In order to preserve the academic and historical record, this deleted article is published under Fair Use. All editorial comments are marked with a light gray background.

The article was first published by the BioLogos Foundation in 2015.

In 2017, this article was found to have several conclusion-altering scientific errors. January 2020, BioLogos briefly acknowledged errors in this article. However, they declined our request to transparently correct the scientific errors here. Instead, in June 2021, BioLogos deleted the article.

Poythress, chimpanzees, and DNA identity

In the previous article in this series, we’ve examined several of the converging lines of evidence that support the conclusion that our lineage became human as a population—one that has not numbered below about 10,000 individuals over the last 18 million years or more. Not surprisingly, this conclusion is one that many Christians find difficult to accept, since it is commonly held that this scientific finding is incompatible with the Genesis narratives (though as we have discussed, there is good reason not to think so, given the limits of what science can say). As population genetics information and its implications for interpreting Genesis have become more widely known among evangelical Christians, some apologetically-minded organizations and scholars have attempted to cast doubt on these lines of evidence.

One such individual is the Rev. Dr. Vern S. Poythress, professor of New Testament Interpretation at Westminster Theological Seminary. In 2013 Poythress authored a lengthy article on human population genetics that has subsequently been adapted into a short book, Did Adam Exist?, in the series Christian Answers to Hard Questions. Here’s a short video of Dr. Poythress introducing Did Adam Exist?: Christian Answers to Hard Questions: Did Adam and Eve Exist?

In both the article and the book, Poythress argues against the ideas that humans and other forms of life share common ancestors, and that humans descend from a population, rather than a pair. Since Poythress is one of the few leading evangelical scholars to address these issues, and to do so from a scientific, rather than an exclusively theological perspective, we will take the time in this series to carefully examine his arguments.

Poythress’s two main scientific arguments can be summarized as follows:

Reports of human—chimpanzee DNA comparisons overstate the identity between our two genomes because they selectively focus on areas where high DNA identity is to be expected because of functional constraint. The true overall identity value is lower, and is difficult to explain if common ancestry is true.

Population genetics estimates of ancestral human population sizes can only report on long-term population size averages, and thus could not detect a bottleneck of two individuals.

These two arguments are not disconnected as they might seem at first glance. Poythress correctly understands that some methods used to measure human ancestral population sizes use the DNA of species closely related to humans (such as gorillas and chimpanzees) in their analyses. As such, for some methods—such as incomplete lineage sorting, as we have examined—knowing the correct pattern of species relatedness is important for the analysis.

From these arguments, Poythress concludes that what he sees as the “biblical view of human origins”—that Adam was created directly from dust, that Eve was created directly from his side, and that Adam and Eve are the sole genetic progenitors of the entire human race—remains scientifically credible. However, as we will see, these arguments do not hold up to scientific scrutiny. As such, Poythress does not have scientific support for his preferred interpretation of the Genesis narratives.

Common ancestry and human-chimpanzee DNA identity

Poythress’s first line of argument is to call into question the commonly-reported values for human-chimpanzee genome identity—values on the order of 96-99%, depending on how the analysis is done. As we heard in the video linked above, Poythress claims that these values are overinflated:

For instance, the percentages go down to something like 70% if you actually take all the DNA, and not just the part that codes into proteins… And what about the 30% that doesn’t agree? Well, that’s problematic of where did that come from? That’s an awful lot when you think about it, to be different, if indeed there is common ancestry.

In Did Adam Exist? the argument runs along similar lines (pp. 7-8):

If the comparison focuses only on substitutions within aligned protein-coding regions, the match is 99 percent. Indels constitute roughly a 3 percent difference in addition to the 1 percent for substitutions, leading to the figure of 96 percent offered by the NIH… But we have only begun. The 96 percent figure deals only with DNA regions for which an alignment or partially matching sequence can be found. It turns out that not all the regions of human DNA align with chimp DNA. A technical article in 2002 reported that 28 percent of the total DNA had to be excluded because of alignment problems, and that “for 7% of the chimpanzee sequences, no region with similarity could be detected in the human genome.

Even when there is alignment, the alignment with other primate DNA may be closer than the alignment with chimp DNA: “For about 23% of our genome, we share no immediate genetic ancestry with our closest living relative, the chimpanzee. This encompasses genes and exons to the same extent as intergenic regions.” The study in question analyzed similarities with orangutan, gorilla, and rhesus monkey, and found cases where human DNA aligns better with one of them than with chimpanzees.

At this point in the book, Poythress includes two questions for reflection, since the book is intended for use in small-group discussions:

What new issue have we discovered about the 96% “identical” genetic codes? How does this change the situation?

Does human DNA always align best with chimp DNA? How might this change your attitude to the first statistic given?

While the text of Did Adam Exist? left these questions somewhat open, the intent of the arguments (and the questions themselves) seems clear when considered alongside Poythress’s summary statement in the video above. Poythress is advancing an argument that the overall DNA identity between humans and chimpanzees is much less than the commonly-agreed value of 96-99%. His view, it would appear, is that around 30% of our genome has no similarity to chimpanzees—lowering the overall identity value to about 70%.

This is of course, mistaken—but it will take some effort to explain exactly why this is the case.

It’s also not exactly clear what the basis is for the argument—is it the 28% that had “alignment problems” in the 2002 study? The 7% in that same study that had “no region of similarity” to match to? The 23% of our genome that “share(s) no immediate genetic ancestry with … the chimpanzee”? While Poythress does not divulge exactly how he is calculating the ~30% dissimilar figure, these are the only sources he cites to this end. As such, it appears that he views these statements as the technical support for his argument.

These scientific statements—while accurate—do not support the conclusion that the human and chimpanzee genomes are only 70% identical, however. We will begin to unpack why this is the case next.

How Close are Chimp and Human Genomes?

So far, we have begun to explore the arguments of Dr. Vern Poythress in his recent book Did Adam Exist?—specifically, his argument claiming that the true level of identity between the human and chimpanzee genome is on the order of 70%, rather than 96-99%. The first source that Poythress cites in support of his claim is a 2002 study comparing human and chimpanzee sequences:

The 96 percent figure deals only with DNA regions for which an alignment or partially matching sequence can be found. It turns out that not all the regions of human DNA align with chimp DNA. A technical article in 2002 reported that 28 percent of the total DNA had to be excluded because of alignment problems, and that “for 7% of the chimpanzee sequences, no region with similarity could be detected in the human genome.”

There are several problems here that would not, unfortunately, be apparent to Poythress’s intended audience. These problems, however, are immediately apparent to a geneticist. The first issue is that this paper, published as it was in 2002, cannot be a study comparing the entire human genome with the entire chimpanzee genome. In 2002, only a preliminary draft of the human genome was available (an improved version would be released in 2004). Moreover, chimpanzee genomics was in its infancy in 2002. Consulting the paper itself reveals that the sample size was a tiny fraction of the chimpanzee genome. The first line of the paper’s abstract indicates that the analysis was restricted to a small amount of DNA:

A total of 8,859 DNA sequences encompassing approximately 1.9 million base pairs of the chimpanzee genome were sequenced and compared to corresponding human DNA sequences.

Given that the human and chimpanzee genomes are about 3 billion base pairs long, this paper is describing the results for comparing approximately 0.06% of the two genomes. This 0.06% sample was drawn out of a larger sample of about 3 million base pairs, as the authors describe:

Twenty-eight percent of the total amount of sequence was excluded from the analysis, since the entire sequence, or parts of it, displayed more than one match in the human genome that was not due to known families of repeated sequences. For 7% of the chimpanzee sequences, no region with similarity could be detected in the human genome.

This is the section that Poythress is discussing when he states that “28 percent of the total DNA had to be excluded because of alignment problems”. First, note that the “total DNA” here is the 3 million DNA base pairs of the sample under study, not the total 3 billion DNA base pairs of the entire chimpanzee genome. Second, note that the reason for excluding the sequence from the analysis is not because it does not match the human genome, but because it matches it in more than one location. Genomes have a lot of repetitive DNA, and this is part of the challenge when comparing genomes.

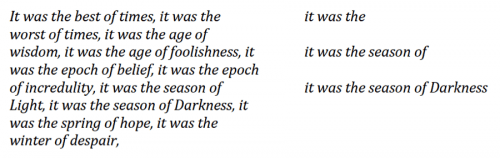

Perhaps a short aside about how genomes are sequenced would be helpful here. An analogy I have used before is to imagine a genome as a long text. The way scientists “read” a text (genome) is by chopping it up into fragments, reading the fragments, and then reconstructing the text by finding where the fragments overlap. This process works well until one encounters repeated text. For example, consider the opening lines of A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens:

As I have written before on this topic, we can reassemble a text with repetitive sequence if we use fragments that are long enough:

If we were to break multiple copies of the original paragraph into random short fragments of a few words each, we could in principle reassemble the entire piece from overlapping segments in the fragments. Where we would run into problems, however, would be with short fragments that are repeated. For example, if we had a fragment that read “it was the” we could not be sure where to place it, since it could match any one of nine locations. The only way to resolve this is to find larger fragments, such as “it was the season of”—which now matches one of only two locations. Better still would be “it was the season of Darkness” which aligns uniquely to only one location.

What Poythress seems to be misunderstanding is that the reason for excluding 28% of the sequence in the 2002 study was because it was the genomic equivalent of an “it was the” sentence fragment. These chimpanzee sequence fragments match the human genome—and may even match it perfectly—but they match in many places. The 2002 study, as an early study, used very short DNA fragments for its analysis. The fact that 28% of those fragments matched more than one location in the human genome is not at all surprising, and is not at all an indication that 28% of the chimpanzee sample is completely unlike human DNA. And even if it were (which it is not) the sample in question is only about one thousandth of the size of the human and chimpanzee genomes—a mere 0.1% of the total genome size.

What then, of the 7% that the authors could not match to the human genome? Here Poythress might have found an argument, except that, once again, this is not 7% of the entire chimpanzee genome, but 7% of one thousandth of the chimpanzee genome. Moreover, since this analysis was performed in 2002—thirteen years ago—it was done using a draft of the human genome that is far, far inferior to what we have in the present day. As such, it is highly likely that many of the excluded sequences do in fact have a match in the human genome, but failed to find a match in the 2002 draft.

Of course, the way to approach this question is to look at larger data sets, and use the most recent data available. When one does so, one finds that the human and chimpanzee genomes are indeed about 95% identical, genome wide—data that Poythress does not discuss, or even mention.

(As an aside, attempts to minimize the identity between the human and chimpanzee genomes are common among Christians who deny evolution. I have written extensively on this topic in the past with respect to the Discovery Institute and Reasons to Believe, for example—and interested readers will find a much more thorough discussion in those sources. Interestingly, my friend and colleague Todd Wood—a Young-earth creationist (YEC)– also has expended significant effort to combat these misunderstandings among those holding to anti-evolutionary views. He wrote a seminal paper in the creationist literature on the topic in 2006, and has also strongly critiqued Reasons to Believe on these issues. I have found Todd’s scholarship entirely trustworthy and a fascinating read, given his YEC views.)

As such, Poythress’s argument that human and chimpanzee DNA is only about 70% identical has not yet found scientific support. In the next post in this series, we’ll examine his second line of argument—that a large percentage of human DNA is a better match to other great apes rather than to chimpanzees. Here too we will see that Poythress fails to understand the relevant science, and that the evidence does not support his conclusions.

The Historical Adam and Incomplete Lineage Sorting

So far in this article, we have been exploring the anti-evolutionary arguments of Dr. Vern Poythress in his brief book Did Adam Exist?—specifically, his arguments alleging that that the human and chimpanzee genomes are only 70% identical. As we have seen, this line of argumentation is intended to call human—chimpanzee common ancestry into question, in part because shared ancestry is used in some methods of estimating the ancestral population size of our lineage. Since Poythress intends to argue that human ancestral population genetics cannot establish that humans descend from a population, rather than a pair, attempting to undermine confidence in common ancestry is part of the overall thrust of the book.

As we have seen, the argument in Did Adam Exist? for ~70% identity is as follows (pp. 7-8):

If the comparison focuses only on substitutions within aligned protein-coding regions, the match is 99 percent. Indels constitute roughly a 3 percent difference in addition to the 1 percent for substitutions, leading to the figure of 96 percent offered by the NIH… But we have only begun. The 96 percent figure deals only with DNA regions for which an alignment or partially matching sequence can be found. It turns out that not all the regions of human DNA align with chimp DNA. A technical article in 2002 reported that 28 percent of the total DNA had to be excluded because of alignment problems, and that “for 7% of the chimpanzee sequences, no region with similarity could be detected in the human genome.

Even when there is alignment, the alignment with other primate DNA may be closer than the alignment with chimp DNA: “For about 23% of our genome, we share no immediate genetic ancestry with our closest living relative, the chimpanzee. This encompasses genes and exons to the same extent as intergenic regions.” The study in question analyzed similarities with orangutan, gorilla, and rhesus monkey, and found cases where human DNA aligns better with one of them than with chimpanzees.

We have already dealt with the first section of the argument, and showed that the 2002 paper Poythress cites cannot bear the weight of his claims for it. Accordingly, we now turn to the second section of the argument—but as we shall see, it too fails to establish what Poythress claims for it.

The main thrust of the argument here seems to be that if a sizeable portion of our genome more closely matches a species other than chimpanzee, then a sizeable portion of our genome is not all that similar to the chimpanzee genome. This is an incorrect assumption, but it will take some effort to understand why.

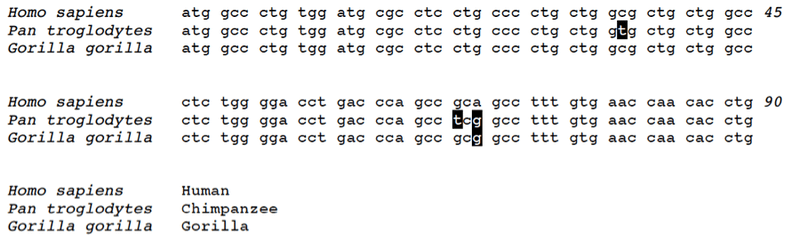

Perhaps the best way to appreciate how this works is to look at actual DNA sequences. Shown below is a section of 90 bases of DNA from the human, chimpanzee and gorilla genomes:

There are a few things to notice here. First, all three sequences are highly identical to each other, with only a few differences. Second, the human and gorilla sequences are the closest match to each other, with only one difference present. Third, the human and chimpanzee sequences have three differences. This pattern is representative for the sequence nearby as well, outside of what can be shown in a small figure. For a stretch of DNA in this area of the genome, the human and gorilla versions match more closely (98.5% identical) than do the human and chimpanzee versions (98.2% identical). As such, this genome region is part of the 23% of our genome that does not find its closest match in chimpanzees, but rather in gorillas.

The problem for Poythress’s argument should be immediately apparent. The fact that 23% of our genome matches the gorilla genome more closely does not imply that this very same DNA does not also match the chimpanzee genome with very high identity. In fact, this portion of our genome is highly identical to chimpanzees—it’s just that it’s slightly more identical to gorillas. The issue is that the human, chimpanzee and gorilla genomes are all highly identical to each other—but that for some portions of our genome, we are just a tiny bit more identical to gorillas than to chimps.

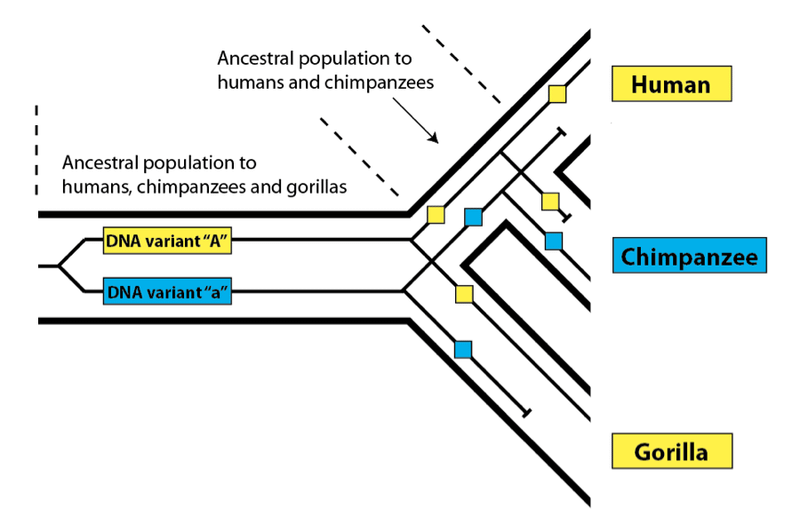

This observation, of course, raises the question of how this pattern arises between these three genomes. The answer, as it happens, is something we have already discussed in this series: incomplete lineage sorting. Since humans, chimpanzees, and gorillas are all descendants of a common ancestral population, we expect this phenomenon to occur, since not every DNA variant in the original population (i.e the one ancestral to all three descendant species) will sort down to all three modern-day species:

So, what Poythress sees as a problem for common ancestry does not, in fact, support his claim that large swaths of the human genome are dissimilar to the chimpanzee genome. Perhaps the confusion arose from failing to understand just how similar the genomes of humans, gorillas, and chimpanzees are—and that more closely matching gorillas is not at all an indication of dissimilarity with chimpanzees. The pattern produced by incomplete lineage sorting is (ironically enough) predicted by common ancestry—shared ancestry between three species. So, far from being a problem for common ancestry, this pattern is genome-wide evidence for common ancestry.

Having dealt with the human—chimpanzee identity issue, Poythress then shifts his focus to population genetics. His intent is to argue that the evidence we have discussed in this series is unable to conclusively assert that our species descends from a population, rather than a pair. As we will see next, however, this claim is similarly bereft of scientific support.

Population Genomics and Locating the Historical Adam

We now turn to his arguments against the conclusion of human population genetics that our species does not descend uniquely from an ancestral pair. Before we do, it’s worth noting, in passing, that Poythress’s arguments do not even attempt to refute the most obvious and straightforward evidence for common ancestry. For example, we see mutations in genes that form nested hierarchies in the human, chimpanzee, gorilla, and orangutan genomes. By far and away the simplest reason for this pattern is common ancestry, and as it turns out it’s the exact same pattern of common ancestry predicted by DNA sequence identity between these primates. We also see the remains of a gene in the human genome devoted to large-scale egg yolk production—something placental mammals such as humans simply do not need. If Poythress is to build a convincing case against human common ancestry with primates, these and other similar lines of evidence are the issues to tackle. As it stands, he has not even attempted to address them.

Having dealt with common ancestry to his satisfaction, Poythress then shifts to discussing human population genetics. As I see it, the three main arguments Poythress puts forward in this area are as follows:

Population genomics methods report only long-term average population sizes. These methods could not detect a bottleneck to two individuals, even if one existed, since they report only long-term averages.

Population genomics methods report sizes for more recent human populations, and do not address more distant history. As such, Adam and Eve may have lived further back in time than these analyses measure. This view is consistent with Scripture since the biblical genealogies may have gaps.

The findings of population genomics are based on uniformitarian assumptions that may not in fact be true if allowance is made for miracles.

While the third argument requires us to delve into the philosophy of science and how science might interact with theology, the first two claims are strictly scientific. As we will see, these scientific claims—like Poythress’s claims relevant to common ancestry—also fail to stand up under scrutiny.

Population bottlenecks and genetic variability over time

Poythress’s first claim, that population size estimates are long-term averages only and thus could not detect an original pair, appears a few times in the book:

Another paper uses genetic diversity among humans today to estimate average population size over the remote past, and offers nine different estimates in the region of 10,000. But these numbers depend on models that assume a constant population size through many generations. The figures are in fact giving us rough averages over long periods of time, so they say nothing about the possibility of two original individuals.

…the analysis always results in figures that represent a rough average over many generations in the human population. Consequently, the principal figures, like 3,100 for non-African populations and 7,500 for the African population, represent average populations over many generations. They say nothing one way or the other about whether the size decreased rapidly to two individuals in the more distant past.

This argument fails to understand how genetics works within a population. A population bottleneck to two individuals (the most extreme bottleneck that a mammalian population can experience) would not merely affect one or two generations, nor even a few hundred generations, but rather mark the genome of a species for hundreds of thousands of years. As such, it would easily be detected by modern population genomics methods. Let’s examine how such an event would shape genetic variability in a species.

The first effect an extreme bottleneck would have would be to greatly reduce genetic variability—the number of alleles that the species in question would possess. Recall that an allele is an alternative version of a DNA sequence. In mammals, each member of the species can have a maximum of only two DNA variants for any given DNA sequence—one allele inherited from mom, and one from dad. For a population to maintain high genetic diversity, you need a large number of individuals that have alternative DNA sequences to reproduce. If a population is reduced to only two individuals (or, as Poythress argues, was specially created starting with only two individuals) then the maximum possible DNA variation for any location in the genome is only four different alleles (two each in the male and female, with all four alleles being different from the others). Also, all alleles in this species genomes would coalesce to approximately the same time point, since all genetic diversity above this baseline (that would later accumulate through mutations) would be effectively the same age. However, as we have seen, humans are highly diverse genetically, and our alleles do not uniformly coalesce to a specific point in our history, but rather to a wide range of times, consistent with our lineage maintaining a large population over time.

A second effect of a reduction to (or start from) two individuals would be to place the original alleles into four chromosomal linkage patterns. These linkage patterns would slowly be broken up by recombination over successive generations. As with allele coalescence, we would see a pattern in present-day genomes that could be tracked back to four ancestral linkage patterns indicative of two original ancestors. These patterns in the human genome, however, indicate thousands of ancestors, as we have seen.

(Now it is of course possible—to jump ahead to Poythress’s third argument—to state that the patterns we see in the present-day human genome are the results of God’s miraculous intervention superimposed on what is in fact descent from an ancestral pair. I will address this possibility in a future post, but for now I’ll merely state that I do not find this argument plausible.)

So, if indeed humans descended from two individuals we would expect our present-day genetic diversity to be low, and the pattern of diversity to reflect an origin from a maximum of four original chromosomal arrangements. We do not, however, observe anything like this for present-day human genetic diversity.

Perhaps one way to appreciate that population genetics methods can (and do) detect extreme population bottlenecks would be to examine other mammalian species that do have the features we would expect for such an event. Cheetahs are one well-known example of a species with greatly reduced genetic diversity. Population genetics models for cheetahs support the hypothesis that they experienced a strong population bottleneck, which has recently been estimated at about 42,000—67,000 years ago, nearly eliminating their genetic variability. This signature remains with them to this day, since there has not been adequate time for new variation to arise through mutation. A second example would be the more recent bottleneck in Hawaiian monk seals that occurred in the 1800s, which is easily (and dramatically) seen in their extreme lack of present-day genetic variability. So, contrary to Poythress’s claim, the methods of population genetics are fully capable of detecting a reduction to (or start from) two individuals, since such an event would shape the genetic variability of that species for a very long time, well within the detection limit of current methods. The fact that our genome does not show these features thus remains a problem for his argument.

Next, we’ll discuss Poythress’s second claim—that perhaps Adam and Eve lived long ago enough to avoid detection by current methods.

Can Genetic Science Find Adam and Eve?

As we have seen, Poythress’s arguments are threefold:

Population genomics methods report only long-term average population sizes. These methods could not detect a bottleneck to two individuals, even if one existed, since they report only long-term averages.

Population genomics methods report sizes for more recent human populations, and do not address more distant history. As such, Adam and Eve may have lived further back in time than these analyses measure. This view is consistent with Scripture since the biblical genealogies may have gaps.

The findings of population genomics are based on uniformitarian assumptions that may not in fact be true if allowance is made for miracles.

Having dealt with the first claim, and shown it to be unrealistic in light of how a population bottleneck would shape the genetic variation of a species, we can now turn to the second claim: that perhaps Adam and Eve lived deep in the past, beyond the ability of current population genetics methods to reliably assess.

There are at least two significant problems with this approach. The first is that population genetics techniques are perfectly capable of estimating human ancestral population sizes over a wide range of times in the deep past, and the results do not support Poythress’s claim of an ancestral pair deeper in prehistory. Secondly, the further back in time one attempts to place Adam and Eve, the greater the tension one must be willing to bear between the internal evidence from Genesis about their time and setting, and what we observe in the paleontological / archaeological record. We will discuss these problems in turn.

Population genetics and human prehistory

In the section of Did Adam Exist? Where Poythress discusses ancestral human population sizes, he is primarily interacting with my 2010 paper in Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith (PDF) that discusses the evidence for human population genetics and common ancestry. One study that I discuss in that paper uses linkage disequilibrium to estimate human ancestral population sizes between about 20,000 and 100,000 years ago, but deliberately excludes dealing with genetic variation that would estimate population sizes in the more distant past. Poythress notes this limitation, and uses it to frame an argument that perhaps Adam and Eve lived before this time:

the study indicates that there is an effective limitation to how far one can probe into the past. Information based on correlations between nearer locations on a chromosome probes further into the past, but the analysis always results in figures that represent a rough average over many generations in the human population. Consequently, the principal figures, like 3,100 for non-African populations and 7,500 for the African population, represent average populations over many generations. They say nothing one way or the other about whether the size decreased rapidly to two individuals in the more distant past.

Later in the book, Poythress makes a case that the Genesis genealogies do not exclude such a possibility:

William Henry Green did an extensive analysis of biblical genealogies and concluded that they may contain gaps. If they do, the gaps mean that we cannot use Ussher’s procedure of adding up the years in the genealogies to obtain a date for the creation of Adam and Eve. The Bible simply does not tell us how long ago it was. Thus, Adam and Eve may have lived further back in time.

Taken together, Poythress leaves the impression that human population genetics models cannot reach back far enough in time to locate Adam—and that locating Adam and Eve as our unique ancestors deep in human prehistory is compatible with the Genesis narratives.

The first problem with this argument is based on the same misunderstanding that we discussed in the last part. As we saw, a population bottleneck to two individuals will markedly affect the genetic variability of a species for tens of thousands of years or more. Here Poythress notes that one particular study reaches back to 100,000 years, and hypothesizes that Adam and Eve perhaps lie beyond that limit. If they did so, however, they would have to be tens of thousands of years removed from that limit in order for the data at 100,000 years to appear as it does (barring, of course, recourse to miracles).

Secondly, noticing that one study reaches back to 100,000 years is not the same as establishing that population genetics as a field cannot reach back further. Indeed, as more and more human genetic variation data becomes available, we are able to look at various time points in our prehistory with increasing accuracy. For example, one such study published in 2011 uses coalescence methods to estimate the population size of our lineage between 10,000 and 1,000,000 years ago. The results are in good agreement with prior estimates: back to 1,000,000 years ago, our population has never numbered below about 10,000 individuals. In fact, as one goes further back in time, our population size increases: the bottleneck to 10,000 between 40,000 and 60,000 years ago is the smallest population for our lineage over the past million years. Recently a very similar approach was applied to a larger data set, with the same results. While Poythress could not have read the more recent paper prior to writing, the 2011 paper was available for over a year before he wrote the text of Did Adam Exist? and published it in the Westminster Theological Journal. Contrary to the impression he gives his readers, human population genetics had already examined the time he implied was unknowable, and demonstrated that no bottleneck occurred in our lineage between 100,000 and 1,000,000 years ago.

Adam and his Genesis context

Aside from the population genetics data that span our prehistory back to one million years, there are significant biblical challenges with locating Adam prior to 100,000 years ago. Briefly stated, the Genesis narratives assume a cultural setting consistent with the late Neolithic period, with agriculture and animal husbandry present (and metalworking a mere few generations off). To push Adam back to 100,000 years ago or more is to place him at a time where there is no archeological evidence for domesticated plants or animals, and only possible hints of artistic expression or religious activity. What Poythress might make of these difficulties is left unsaid.

Next, we’ll address Poythress’s third line of argumentation: that the uniformitarian assumptions of population genetics may in fact be incorrect due to miraculous events in our past.

Miracles vs. Genetics?

When the RMS Titanic sank in April of 1912, the tragic circumstances of one family made headlines. Canadians Hudson and Bess Allison, along with their two-year-old daughter Loraine, infant son Trevor, and various servants, were first class passengers—and as such Bess and the children had ready access to the lifeboats. In the chaos, however, things went awry: Trevor was borne to safety in a lifeboat by his nurse, likely with Hudson and Bess unaware. While it is not certain, it is likely that Bess and Loraine remained with Hudson in the ensuing search for Trevor until it was too late: Hudson, Bess and Loraine went down with the ship, and only Hudson’s body was recovered. Bess was one of only a handful of women in first class to perish; Loraine was the only child in first or second class to do so, leaving her infant brother as the sole surviving member of the family. Tragically, he too would die at the age of eighteen, leaving the sizeable Allison estate to more distant relatives.

In 1940, however, an American woman named Helen Loraine Kramer came forward claiming to be the long lost Loraine Allison, and heir to the Allison family wealth. Her claims were rejected by the Allison family, and after a time she dropped out of the media limelight. It was not until 2012, the 100-year anniversary of the sinking, that Kramer’s claims would again surface—this time championed by her granddaughter, who also was seeking interviews and a book deal. In 2012 there was, of course an easy way to determine the truth of the matter that had not been available in 1940: DNA evidence. Since the claim involved a continuous line of female descent, mitochondrial DNA evidence was relevant. Though Kramer’s granddaughter did not submit a DNA sample, another female relative of Kramer was willing. A female relative of Bess Allison also provided a sample, keen to finally put the trying ordeal to rest. The resulting analysis demonstrated that Kramer’s mitochondrial DNA was not at all a match to that of Bess Allison, indicating that Kramer cannot be Loraine Allison. The case is thus closed, though Kramer’s granddaughter still maintains a website where she attempts to cast doubt on the results and promises forthcoming evidence in her favor [Editor’s note: the website appears to have been taken down since this post was published].

We have been examining the arguments of Vern Poythress in his short book Did Adam Exist?—a book written to persuade Evangelicals that holding to a literal Adam and Eve as the specially created, sole genetic progenitors of the entire human race remains a credible option for Christian apologetics. As we have seen, Poythress’ scientific arguments have not withstood scrutiny. His final argument, however, is not scientific but rather theological in nature: that Christians should withhold judgment on human genetics because God may have employed miracles when creating the human race.

The argument in Did Adam Exist? takes the following form:

Now consider the second issue, the issue of gradualism. According to the picture in the Bible, God can work as he wishes. Many times he works through gradual processes, as we have observed. The regularity of these processes reflects God’s faithfulness. But he is not a prisoner underneath these processes. His rule over the world is what establishes the processes in the first place. He is free to work exceptionally, whenever he wishes. The experimental aspect of science is possible because of the regularities in God’s rule. But, rightly understood, science is subject to God and cannot presume to dictate to him what he has to do. It cannot forbid exceptions. Thus, exceptions are possible in the case of one-time, unrepeatable events, such as the origin of the universe, the origin of the first life, and the origin of human beings. The gradual processes that represent the usual means for God’s rule may have exceptions…

Matthew 1:18-25 and Luke 1:34-37 indicate that Jesus was born of a virgin. If a scientist had been able to test a sample of DNA from Jesus’ cells, would he have found a normal human Y chromosome, such as is present in the human DNA of men but not women? The Bible does not speak directly about such details, but Heb 2:14, 17; 4:15, and other passages indicate that Jesus was fully human. (Other passages, of course, indicate that he is also fully divine. He is one person with two natures, a divine nature and a human nature. This is a great mystery.) It is reasonable to infer that Jesus’ full humanity extended even to details like the Y chromosome. If so, the Y chromosome is an example of a thorough-going DNA match that was not the product of ordinary mammalian reproductive processes…

Jesus’ virgin birth is clearly a most exceptional case, but it shows that we must reckon with more than one possible account for DNA matches.

How might this argument apply to questions of our origins? In raising the possibility of miracles, Poythress is effectively claiming that no conclusion of genetics is sure, because there may be, unknown to us, the exceptional acts of God at play that render the evidence unintelligible to the methods of science. Taken to its logical conclusion, this argument would establish that no conclusion of science as a whole is sure—because, as Poythress would surely agree, the exceptional acts of God are not limited to genetics, but could in principle apply to any area of the natural world.

It should go without saying that I find this a puzzling, weak argument. I find it puzzling, because I know that Poythress does treat certain conclusions of science as settled, such as the evidence for an old earth. If God is free to work exceptionally in genetics, surely he is also free in geology, radiometric dating, cosmology, dendrochronology, and other fields that attest to the age of the earth. Yet Poythress does not argue for exceptions here (at least, not that I know of). Why does Poythress not do so? Because there is an overall pattern of evidence within those disciplines that point to the same conclusion (the earth is old), and to argue otherwise requires one to postulate that God is performing exceptional acts in an ad hoc manner to maintain a charade. It is formally possible, yes, that the earth is actually young and that God miraculously arranged the evidence, repeatedly, in such a way to give it an appearance of age—just as it is formally possible that God engineered the genomes of billions of people to give the unmistakable impression that we descend from a population of thousands and, further back, share ancestors with other species. But why would he do so? What possible end could it serve? While the Incarnation presumably required Jesus to have a Y chromosome, the patterns of DNA variation we observe in humans are not necessary. Perhaps some miraculous engineering of variation underlying our immune system might be explicable, but the vast majority of human DNA variation has no biological relevance—we’d all be fine being much more similar to each other than we are. Genetic diseases aside, most genetic variants in humans are neutral in their effects.

Taken to its logical conclusion, Poythress’s argument means it is not appropriate for geneticists to settle paternity disputes, use DNA evidence to solve murders, seek causes or treatments for genetic diseases, or investigate 75-year-old cases of fraud—because there is no necessary reason to suppose that what we observe is in fact the result of God sustaining natural genetic processes. Surely Poythress would not accept an appeal to miracle to explain away DNA evidence in the courtroom, yet that is the equivalent (and more) of what he asks of geneticists in the service of his apologetic.

References

Vern S. Poythress, Did Adam Exist? 2014.

S. Joshua Swamidass, Three Stories on Adam, Peaceful Science, 2018. https://doi.org/10.54739/3doe

Deborah Haarsma, Truth Seeking in Science, BioLogos, 2020.

Apr 12, 2022

Apr 7, 2015

Feb 14, 2026