss of heterozygosity over time do so with the assumption that the alleles in question are not under selection. But if the heterozygous combination of alleles provides a reproductive advantage, then an increase in heterozygosity would not be surprising at all in a small population. Let’s consider a second locus, the “bee” locus. If the Bb genotype has an advantage over the BB or bb genotypes, then this locus is less likely to lose heterozygosity over time, because more Bb individuals, on average, will reproduce successfully than will the BB or bb individuals. This means that neither the “B” nor “b” alleles will become rare in the population, since the most successful genotype has both alleles in it.

So, over time we might see something like the following in a population:

What is important to notice here is that while natural selection can increase the heterozygosity of a population over time, it does not involve new alleles caused by mutation. It merely involves an allele that already exists in the population becoming more common over time, such that the population has more heterozygous individuals than it did before.

With this understanding, it is easy to see just how off base Craig’s first argument is: that the mouflon sheep study somehow provides an example of natural selection increasing mutation rates. What the sheep study shows—unsurprisingly to geneticists—is that natural selection can preserve and even increase heterozygosity in a population over time, and that mutation has nothing to do with the process.

That Craig would advance such an argument reveals he misunderstands a very basic concept in population genetics, alas—as do his sources. This means that Craig’s argument for a “natural” mechanism to explain accelerated mutation rates in the human lineage has no support. While Craig could presumably fall back on divine intervention to explain human genetic diversity, we have already discussed why that is both an ad hoc and unsatisfying approach that does not withstand close scrutiny.

Heterozygosity, Continued

In the last few sections, we have been examining William Lane Craig’s arguments based on a study of a population of mouflon sheep founded by a single breeding pair. Craig uses this study in two ways, both of which are intended to cast doubt on the conclusion that humans descend from a population rather than uniquely from an ancestral couple. First, as we have already discussed, Craig mistakenly argues that an increase in heterozygosity over time in the mouflon sheep population is evidence that natural selection can increase mutation rates. (As we saw, it is rather the case that due to natural selection over time more sheep in the population became heterozygous for previously existing alleles—not that mutation produced new alleles). Secondly, Craig cites this study as an example of a population where population genetics models overestimate a known ancestral population size. This last point understandably has significant rhetorical impact: If population genetics models can overestimate the population size of a population we know was founded by only two sheep, then it naturally follows that population genetics models may similarly be overestimating the ancestral human population size as well. The importance of this point for Craig’s apologetic that humanity descends uniquely from an ancestral pair is evident in the following exchange between Craig and a questioner—a questioner who wonders if the mouflon sheep study causes scientists to accept the idea that humans may in fact descend from two individuals rather than a population:

Question: … when they did the sheep on the island, does the scientific community embrace that as an indication that perhaps there were a pair rather than a population?

Craig: I don’t know the answer to that. As I said, this is an area in which I have only a surface knowledge. So I am sharing with you some of this information to just give you a familiarity with the issue. But you can bet that obviously evolutionary biologists who study population genetics will not be persuaded by the example of the sheep on Haute Island.

Follow-up: Because they don’t want to be.

Craig: What I think we can say is that given this data the traditional view is defensible. But I am not suggesting that this proves it. It is just that we are looking here as to whether it is defensible in light of the data.

Craig, then, feels that this study gives scientific warrant to defend the idea that humans descend uniquely from Adam and Eve.

Summarizing the argument

Craig’s argument (which is based on the work of Reasons to Believe is relatively simple to understand:

- A population genetics model applied to the mouflon sheep population overestimates the known ancestral population size by up to a factor of 4.

- Population genetics models may similarly overestimate the ancestral population size of the human population.

- As such, the position that humans descend uniquely from an ancestral couple remains scientifically tenable.

The problems with this argument, however, are not readily apparent to a non-specialist. While it will take some effort to understand the details, here are summaries of the main problems with Craig’s line of argument, which we will explore in more detail in turn:

The “population genetics model” applied to this population is in fact nothing more than using a measure of heterozygosity—how many alleles are present for a few selected DNA sequences. However, Craig embraces the notion that natural selection is acting in the mouflon population, because he (erroneously) thinks it provides a mechanism for increasing mutation rate, as we have discussed. The action of selection, however, means that estimating population size using heterozygosity—as this study does—will return an inflated value, as the authors of the study rightly point out. Using heterozygosity to estimate population sizes in this way only works if the alleles being studied are not under selection. For Craig to argue that selection is acting means that he should expect the population size value to be inflated. That he argues both for selection and that the model is unreliable for this population is a non-sequitur: if selection is acting, then the model is working exactly as it should.

Human population genetics is much, much more advanced than this limited study, since it relies on numerous ways of estimating population sizes (rather than merely heterozygosity) and draws on the full genome sequence of thousands of humans. In contrast, the sheep study looks at only a handful of sequences in a small number of sheep.

Even if human population genetics was similarly limited to a simple estimate based on heterozygosity of a few genome locations (which it is most certainly not), the resulting estimate would range in the thousands, not close to 2 as Craig requires for his argument.

Having summarized the problems with Craig’s argument, let’s take a closer look at each.

Using heterozygosity to estimate population size, and its limits

You may recall that we previously discussed the concept of heterozygosity using letters to represent alleles (you may wish to re-read that section if you need a quick refresher). In this example, the population had two alleles of the “aye” locus, represented as “A” and “a”. Individuals in this population could either be homozygous for either allele (i.e. either “AA” or “aa”) or heterozygous (Aa). The proportion of individuals in the population that are heterozygous gives us the heterozygosity value for that locus. If all members of the population are Aa, the heterozygosity is 1; if one quarter are heterozygous the heterozygosity is 0.25, and so on.

A few factors can the change the heterozygosity value for a given locus in a population over time. New mutations can increase heterozygosity by adding new alleles to a population– though over the short timeframe that the mouflon population has been isolated it is not at all likely that heterozygosity has increased through mutation, since the probability of new alleles arising through mutation in only a few generations is very small. Selection for the Aa combination—i.e. if the Aa combination has a reproductive advantage—would also increase heterozygosity, and this sort of effect seems to have been occurring in this population. If a locus is not under selection, however, it is expected that its heterozygosity will decrease over time. The reason for this is straightforward: alleles can be lost by chance in a small population much more easily than they can be gained by (rare) mutation events. In the absence of selection there is nothing to stop this loss—known as “genetic drift”—from happening over time. With the knowledge of this effect, then, it is possible to obtain a rough estimate of a past population size by measuring the present-day heterozygosity. If heterozygosity declines at a certain rate over time due to chance, and we can measure present-day heterozygosity, we can infer how much heterozygosity was present in the past, and use that value to estimate a population size.

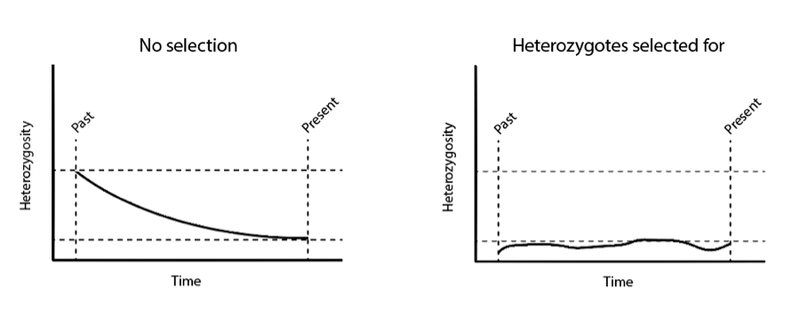

If selection is acting, however, this way of estimating population size simply will not work. For example, if the Aa combination is reproducing at a greater rate than the other two possibilities (AA or aa) then neither the “A” allele nor the “a” allele will be lost from the population over time by chance, since both alleles are being selected for in Aa individuals. In this case, we would expect heterozygosity to be stably preserved in the population over time, since neither allele will be lost due to chance. If we naively tried to calculate a prior population size without recognizing the effects of selection, we would be assuming that present-day heterozygosity was the left-over remnants of once greater levels that had been dropping over time due to genetic drift, and thus overestimate the ancestral size of the population. Compare the following two graphs: on the left, heterozygosity drops over time without selection. On the right, heterozygotes are selected for, resulting in relatively stable heterozygosity over time:

If we were to calculate the expected level of heterozygosity at a certain time in the past, assuming no selection when in fact selection was at work, we would overestimate it—and thus overestimate the size of the population at that time.

Of course, the question remains why the effects of selection are so pronounced in this sheep population, and more importantly, why we can be confident that similar effects are not at play in human populations.

Why the Mouflon Sheep are Different from Adam and Eve

So far, we examined Craig’s argument that the mouflon sheep study—a study that traces a population of sheep descended from a single breeding pair—lends scientific credence to his assertion that humans also descend uniquely from a pair (rather than from a population of about 10,000 individuals, which is the current scientific consensus). As we have seen, Craig failed to recognize that the effects of selection can maintain genetic diversity (in the form of heterozygosity) in a population—and that this is not a failure of population genetics models, but rather an expected consequence of selection.

So, why is it that selection has worked to maintain heterozygosity across large regions of the genome in this population of sheep? And how can we be sure that similar effects are not similarly confounding our estimates of ancestral human population sizes? To address these questions, we’ll need to learn a bit about how heredity works in small populations over short timescales.

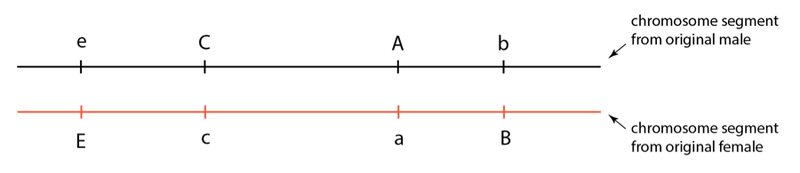

In a population founded by a single breeding pair, all progeny in the first generation will, of course, receive half of their chromosomes from this one male and half from the one female. Genetic differences between the original pair—i.e. different alleles that they carry on their chromosomes—will thus be inherited on these chromosomes. If we were to examine one genome region in one of the first generation progeny, we might see something like the following:

In this region, we see four locations where there are differences between the chromosomes inherited from the male and female. These allele differences can be represented with letters, as we have discussed. In this example, this sheep would be heterozygous at four locations in this region.

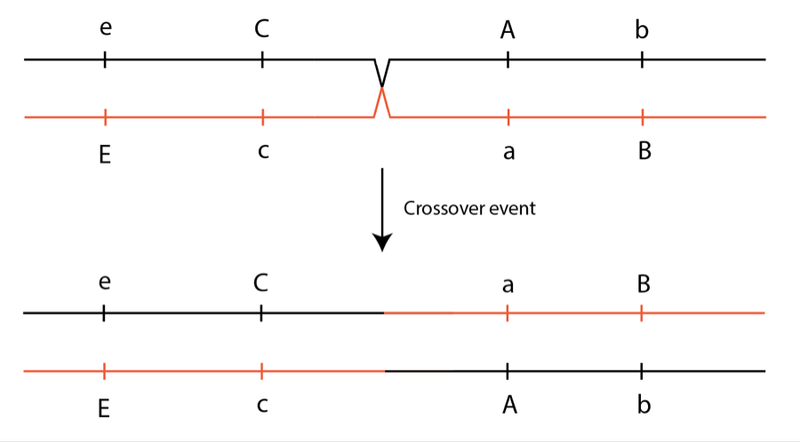

Now imagine that this sheep reaches breeding age and passes on its chromosomes. It would pass on these same groupings of alleles, unless there was mixing and matching of alleles through recombination (which you might recall as “crossing over” from high school biology). Crossing over may occur during the cell divisions that produce eggs and sperm, giving rise to new combinations of alleles:

While crossover events between any two genome locations are possible, in practice it can take many, many generations before two locations close together are recombined. What this means is that combinations of alleles will stay together in groups for long periods of time. In a population founded by only two individuals, the original allele groups from the founding parents will be broken up slowly over tens of generations through crossover events.

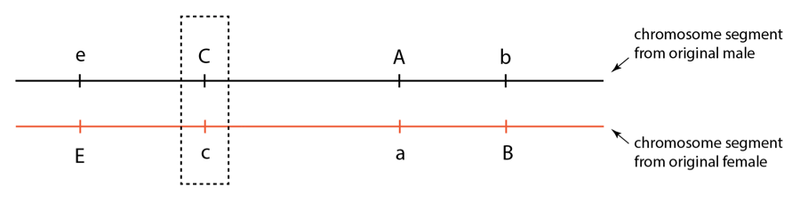

So, how does this affect influence selection and heterozygosity? It means that any location that is under selection will have a large genome region around it that will tag along for the ride, as it were. Let’s look at an example to illustrate this effect. Let’s return to the original combinations present in the first generation, but now consider what will occur if one location in this region is under selection to be heterozygous:

Suppose the “cee” location is under selection for heterozygosity. What this means is that animals that have both the “C” and “c” alleles will leave more progeny in the next generation than animals that are “CC” or “cc” (i.e. homozygous). In the absence of crossing over, however—and remember, crossing over in any given location is an infrequent event—selection for a “Cc” animal will at the same time select for animals that are heterozygous at the other three nearby locations. In this way, these other locations are also selected for heterozygosity, even though the real selection is acting only at the “cee” location. The other locations are merely “hitchhiking” because they are physically connected to the alleles under selection.

In a small population over a short timeframe (tens of generations) this effect can be quite pronounced. All it takes is a few locations in the genome to be under selection for heterozygosity, and large swaths of the genome will hitchhike along. This means that a large part of the genome will not act as though it is selectively neutral, even if the alleles themselves are neutral. For example, it may well be that the alleles at the “aye” location are neutral, meaning that the AA, Aa and aa combinations are all equally likely to leave progeny in the next generation. Based on this alone, there would be no disadvantage to this population to lose either the “A” allele or the “a” allele, with the resulting loss of heterozygosity. Moreover, should either allele be lost, it is lost for good—or at least until a mutation event re-creates it, something far too rare to be expected over a small number of generations. In our example, however, selection at the “cee” location also selects for heterozygosity at “aye”—and actively maintains both alleles at this location in the population over time. So, this is what is going on in the mouflon population—and this is why the authors find heterozygosity that exceeds the level expected from the loss of alleles not under selection. None of this is particularly surprising, of course, and is plainly laid out in the original research article. In the presence of selection, we expect this effect to occur.

Despite the confounding effects of selection, the effects on estimating the mouflon population size are not overly significant. The known ancestral population size is two; even taking the data at face value (assuming no selection) only raises the estimate to a maximum of eight individuals. For Craig to argue that this result somehow casts doubt on human studies is a flawed argument, for several reasons. First and foremost, ancestral human population size estimates are derived from many independent measures, not merely measures of heterozygosity, which is a rather simplistic measure. Secondly, we have full genome sequence data for tens of thousands of humans, and from this data we can directly observe that the short-term “hitchhiking” effects confounding the Mouflon study are not similarly confounding human studies. Thirdly, even if the confounding effects in the Mouflon study were somehow directly proportional to human studies (which for the foregoing reasons they are most certainly not), the end result would be an ancestral human population size of about 2500, not 2 as Craig requires.

So, the sheep study—though understandably tempting for apologetics purposes—in fact cannot be used to build a scientific case for humans descending uniquely from an ancestral couple. Those who attempt to do so, like Craig (and Reasons to Believe, on whom Craig is depending) merely demonstrate that they do not understand population genetics.

Next, we’ll look at an additional problem for Craig’s model: the data that indicate that some present-day humans descend in part from non-human species such as Neanderthals.

Neanderthals and the Historical Adam: A Big Problem

In the last section, we finished our discussion of William Lane Craig’s incorrect use of an experimental population genetics study in his attempt to build a scientific case that all humans descend uniquely from Adam and Eve. Craig’s claims were made in the context of an apologetics class, and in the ensuing question and answer period a perceptive member of the audience asks Craig how species closely related to humans, such as Neanderthals, fit into the picture:

Question: I have heard Fuz Rana talk about on some of the Reasons to Believe podcasts that there is evidence for human Neanderthal interbreeding. I was wondering what that would do for the genetic diversity.

Craig: I wasn’t going to talk about that but that is a very, very unsettling question. When we talk about this human lineage, this includes not just modern human beings but that includes these other—I am hesitant to call them humans—but it includes these other organisms like Neanderthal man, there is this other group called Denisovans, and then of course earlier forms like Homo erectus and Homo habilis. These are all in the human line as well. So the question is: where do you want to insert Adam and Eve?

The challenge, as Craig sees it, is this: if Neanderthals are fully human, then they descend from Adam and Eve. The problem with this option, however, is that Neanderthals are present in the fossil record stretching back 300,000 years or more, far further back in time than his preferred date for Adam and Eve, which he places at about 150,000 years ago, where some studies indicate a population bottleneck. This is also further back in time than even the earliest Homo sapiens fossils, which are about 200,000 years old. If Neanderthals are a separate species, however—meaning they are not descended from Adam and Eve in Craig’s thinking—then the evidence for human-Neanderthal interbreeding is a problem, because humans are then interbreeding with a non-human species:

Craig: But apparently modern human beings interbred with Neanderthals as you say. I remember being taken aback when one of these population geneticists said to me when I was in Canada earlier this year that you, yourself, carry Neanderthal DNA. In my own genetic profile, I carry the DNA of these Neanderthals who interbred with human beings. Now, if they weren’t humans that meant that the descendants of Adam were literally committing bestiality, right? They were interbreeding with animals. Well, maybe that is possible. Maybe that is part of the fall of man into sin—that they engaged in behavior like that…

Certainly, Neanderthals create an issue for Craig’s apologetic. If indeed Neanderthals are human, then their genetic variation also needs to be accounted for in Craig’s model. This would add even more genetic variation to the human population, even more than standard evolutionary biology would need to account for. As such, Craig’s efforts to explain away the variation within present-day humans would also need to be expanded to include all Neanderthals, not just those that interbred with humans. The alternative option—that of bestiality that nonetheless produces viable offspring whose descendants are with us to the present day, myself and Craig included—is fraught with theological issues. Did the first generation of hybrid individuals have the image of God in Craig’s view? Were they subject to original sin, which Craig thinks is biologically inherited from Adam in some sense? Solving the Neanderthal problem in this way is no easy out—and it’s not surprising that Craig has not settled on an answer to this thorny question.

Census size and effective population size

Despite these obvious problems, there is another problem lurking under the surface related to these issues that Craig is seemingly not aware of: the difference between census size (the actual number of individuals in a population) and effective population size (the number that population genetics techniques estimate). Effective population size is the minimum population size needed, on average, to account for the amount of genetic variation we observe in the present—but census size is the actual population size that existed over time. Here’s the issue: census size is almost always larger than effective population size—substantially larger. For example: consider all the individuals in a population that do not reproduce—these individuals are part of the census size, but not part of the effective population size, since they did not contribute to the genetic variation seen in the present day. Or consider the case of close relatives that inherit the same genetic variation from their parents. Such “duplicate” individuals would not be included in the effective population size, but are part of the census size.

To return to Neanderthals, we know that most of them did not contribute their genetic variation to present-day human populations. Neanderthals, as a species, persist in the fossil record for at least 300,000 years—yet only a tiny fraction of human DNA in some present-day populations descends from them. This shows us that interbreeding between Neanderthals and humans was limited, and had only a small effect on present-day humans. If Craig were to accept that Neanderthals were indeed fully human, however, he would need to include all of them in the human census size, even though they have only a very minor contribution to the human effective population size. Even if Craig were to exclude Neanderthals, there are many humans in the past who have not left descendants to the present day—their lineages have died out. As such, they are part of the census size, but not the effective population size.

A concrete example of this was recently reported in the scientific literature. The study reported the sequenced genome of an ancient human male (named Oase 1, for the location where his remains were discovered) who lived about 40,000 years ago in Europe. His genome sequence is noteworthy because it contains very long stretches of DNA that are Neanderthal in origin—stretches that had not yet been broken up through crossing-over events, exactly like what we discussed previously. As such, this individual had a very recent Neanderthal ancestor—likely within 200 years of his birth.

A second finding, and the one relevant to our current discussion, was that Oase 1 did not contribute to present-day human populations—for any of his DNA. Even those regions of his genome that are “human” rather than “Neanderthal” were not transmitted to the present day. As such, Oase 1 is a concrete example of an individual who needs to be accounted for in the census size, even though we now know he is not accounted for in the effective population size. Even if Craig excludes Neanderthals as human, the problem doesn’t go away, because Oase 1 is a member of our species. If Craig does accept Neanderthals as human, then there is even more human genetic variation to account for.

So, the apologetic focus on the minimum effective human population size of 10,000 misses the point: the census size was larger than this. The 10,000 are merely those who have descendants in the present day, but they surely come from a population that was larger than 10,000, and likely much larger. As such, even if Craig’s attempts to minimize the effective population size were valid (and we have seen that they are not), they would not address the issue that the actual human census size at this time was larger.

References

William Lane Craig, Doctrine of Man (Part 11), Reasonable Faith, 2013.

Fazale Rana, Were They Real? The Scientific Case for Adam and Eve, Reasons to Believe, 2010.

Renaud Kaeuffer, David W Coltman, Jean-Louis Chapuis, Dominique Pontier, and Denis Réale. Unexpected heterozygosity in an island mouflon population founded by a single pair of individuals., Proc. Biol. Sci. 2007. https://dx.doi.org/10.1098/Frspb.2006.3743

S. Joshua Swamidass, Three Stories on Adam, Peaceful Science, 2018. https://doi.org/10.54739/3doe

S. Joshua Swamidass, BioLogos Deletes an Article, Peaceful Science, 2021. https://doi.org/10.54739/rv8k

Apr 23, 2022

Apr 25, 2022

Mar 6, 2026